Career-prep program fosters strengths of teens with autism

In a new program based in New York City, autistic students work to build skills that cater to their strengths or special interests.

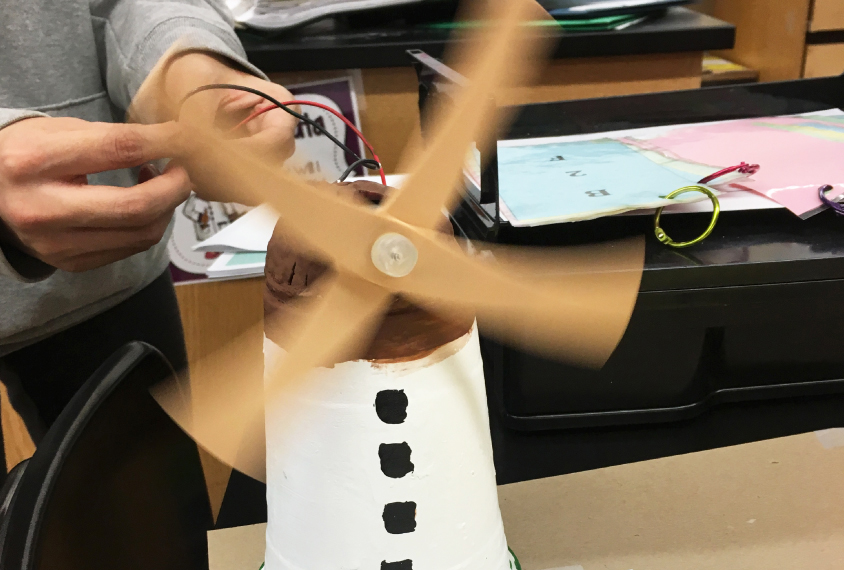

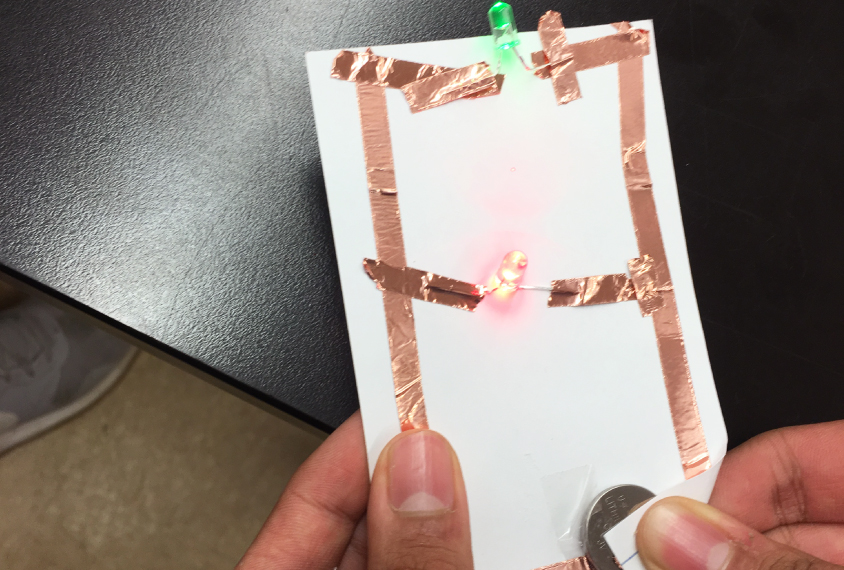

One Thursday afternoon in November, about a dozen students around age 13 huddle at tables in a cluttered science classroom. Some chat while they work, using copper tape and a watch battery to build a circuit that will power an LED bulb. Others are silent, engrossed in their project.

The students, mostly eighth graders at Public School 219 in Queens, New York, are part of a program for students with autism and their non-autistic peers. Launched in 2016 in three schools in New York City, its goal is to prepare students for their eventual career search.

Many adults with autism are underprepared for the workforce, so it’s critical to give students skills to make them competitive candidates later on, says Kristie Koenig, co-leader of the project and associate professor of occupational therapy at New York University.

