Cancer drug wards off seizures in mouse model of tuberous sclerosis

A drug called rapamycin prevents seizures in a mouse model of the autism-related condition tuberous sclerosis complex.

A drug called rapamycin prevents seizures in a mouse model of the autism-related condition tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). The drug also decreases the frequency of seizures in mice that begin taking it after the onset of the episodes.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings today at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

“You can give it before the seizures start and prevent the seizures. But it also works in a treatment mode,” says Steven Roberds, chief science officer at the Tuberous Sclerosis Alliance, who presented the work.

TSC is a genetic condition caused by mutations in one of two genes, TSC1 or TSC2. People with TSC often have benign tumors throughout their brain and body. About half have autism, and more than 80 percent develop epilepsy, which is characterized by seizures.

One of the main functions of both TSC1 and TSC2 is to put the brakes on a cellular growth pathway called the mammalian target of rapamycin, or mTOR. The drug rapamycin suppresses this pathway and has long been used to treat cancer. It is also in trials for treating TSC.

In the new work, the researchers used a mouse model of the condition that lacks TSC1 only in brain cells call astrocytes. These mice have previously been shown to have seizures1.

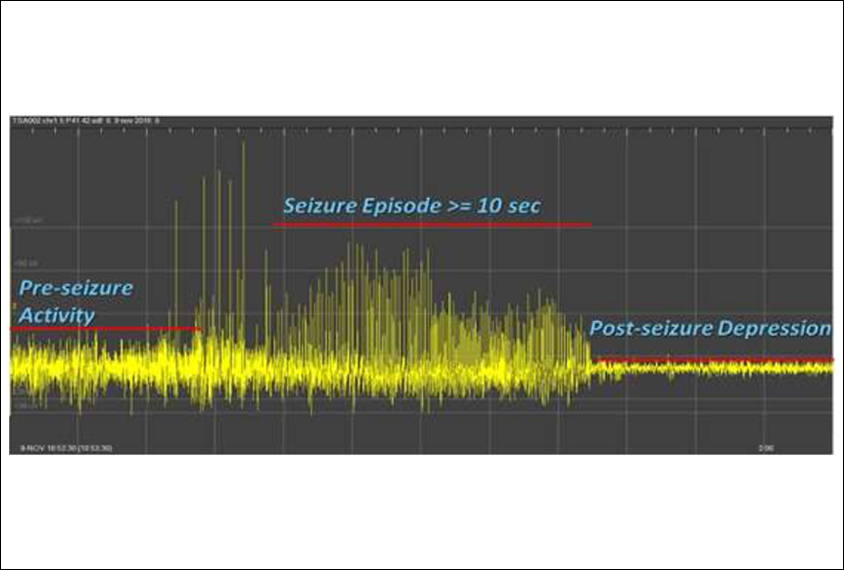

Seizure stopper:

When the pups were 21 days old — before the onset of seizures — the researchers gave them a daily dose of rapamycin. Another set of mice got a sham drug for 14 days and began having seizures; they received rapamycin starting at day 35. A third set of mice got only the sham drug.

The team measured the pups’ brain activity using electroencephalography. The mice treated with rapamycin starting at day 21 had no seizures. On average, the mice treated with rapamycin starting at day 35 had fewer than two seizures per week at 6 weeks of age and less than one seizure the following week. By contrast, mice that got only the sham drug had an average of 3.5 seizures at 6 weeks.

“Being able to treat with an mTOR inhibitor corrects many of the aspects,” Roberds says. “And the earlier you can do that, the better the outcomes, at least in mice.”

The researchers didn’t test whether mice have to get the drug by a certain age for it to prevent seizures.

Afinitor (everolimus), a rapamycin analog that is approved by the Food and Drug Administration for cancer, has proved effective for treating tumors in people with TSC. It is in clinical trials for treating seizures, Roberds says.

To determine whether Afinitor can prevent seizures in people, researchers need to test it in infants with TSC, he says. “That would be a real breakthrough in terms of being able to prevent the development of seizures.”

Roberds and his colleagues are enrolling babies with TSC in a trial of another drug that can prevent seizures.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

References:

- Uhlmann E.J. et al. Ann. Neurol. 52, 285-296 (2002) PubMed

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt