Cancer drug finds new use as treatment for Angelman syndrome

Compounds that mimic a cancer drug restore expression of the key gene mutated in Angelman syndrome, a condition related to autism.

Compounds that mimic a cancer drug restore expression of the key gene mutated in Angelman syndrome, a condition related to autism, according to a new study1. The drug was sidelined because of severe side effects, but the new compounds revive the approach.

Angelman syndrome is a genetic condition characterized by developmental delay, frequent seizures and problems with language. It stems from mutations in the maternal copy of the gene UBE3A. The paternal copy is typically silent, so mutations in the maternal copy result in the lack of functional protein.

The cancer drug topotecan and the new experimental compounds work by unsilencing the paternal copy.

“We’re excited because it’s yet another shot for treatments for Angelman,” says lead researcher Benjamin Philpot, professor of cell biology and physiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “But we need to very carefully determine whether we can safely get it delivered to the brain without adverse side effects and that it can produce long-lasting unsilencing.”

A second study hints that the approach might ease Angelman syndrome traits even in adults2.

“It continues to be an exciting time in Angelman syndrome research as we inch closer and closer to using the right drug at the right time,” says Lawrence Reiter, professor of neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis, who was not involved in either study.

Safer alternative:

Topotecan and the new compounds all work by blocking an enzyme called topoisomerase 1, which enables long segments of RNA to be expressed. An especially long piece of RNA silences paternal UBE3A, and preventing production of that piece unsilences UBE3A.

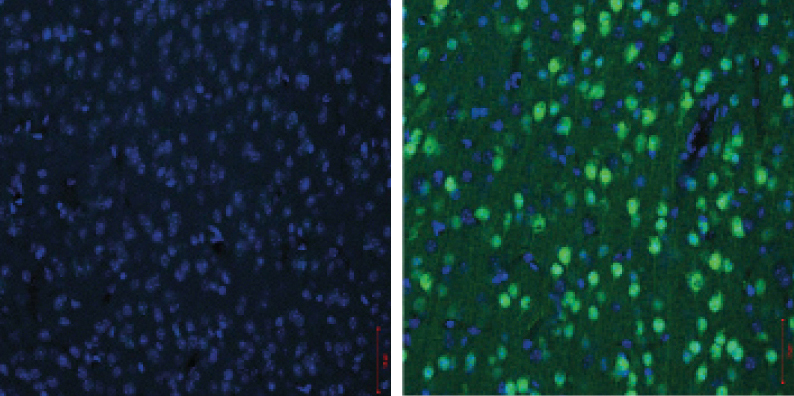

Philpot’s team first suggested topotecan as an Angelman treatment in 2011 but abandoned it in part because of its severe side effects, including diarrhea. They looked at 13 other topoisomerase inhibitors and found 4 that also unsilence paternal UBE3A in cultured mouse cells.

Of the four, a compound called indotecan is the most effective. Unlike topotecan, it may not be pumped out of the brain, so it would be effective even at a low dose. The findings were published in August in Molecular Autism.

In an early trial for cancer, indotecan appeared to be better tolerated than topotecan and does not cause severe diarrhea, says Mark Cushman, distinguished professor of medicinal chemistry at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

Like topotecan, indotecan may block the expression of other long segments, including long genes linked to autism, which could produce unpredictable side effects. But so far, it’s a promising candidate, says Ype Elgersma, professor of neuroscience at Erasmus University in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, who was not involved in this study.

“It really comes down to [whether you] could find a dose that UBE3A is still very sensitive to, because it’s a really abnormally long transcript, whereas the vast majority of your genes would have no problems marching on,” he says.

Brain benchmark:

Elgersma’s team showed in 2015 that unsilencing UBE3A in a mouse model of Angelman eases some of the syndrome’s hallmark behaviors — but is only effective until 6 weeks of age, the mouse equivalent of adolescence.

The mutant mice show more excitation than inhibition in their prefrontal cortex, Elgersma’s team found in the second new study. Restoring UBE3A expression resets the brain to the typical excitation-inhibition balance, even in adults, they found. The findings appeared 12 September in The Journal of Neuroscience.

“We were really surprised to see that if we took the adult mice and switched the gene back on, this rescued every single [brain] parameter that we had initially defined,” Elgersma says.

The findings suggest that treatment might help adults with Angelman in subtle ways, even if the improvement is not obvious in mouse behavior.

The results also suggest that researchers should carefully consider whether behavior or brain function is a better benchmark of an Angelman treatment’s success in mice, says Seth Margolis, associate professor of biological chemistry at Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore Maryland, who was not involved in either new study.

“We have to ask, ‘What is the most important or relevant aspect with the model system in thinking about ultimately treating the patient?’” Margolis says.

In the meantime, Philpot and Elgersma’s teams are trying other methods to activate paternal UBE3A and treat Angelman syndrome.

References:

Recommended reading

Documenting decades of autism prevalence; and more

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Perturb and record’ optogenetics probe aims precision spotlight at brain structures