Brains of people with autism show altered growth with age

Several brain regions in people with autism become enlarged earlier than usual during childhood and shrink too soon during adulthood, finds an eight-year imaging study.

Several brain regions in people with autism become enlarged earlier than usual during childhood and shrink too soon during adulthood, finds a study published 7 November in Autism Research1.

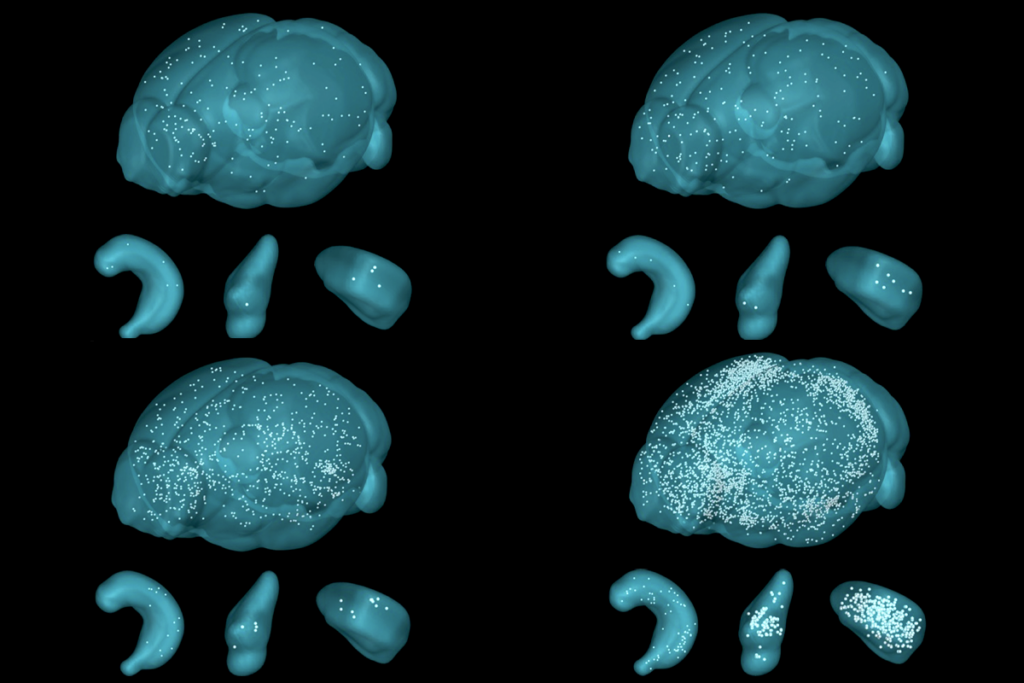

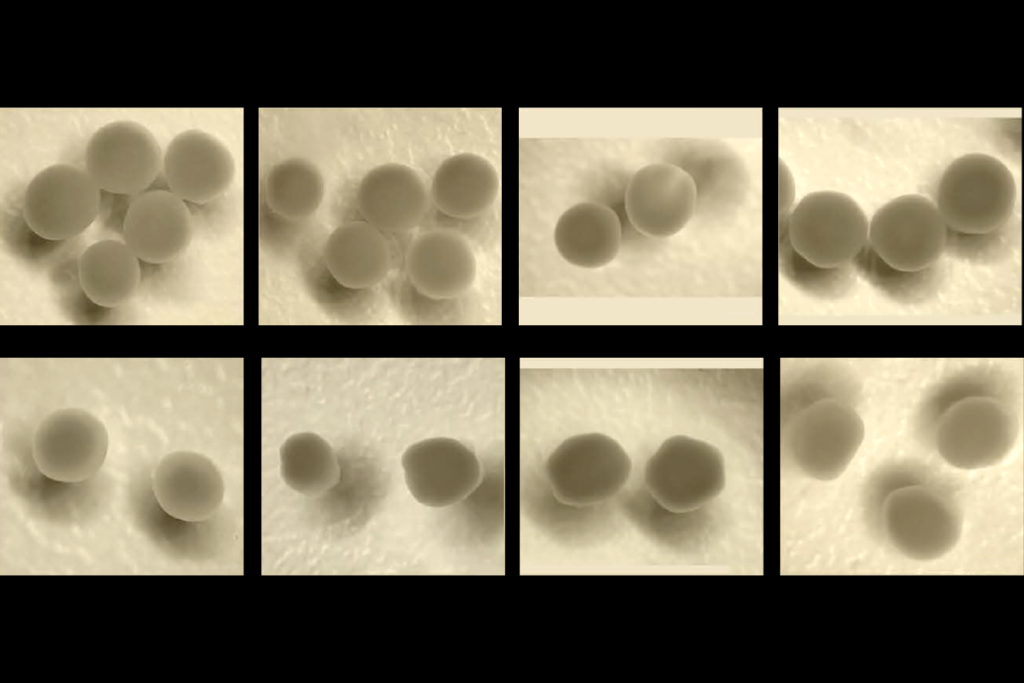

The study used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to track brain volume in 100 males with autism and 56 controls, all ranging in age from 3 to 35 years, over an eight-year span.

Total brain volume in boys with autism tends to be larger than that of controls before age 10. This difference fades between ages 10 and 15, as brain volume in controls increases. After this period, controls continue to show gains in brain volume until their mid-20s, whereas the brains of people with autism begin shrinking.

“People with autism miss the increase in brain volume in those younger years,” says lead investigator Nicholas Lange, associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard University’s McLean Hospital. That coincides with the transition into adulthood, which is particularly challenging for some people with the disorder. “They are faced with new demands, and they have less brain resources to deal with that,” Lange says.

