It’s a September day in 2022, and Christine Wu Nordahl is holding a crying baby boy inside the MIND Institute at the University of California, Davis. The baby’s older sister, a 4-year-old autistic girl, is there for a behavioral diagnostic assessment, and her mother is nearby, helping to keep her calm and quiet. Nordahl’s lab assistant was supposed to watch the baby during the assessment, but he doesn’t know all that much about babies, especially crying ones. Nordahl, sensing an impending crisis, grabs the child and tells the lab assistant to pull up some baby videos and hand over his phone.

And that’s how Nordahl ended up sitting on the floor entertaining someone else’s baby for 90 minutes. “You do what it takes to get good data,” Nordahl says.

Nordahl first joined the MIND Institute, a research and care center focused on autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions, as a postdoctoral researcher in 2004. Back then, young children or those with limited communication abilities were usually sedated during scans or excluded from imaging work entirely. Her adviser, David Amaral, tasked her with devising a way to include those children, without sedation. To do this, her people skills have proved to be every bit as important as her talent as a researcher.

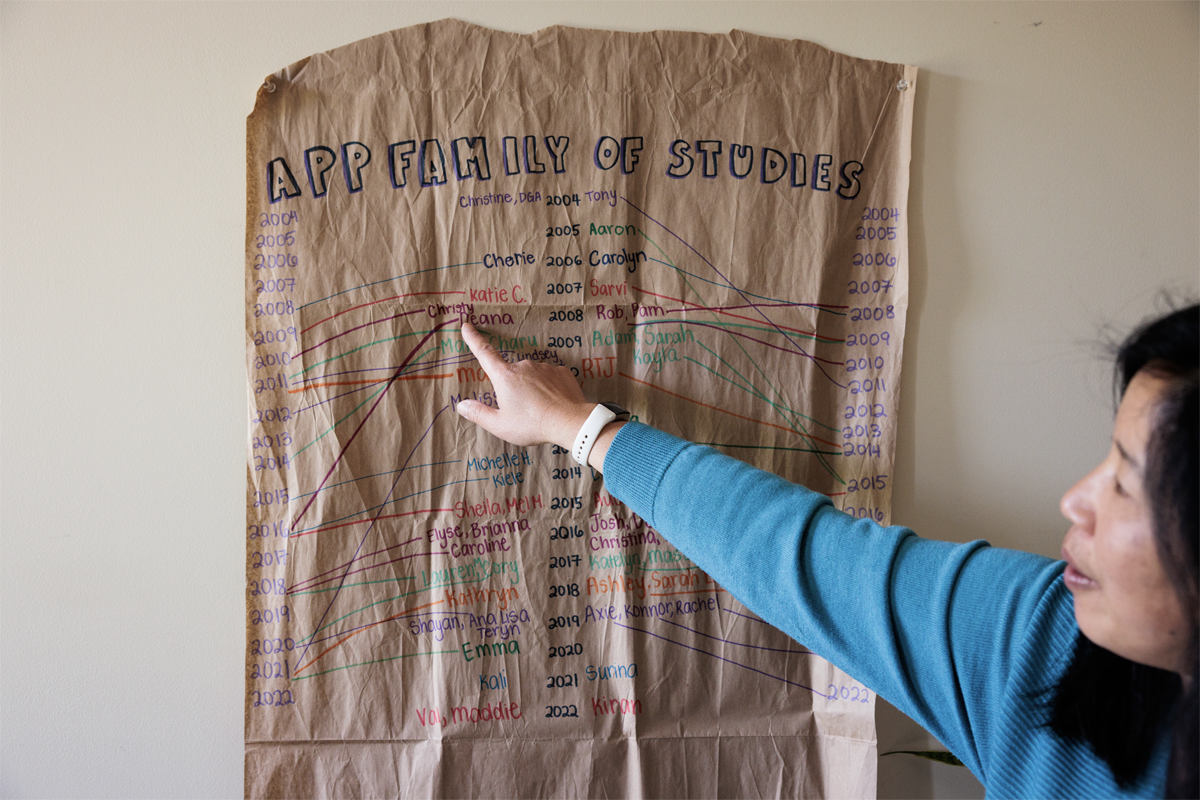

In the roughly 20 years since she joined, Nordahl has risen to become director of the Autism Phenome Project and, in August 2022, the Beneto Foundation Endowed Chair, which is endowed by one of the MIND Institute’s founding families. She has also amassed the largest longitudinal imaging study of autistic children in the world. “She has been a force for pretty dramatic change,” says MIND Institute director Len Abbeduto.

N

ordahl was born in University Park, Pennsylvania, in 1974, the second child and only daughter of Taiwanese immigrants who had independently moved to the United States to pursue graduate degrees and ended up at Pennsylvania State University. The family moved to Arnold, Maryland, a town of about 25,000 people, when Nordahl was 2.Nordahl grew up watching her parents navigate a culture and language that were not their own. She remembers, for example, when her mother once took her to the pediatrician and came home confused about the doctor’s request to see their kitchen chair — he had asked for a stool sample. Today Nordahl says she realizes her parents were, in a sense, doing what some autistic people do daily: masking behaviors in order to fit in. She knows it is not a direct comparison, but she sees similarities to her parents trying to figure out a world that isn’t “how you see it and how you’ve learned about it.”

The family had a piano, and Nordahl took lessons and competed through her teenage years. She was one of a handful of Asian students in her high school class. Her classmates were amicable and the teachers well intentioned, but there were still frequent reminders that she was an outsider. Partly in response to this, in high school she started a chapter of Amnesty International, to look out for others who needed help. But she found the demands of activism at odds with her own introversion. “I’m very conflict avoidant,” she says. “I don’t like to raise attention.”

She decided to study the brain in college. She applied to Binghamton University and Colgate University purely because she had heard upstate New York was pretty, adding Cornell University to the list only after a friend encouraged her to try for a higher-profile school. She was accepted there and signed up to major in neurobiology and behavior.