The program, called IDEAS, for Inventing, Designing, and Engineering on the Autism Spectrum, is funded by a $1.1 million National Science Foundation grant. Now in its third year, it may soon be self-sustaining: Its leaders are working with an independent research center to assess its success and create a path for its expansion.

The program is particularly promising because it connects students with technology and skills they might use professionally, says David Mandell, director of the Center for Mental Health Policy and Services Research at the University of Pennsylvania. Mandell is not involved with the project.

Many programs for students with autism focus on filling in gaps in their knowledge or skills — say, in organization or social communication. In the IDEAS program, students work on projects that cater to their strengths or special interests. For example, if a student has an interest in anime, a style of Japanese animation, she might learn how to design an anime character on a computer and then to create a figurine of the character using a 3-D printer.

Some other community programs also focus on particular interests and building technical skills, says Connie Kasari, professor of human development and psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles. “But the [IDEAS students] are starting young, so that is exciting for those students able to access the curriculum,” she says. Kasari is not involved in IDEAS but has created other courses for autistic students.

Producing prototypes:

The program’s premise first came up in 2013. Wendy Martin, a research scientist at the Educational Development Center, a nonprofit organization headquartered in Waltham, Massachusetts, suggested the idea during a work retreat discussion about how students’ interests tend to drive hands-on projects.

Martin then brought the idea to Koenig, who leads ASD Nest, a large autism inclusion program that operates in 45 New York City public schools. Together, Martin and Koenig approached the New York Hall of Science, a science museum that runs similar programs, for help creating a curriculum.

The group applied for funding in 2013, but their bid was unsuccessful. After repeat attempts each year, they finally won funding in 2016 to launch the program as part of ASD Nest.

In the program’s first year, educators from the New York Hall of Science ran IDEAS, with help from classroom teachers and graduate students at New York University’s Tandon School of Engineering.

In year two, the museum pulled out as planned, and the graduate students and school teachers took over. Heading into the grant’s final year this September, IDEAS is designed to be entirely teacher-run.

This past academic year, the program included 25 students with autism and 24 typical students across the three schools. The schools can choose how to recruit students and which ages to include.

Lunch and learn:

Students in the program meet during lunch or after school at least once a week for 10 weeks each semester, learning maker skills such as woodworking, 3-D printing and laser cutting. The curriculum also includes basic engineering design principles: building a prototype, testing it, making changes and repeating the process until the prototype is functional.

Several weeks into the program, each student chooses a project to work on, based on his interests and the skills he has learned. For example, one student with an interest in World War II and European empires created a wooden game board shaped like a map of Europe and laser cut more than 150 game pieces. The student drafted a set of rules of play, and his classmates gathered to play the game.

Students also practice social and practical skills needed for success in a job. By collaborating with their peers on various projects, they learn communication and organizational skills, teamwork and the ability to cope with change.

“If they don’t have those skills to work in project-based learning, then they’re not going to do well in the job market,” Kasari says.

Because the students are comfortable with the projects’ focus, the program also boosts their confidence in social interactions.

“Schools unfortunately have a mandate that often ends with academic achievement, and for a lot of kids with autism, that’s not where they experience difficulty,” Mandell says.

Expansion plans:

All students in both IDEAS and ASD Nest can keep up with their peers academically. Kasari says she would like to see programs for autistic students with a broad range of abilities.

“Some of our minimally verbal kids would be just as interested in this topic as some of our highly verbal kids,” Kasari says.

The pilot grant that funds IDEAS ends in August 2019. Within the initial three schools, the program should be self-sustaining by then, Koenig says. She is applying for funds to expand the program to more schools, and to a broader age range. An independent nonprofit organization based in California called SRI International is set to assess the program’s impact and determine a process for expansion.

At the after-school program at Public School 219, one student narrates her strategy as she arranges strips of copper wire tape to create her LED circuit.

“I’m going to tape them down first, then cut them down, in case one is too large,” she says.

Another student suddenly becomes emotional and steps out into the hallway with a teacher. In a few minutes, he returns, rejoins his table, and gets back to work. Soon, it’s time to pack up, but he remains in his seat, absorbed in his project.

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

During decision-making, brain shows multiple distinct subtypes of activity

Basic pain research ‘is not working’: Q&A with Steven Prescott and Stéphanie Ratté