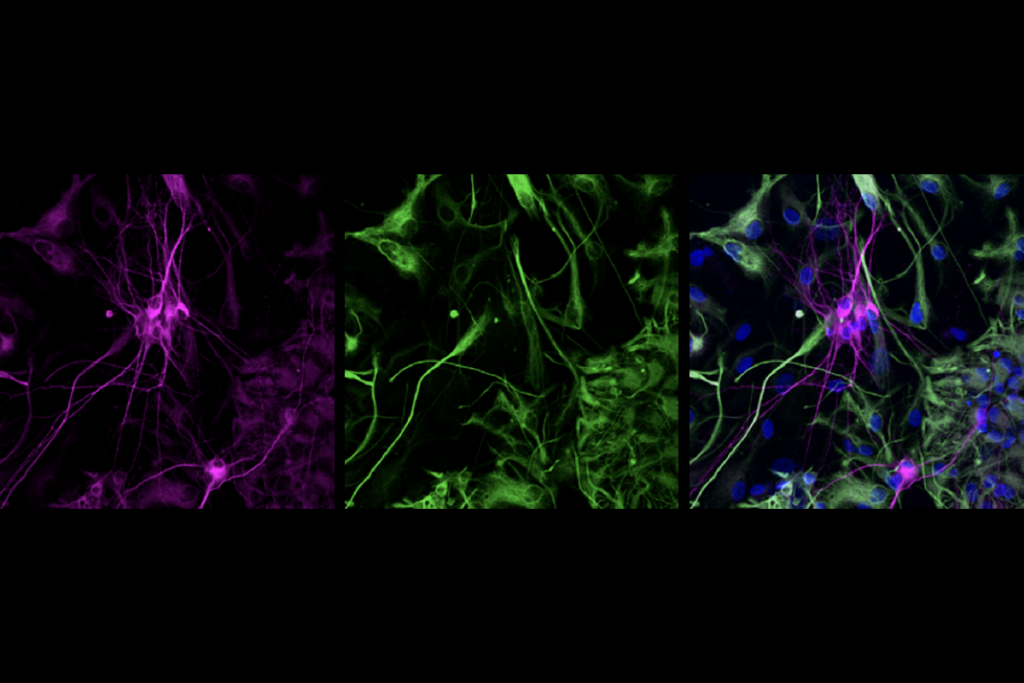

The researchers saw similar growth patterns when they focused on 11 brain regions and structures, including the corpus callosum, thalamus, cerebellum and several parts of the cortex, all of which have been implicated in autism. The changes occur both in the gray matter, which primarily consists of neurons’ cell bodies, and in the white matter tracts comprising the long, thin projections of neurons.

“We tend to think that [brain changes] are a pretty static event that happens in utero, or in the first few years, and they’re obviously not,” says Joseph Piven, professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the study.

Altered anatomy:

The study is not the first to look at age-related brain changes in people with autism. A 2011 analysis of brain imaging data from 259 people with autism and 327 controls also found that the brains of people with autism grow too quickly during childhood, and shrink too fast during adulthood2. But this study and others relied primarily on cross-sectional data, which means that most participants had a single brain scan at one point in time. The studies inferred age-related brain changes by comparing results in participants of different ages.

By contrast, the new study incorporates both cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Roughly half of the individuals with autism underwent three scans during the eight-year period, and more than 70 percent of the participants in both groups had at least two scans.

“That’s really excellent, because the more points you have, the more confident you can be in the trajectory that they’re plotting,” says Eric Courchesne, professor of neurosciences at the University of California in San Diego. Courchesne led the 2011 study but was not involved in the latest research. “This is one of the bigger longitudinal studies that have been done on brain volume changes in autism, and it is also one of the most comprehensive,” he says.

Still, the new study has relatively few controls at the extremes of the study’s age range. This limits the researchers’ ability to compare the youngest and oldest individuals in the two groups, says Armin Raznahan, a staff scientist at the Child Psychiatry Branch of the National Institute of Mental Health, who was not involved in the study.

The few studies that have tracked brain volume changes over time have focused on specific structures within a narrower age range. For example, a 2012 study of 23 boys with autism and 23 controls aged 7 to 16 years found a comparable rate of growth in the corpus callosum — the tract of nerve fibers that connects the brain hemispheres — over a two-year period3. A follow-up last year reported an accelerated rate of brainstem growth in the autism group over the same period.

The new study suggests that the volume of gray matter in several regions of the cortex across the parietal, occipital and frontal lobes declines earlier than usual during adolescence in the brains of people with autism than in controls. Adolescents with autism also show an abnormal delay in the increase of white matter volume in the cortex. “There are fewer neurons but also less connectivity in autism,” Lange says.

Lange and his team are working to tease apart the mechanisms underlying the brain changes in people with autism and whether these changes track with certain mutations or behaviors. At the time of each brain scan, the participants completed a series of standardized tests of social communication. The researchers are also sequencing DNA from each participant.

“Autism is a lifelong disorder, with behavioral and cognitive impairments that often increase with age,” Lange says. “I think these changes are very understudied in terms of the brain-behavior connection.”

References:

1. Lange N. et al. Autism Res. Epub ahead of print (2014) PubMed

2. Courchesne E. et al. Brain Res. 1380, 138-145 (2011) PubMed

3. Frazier T.W. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42, 2312-2322 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

Gene-activity map of developing brain reveals new clues about autism’s sex bias

Parsing phenotypes in people with shared autism-linked variants; and more

Boosting SCN2A expression reduces seizures in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Diving in with Nachum Ulanovsky