China’s growing awareness of treatments for autism

Helen McCabe’s analysis of autism interventions in China underscores the need to provide information on evidence-based treatments to parents and teachers.

In 1992, I was a student at the Hopkins-Nanjing Center in Nanjing, China. I wanted to volunteer with a child who had a disability, and was fortunate to meet a doctor who introduced me to a little girl with autism.

Each week, she and her parents would come to the center where I lived, so that I could play with her, provide an opportunity for socializing, and provide moral support to her parents while also learning from them.

Since then, serving as a volunteer, teacher-trainer and researcher, I have met hundreds of children with autism and their families and teachers in China.

Autism interventions in China have grown rapidly since then. Between 2002 and 2011, I conducted numerous interviews with parents and teachers of children with autism, as well as questionnaire-based research. These studies gave me the opportunity to talk in-depth to more than 200 parents and a similar number of autism professionals.

During this period, I also trained many hundreds of teachers and parents, in more than ten cities in China (including Nanjing, Beijing, Wuhu, Shenzhen, Changzhou, Lianyungang and Anshan).

Last year, I published a paper based on interviews with 13 Chinese teachers and other local experts, focusing on the growing awareness of autism in China and the impact of this awareness on interventions available there1.

There are many different autism interventions across the globe. In any society, it is essential to understand and use best practices based on evidence-based research. Yet, everywhere, there are also parents and teachers who seek to do as much as possible, as quickly as possible — despite the fact that evidence-based practices take a lot of time and intensive effort.

My analysis of the state of autism intervention in China points to the need for all of us to continue to focus on evidence-based practices. It especially emphasizes the need to provide that important information to parents and teachers, who are seeking to do their best for children with autism.

Old lessons:

In 1992, young teachers provided intervention for a few children with autism at a hospital in Nanjing. These teachers had backgrounds in early childhood education, but no understanding of autism.

The following year, a parent established the first private intervention organization, and the year after that, the hospital in Nanjing established a rehabilitation division specifically for children with autism.

Now, 20 years later, there are hundreds of “autism training organizations” (孤独症训练机构) across China run by parents, medical professionals, schools and others. But the quality of these organizations is shaped by the political and economic climate in China.

All training organizations are largely self-pay and most are focused on younger children. One teacher explained this bias towards young children from the point of view of the families who are willing to pay for the services: “I think if the child is still young, the parents think there is still hope, so they are willing to invest money. Because you must consider that all of these training and services require that parents pay, and this money doesn’t come from any social welfare program, but rather from parents’ income. So for families, if the child is already 17, 18 years old, will they still be willing to pay so much money and time to send their child to a training center?”

Instead, as children get older parents too often must make the choice to stop sending them for intervention in order to save money to plan for the future — which is uncertain in a society that has no government-run services for adults with disabilities.

Another challenge is that the growing demand for services has driven a field that is based on quantity, rather than quality, of services. Private and public organizations must compete with each other for students, and so they seek to be the best.

Yet, in a strangely contradictory way, a rush to provide services means less ability to focus on long-term systematic training of staff for truly effective practices. Instead, there is more focus on providing everything, including multiple methods and equipment that have unclear value.

One teacher said she and her colleagues focus on the latest international methods, such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), ‘structured teaching’ (the TEACCH method) and sensory integration training. They also rely on Relationship Development Intervention and Floortime, as well as communication training methods. “We combine structured teaching, ABA and sensory integration all together,” she told me. “We’ve combined all sorts of methods together.”

ABA, and in particular the method based on ABA known as discrete trial teaching, is an intensive one-on-one intervention often used with young children. It has gone through waves of popularity in China since 1998 and is currently seeing a new surge in interest. Hong Kong educators introduced TEACCH methods, such as structuring the environment and using visual schedules. These are quite popular in southern China.

Another professional explained that the trend to use multiple interventions is partly the result of parent demands.

“Parents [whose child has] just been diagnosed, they don’t have the ability to distinguish which organization is useful to their child. They just look at some methods online,” she told me. “If your program has everything, parents will think this gives their child more potential.”

However, there are promising developments as well. I talked to several people who used the term “survival of the fittest” and were optimistic that in the not-too-distant future, the effective programs that provide quality instruction to children and families would be the ones to survive.

A lot of autism organizations in China increasingly focus on teacher training, seeking training from both Chinese and foreign experts in autism. Efforts are being made to understand and implement evidence-based practices.

As with anything, funding is a major issue. With little to no government assistance for this education, it is no wonder that organizations have to focus on attracting paying students. They are unable to, for example, send teachersto attend intensive teacher-training programs that would better prepare them for their work.

This is because there is such a demand from families for intervention for their children that the organizations cannot afford to release a teacher for any period of time.

As one participant explained, “If you ask for more, the parents can’t afford it. If you charge and make less, the organization can’t survive.”

In September 2012, I met with Chinese government officials who are seeking to better understand the educational needs of children with autism. I urged them to consider advocating for and allowing all children to be included in the compulsory public education system. This is an essential step towards addressing the current challenges in the field of autism educational intervention in China.

