Brains of children with autism change as they grow up

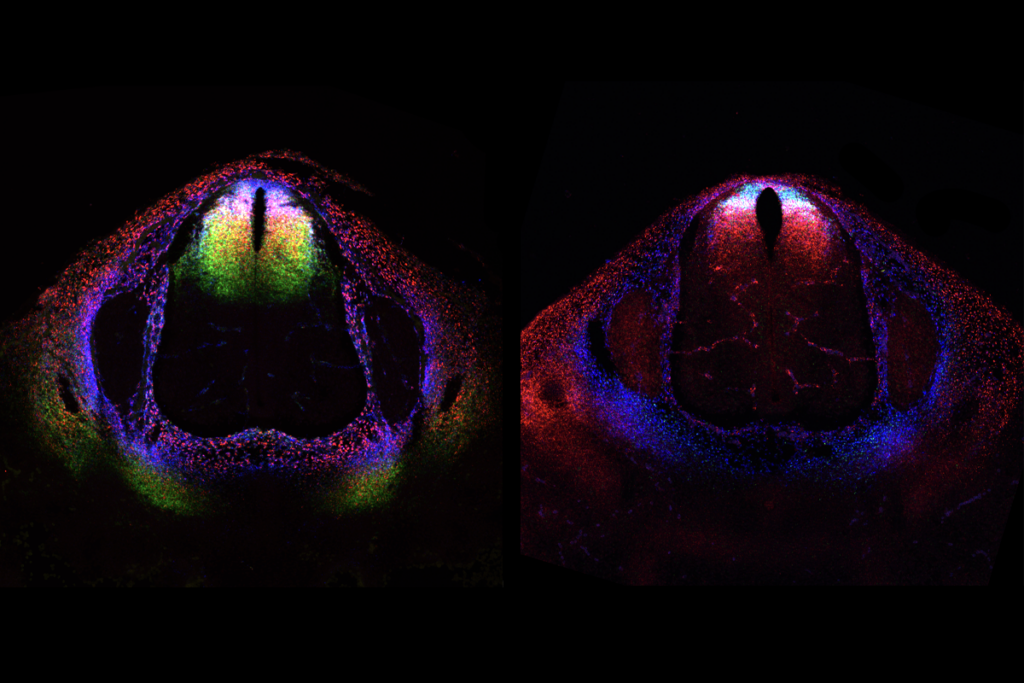

The brains of children with autism show differences in gene expression compared with those of healthy controls, especially in genes that control cell growth. Adults with autism also have aberrant gene expression, but in different pathways, researchers reported Sunday at the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

The brains of children with autism show differences in gene expression compared with those of healthy controls, especially in genes that control cell growth. Adults with autism also have aberrant gene expression, but in different pathways, researchers reported Sunday at the Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

Identifying which cellular processes go awry in the developing brain could help researchers understand why many children — but not adults — with autism have larger heads, says Maggie Chow, a graduate student in Eric Courchesne‘s laboratory at the University of California, San Diego.

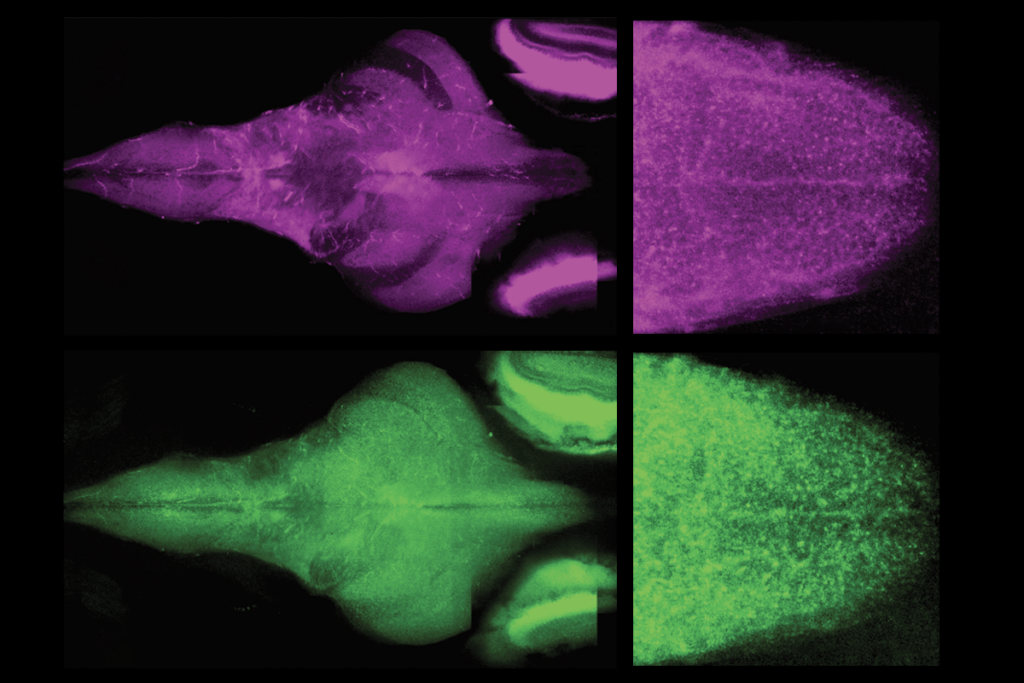

To address this question, researchers looked at changes in gene expression in two sets of postmortem brains: those from children between 2 and 14 years, and those from adults between 15 and 56 years. The researchers compared a total of 15 brains with those from 18 healthy controls.

Children’s brains had the most dysregulation in genes involved in the cell cycle — which prevents unchecked cell growth — and in apoptosis, which destroys unwanted or damaged cells. Dysfunction in both of these pathways could lead to many more cells in the brain.

The researchers also show that mutations in genes involved in the cell cycle are more likely in people with autism, suggesting that the defects in the cell cycle could be inherited.

By contrast, adults with autism have a completely different pattern of dysregulated genes, primarily involving signaling pathways, with only a few linked to the cell cycle or to apoptosis.

Some of the genes dysregulated in the young autism brains are involved in brain organization. This is exciting, Chow says, because the brains of people with autism show a gradient of abnormality from front to back, with the frontal regions being more enlarged.

The team is particularly interested in one gene, PCSK6, which contributes to left- or right-handedness. A study published in November links PCSK6 to reading and language delay in children with dyslexia. A defect in language is one of the core deficits in autism.

For more reports from the 2010 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

Largest leucovorin-autism trial retracted

Pangenomic approaches to the genetics of autism, and more

Latest iteration of U.S. federal autism committee comes under fire

Explore more from The Transmitter

Neuro’s ark: Understanding fast foraging with star-nosed moles

NIH scraps policy that classified basic research in people as clinical trials