Children with autism may forego behavioral therapy for meds

Many children with autism who take antipsychotic medications do not receive behavioral therapy.

Many children with autism who take antipsychotic medications do not receive behavioral therapy, according to a new study1. The findings suggest that these children start taking the drugs, many of which have harsh side effects, without first trying safer options.

“That’s a red flag,” says lead investigator Evdokia Anagnostou, senior clinician scientist at the Bloorview Research Institute in Toronto, Canada. “We should be using medications only when our behavioral approaches fail.”

Medications are not good long-term options because their benefits disappear when an individual stops taking them, the researchers say.

“The most important thing is to teach our kids skills that will allow them to learn how to regulate their own arousal level, emotions and behavior before we give medication,” Anagnostou says. “Medications do not teach skills; they’re Band-Aids.”

Doctors prescribe so-called ‘atypical’ antispsychotic drugs, such as aripiprazole, risperidone and ziprasidone, for irritability, aggression and other challenging behaviors in children with autism. The drugs often have side effects, such as weight gain, motor tics and an increased risk of diabetes.

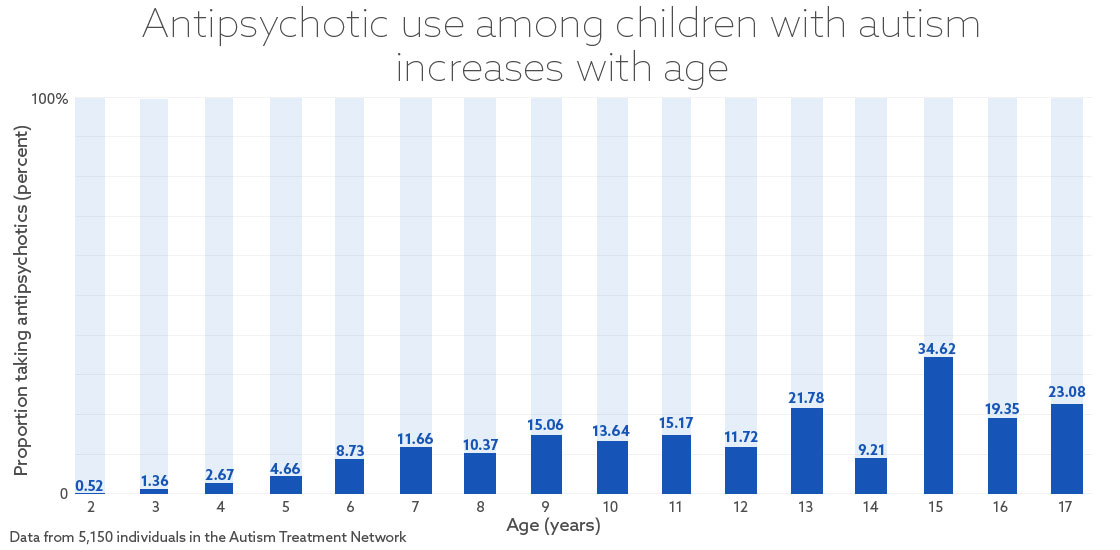

Anagnostou’s team reviewed medical records of 5,150 children and teenagers with autism. They also looked at each child’s age, gender, race and ethnicity, body mass index and geographic location. The participants are registered in the Autism Treatment Network, a group of 17 medical centers in the United States and Canada.

The study reveals that the proportion of children taking these drugs increases with age, a finding in line with those from previous studies (see graphic below). About 5 percent of 2- to 11-year-olds with autism take the drugs; the number rises to nearly 18 percent for children aged 12 to 17 years. The results appeared 16 February in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

Graphic by Nigel Hawtin

Replacement remedy:

The researchers also discovered that about one-third of each group taking the meds had not received any form of behavioral therapy in the month prior to enrolling in the network.

“Clinicians and families may be using medication in place of using behavioral therapies,” says Daniel Coury, medical director of the Autism Treatment Network, who was not involved in Anagnostou’s study.

Coury says some children in the study may not have access to behavioral therapies, perhaps because they live in remote areas, because their insurance does not cover it or because their families cannot afford the expense. “If we were able to get them those therapies, they may not need these medicines,” he says.

Anagnostou’s team also linked atypical antipsychotic use to gut and sleep problems, both of which are common among children with autism. Children taking the drugs also tend to be overweight or obese, non-white Hispanic and take multiple psychiatric drugs, such as stimulants for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or antidepressants.

References:

- Lake J.K. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025

Neuroscience’s leaders, legacies and rising stars of 2025