Some genomic areas that help determine cerebellar size are associated with autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, according to a new study. But heritable genetic variants across the genome that also influence cerebellar size are not.

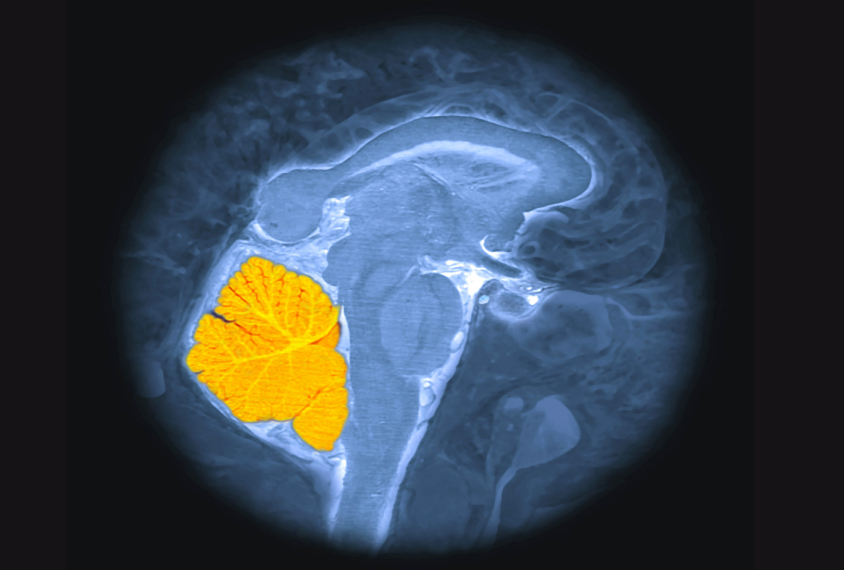

The cerebellum sits at the base of the skull, below and behind the much larger cerebrum. It coordinates movement and may also play roles in social cognition and autism, according to previous research.

The new work analyzed genetic information and structural brain scans from more than 33,000 people in the UK Biobank, a biomedical and genetic database of adults aged 40 to 69 living in the United Kingdom. A total of 33 genetic sequence variants, known as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), were associated with differences in cerebellar volume.

Only one SNP overlapped with those linked to autism, but the association should be explored further in other cohorts, says lead investigator Richard Anney, senior lecturer in bioinformatics at Cardiff University in Wales.

“There’s lots of caveats to say why it might be worth following up on,” Anney says. “But from this data alone, it’s not telling us there’s a major link between [autism] and cerebellar volume.”

So far, cognitive neuroscientists have largely ignored the cerebellum, says Jesse Gomez, assistant professor of neuroscience at Princeton University, who was not involved in the work. The new study represents a first step in better understanding genetic influences on the brain region and its role in neurodevelopmental conditions, he says.

“It’s a fun paper,” Gomez says. “It’s the beginning of what’s an exciting revolution in the field.”

O

f the 33 inherited variants Anney’s team found, 5 had not previously been significantly associated with cerebellar volume. They estimated that the 33 variants account for about 50 percent of the differences in cerebellar volume seen across participants.Anney and his team then compared their analysis with previous genome-wide association studies of SNPs linked to autism, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Of the 33 variants they flagged, 1 had previously been associated with autism, 5 with schizophrenia, 2 with bipolar disorder and 1 with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Overall, however, genetic variants associated with cerebellar volume were not significantly linked to any of those conditions.

The findings were published in Molecular Psychiatry in January.

The sample size is on the small side for a genome-wide association study, which calls some of the findings into question, says Tinca Polderman, associate professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Amsterdam UMC in the Netherlands, who was not involved in the work. Genetic correlations between cerebellum volume and other cerebral lobes were unusually low, for example, she says.

“I am not completely convinced by the results of this study,” Polderman wrote in an email to Spectrum, adding that replicating the results in a larger cohort would help.

And the analysis doesn’t rule out a role for the cerebellum in autism or other conditions, Gomez says. There could be many genetic factors that influence cerebellum function without affecting its overall volume, he says.

“I’m sure the cerebellum does play a role in lots of disorders. It’s heavily connected to the brain,” Gomez says. “The way you can analyze this dataset is potentially a little bit limited.”

Anney and his team plan to repeat the analysis in cohorts with different demographic characteristics from those in the UK Biobank, such as a group that includes children.