Changes in brain anatomy may reflect autism traits

Some traits of autism are associated with obvious differences in brain structure, and the scope of these alterations may depend on the person’s sex.

Some traits of autism are associated with obvious differences in brain structure, according to two new studies of same-sex twins. The scope of the alterations depends on the person’s sex, one of the studies suggests.

Girls with autism or autism traits show structural differences in 11 brain regions compared with an unaffected twin sister. In boys, autism traits are associated with differences in only two brain regions1.

The findings support the idea of a ‘female protective effect,’ which posits that girls are biologically protected from autism.

“The female protective effect says we [see] about the same phenotypic severity of autism despite seeing more neurological alterations, and that’s also what we find in our study,” says lead researcher Sven Bölte, professor of child and adolescent psychiatric science at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

Scientists have found isolated structural brain differences between autistic boys and girls. But by examining brain structure in same-sex twins, Bölte and his colleagues could control for genetics, age, sex and shared environmental factors.

Identical twins, who have virtually the same DNA, also show structural differences when one twin has autism, indicating that factors other than genetics shape brain anatomy, the researchers found. “There’s also room for environmental factors,” Bölte says.

A study of same-sex twins published in January shows that environmental factors such as trauma during birth can contribute to brain structure and, accordingly, behavior2. That study did not look at sex differences.

Bölte’s work is the first to match behavioral characteristics of each sex with brain-imaging data, says Meng-Chuan Lai, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved in the study.

“This is a unique one because they have the imaging measurements, so you can tap into the brain-behavior association within the twin-study design,” Lai says.

Regional matters:

Bölte and his colleagues recruited 74 same-sex twin pairs (31 female and 43 male) aged 9 to 23 years; 49 of these pairs are identical twins. The participants are all from the Roots of Autism and ADHD Twin Study in Sweden3.

The team evaluated the participants and diagnosed 11 females and 17 males with autism (including both twins in three pairs of each sex). Clinicians also measured autism traits using the Social Responsiveness Scale (SRS). The researchers then scanned the participants’ brains with magnetic resonance imaging.

The researchers matched the difference in SRS scores within each twin pair to differences in their brain volume and surface area, as well as the thickness of the cerebral cortex, the brain’s outer layer.

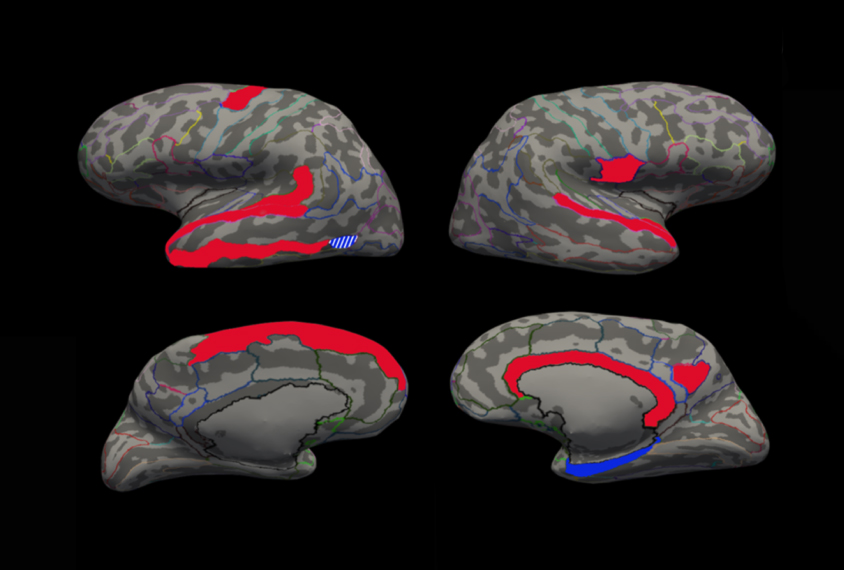

A girl who has more autism traits than her twin sister tends to have less volume and surface area than her sister in five brain regions, many of which are associated with social communication. The surface area of six other regions with sensory, language and other functions also tends to be smaller in the female twin with autism.

A boy who has more autism traits than his brother has more gray matter (made up of neuronal cell bodies) than his brother in one region and decreased thickness in another. Both regions are involved in high-level visual processing; neither showed differences in girl twins.

“What’s striking for me is it’s not that you [only] have more regions that are affected in the female brain, it’s also that it’s different regions,” says study investigator Élodie Cauvet, a postdoctoral fellow who works in Bölte’s lab.

The researchers found similar, but fewer, differences when they restricted their analysis to identical twins, who share the same genetic makeup. The research appeared in December in Cerebral Cortex.

Identical differences:

The work needs replication in a larger sample, but it is in line with the theory that the biological changes underlying autism features in boys are less extensive than they are in girls, says Christine Wu Nordahl, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, who was not involved in the research.

“It’s more evidence suggesting that sex really is important, and you should consider males and females differently,” she says.

The use of autism traits as a measure is also novel, and it may have led the researchers to include girls with autism who would otherwise have been missed because of bias during the diagnostic process, Nordahl says.

The January study also looked at the roots of brain structure in same-sex twins. The researchers scanned the brains of 82 twin pairs aged 6 to 15 years, including 78 children with autism. They used a statistical model to compute structural brain differences within pairs of identical and fraternal twins. They also explored brain differences between autistic and typical participants. The work was published in Molecular Psychiatry.

Brain structure is more similar overall among identical twins than among fraternal twins, suggesting that genetics has the biggest influence on brain anatomy in both autistic and typical individuals. But environmental variables affect two structural features — the thickness of the cerebral cortex and the volume of nerve fibers in the cerebellum — more in autistic children than in typical ones.

“This is bringing us closer to understanding the biology and this interface between genetic and environmental factors,” says lead researcher Antonio Hardan, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California.

Bölte says he plans to follow up with the twins in 5 or 10 years to see whether the correlations between autistic traits and brain structure remain at later ages.

References:

Recommended reading

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Who funds your basic neuroscience research? Help The Transmitter compile a list of funding sources

The future of neuroscience research at U.S. minority-serving institutions is in danger