Helen McCabe is project coordinator and inclusive education specialist at Perkins International in Watertown, Massachusetts.

References:

1: McCabe H. Autism Epub ahead of print (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

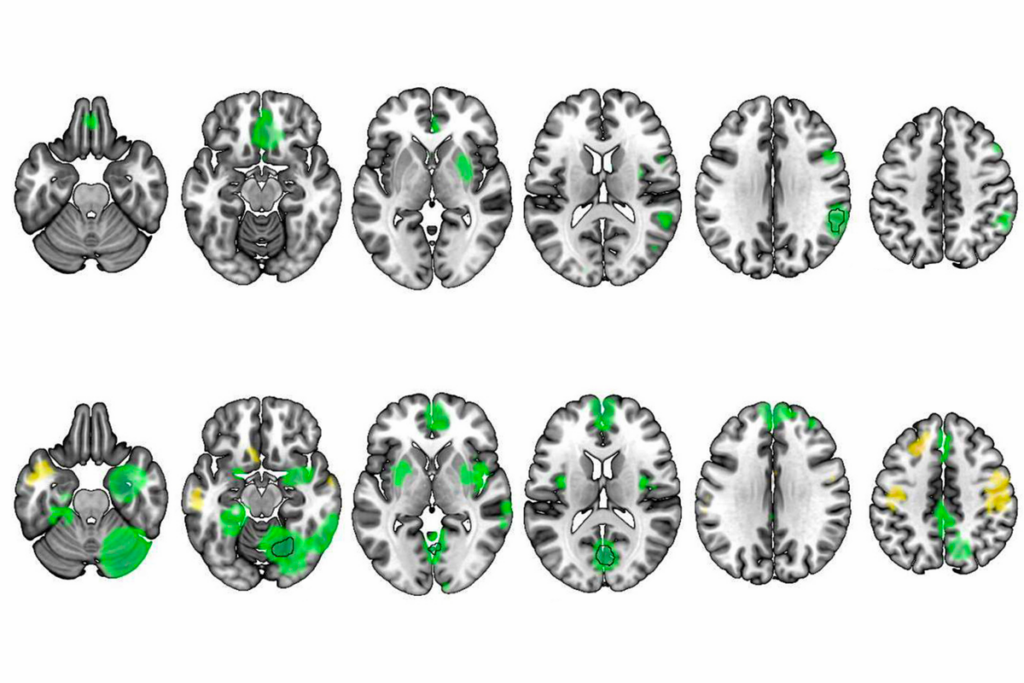

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

BCL11A-related intellectual developmental disorder; intervention dosage; gray-matter volume

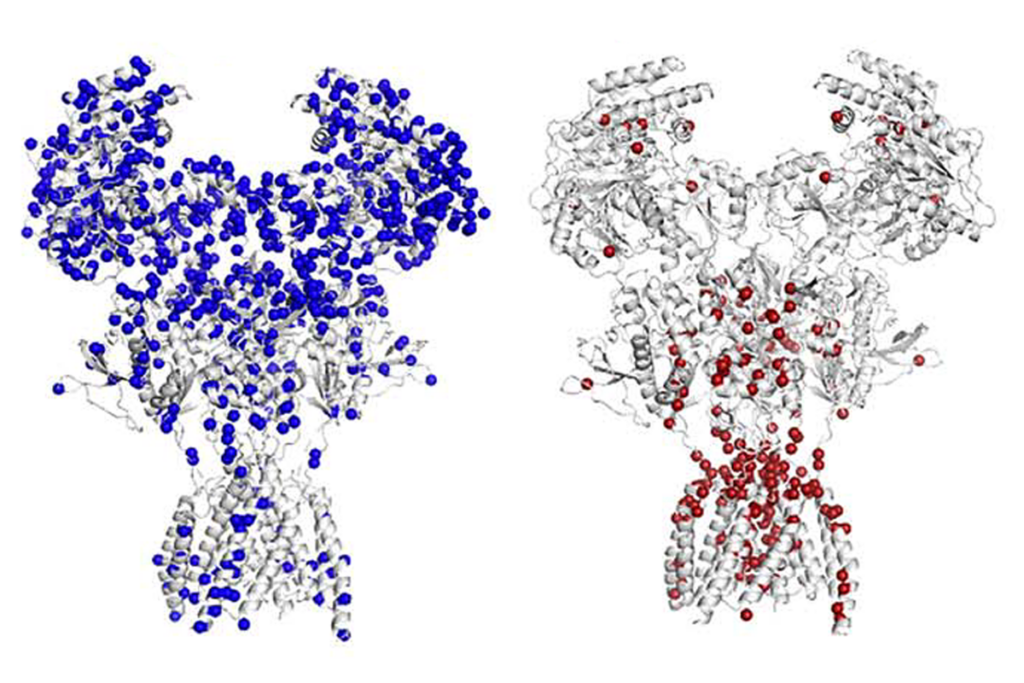

Emotional dysregulation; NMDA receptor variation; frank autism