Brain signature characterizes boys with autism

Activity in the social brain circuit can distinguish a boy who has autism from a typically developing boy with 76 percent accuracy.

Activity in the social brain circuit can distinguish a boy with autism from a typically developing boy with 76 percent accuracy, according to a new study1. This brain signature may also offer a way to track boys’ progress with behavioral treatments.

The study extends a 2010 report by the same team, which showed the social brain circuit is less active in a group of boys with autism than it is in controls2. But those findings were averaged across the entire group, and so are not clinically useful.

The new work carries the findings to the level of individuals. It also pinpoints a pattern that may, at a group level, track with the severity of social problems, says lead researcher Kevin Pelphrey, director of the Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Institute at George Washington University in Washington, D.C.

“Before, we could only say something about the group in general. Now we can really get closer to what we ultimately want to do — which is talk about an individual,” he says. The results were published in April in JAMA Psychiatry.

Pelphrey’s team validated the 2010 results in an entirely new set of boys — the kind of validation that is rarely done, says Shafali Jeste, assistant professor of psychiatry and neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the work.

“I think it’s a huge strength of the paper,” she says. “Very often, papers are published that are really interesting and possibly meaningful, and they’ve never been replicated.”

The work also comes with important caveats: The researchers didn’t test the signature in boys with other neurodevelopmental disorders, which would be needed before it could be used to diagnose autism. And the findings do not extend to girls with autism.

Biological motion:

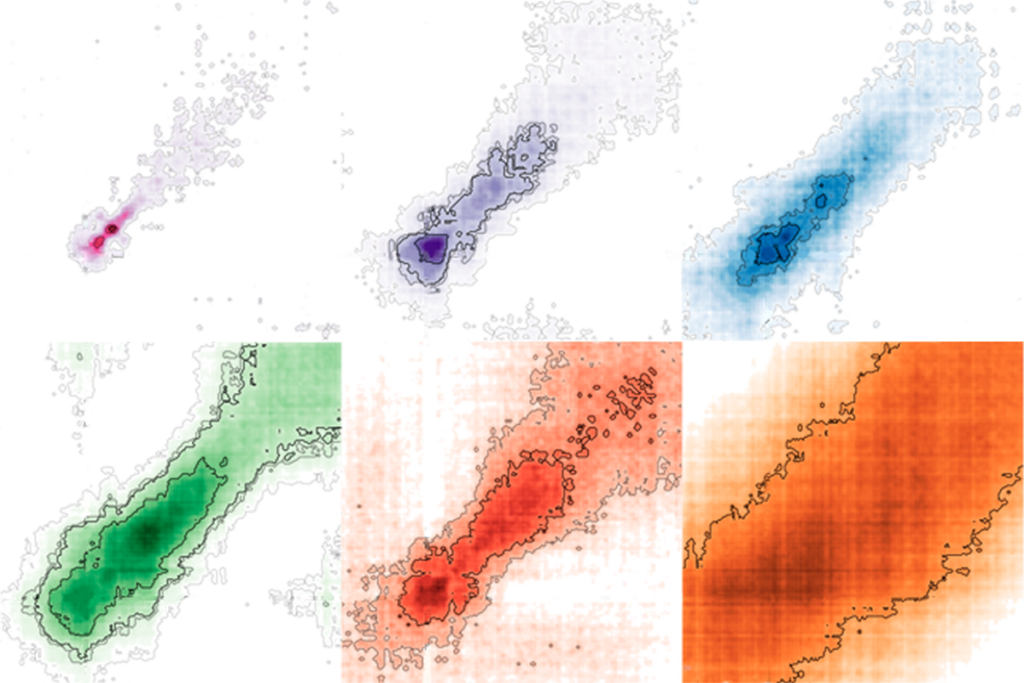

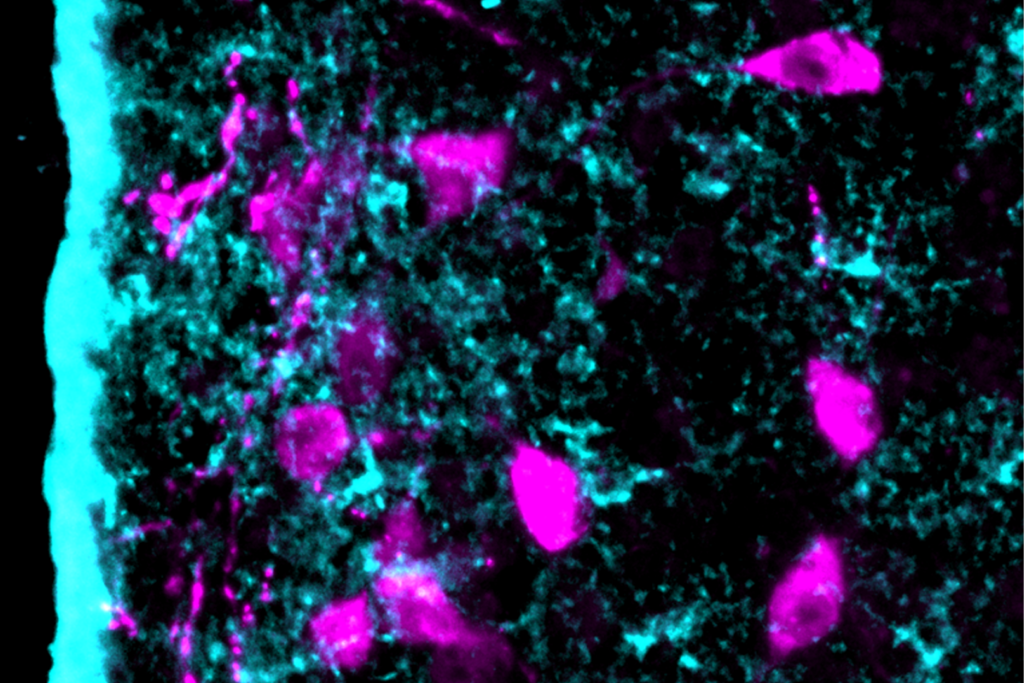

In their initial work, Pelphrey and his team showed 18 boys with autism and 12 typically developing boys videos of moving dots while scanning the children’s brains using functional magnetic resonance imaging. Half of the time, these dots took the shape of a person doing familiar tasks, such as walking or playing pat-a-cake. The rest of the time, the dots appeared to move at random.

When typical boys watched the videos of dots that looked like people, their brains responded with a boost in activity in a network of brain regions implicated in social perception: the superior temporal sulcus, fusiform face area and occipital gyrus. The brains of boys with autism, however, did not respond to the apparent ‘biological motion’ with an increase in activity in these regions.

In the new study, the researchers ran the same experiment in another 27 boys with autism and 25 typical boys. Instead of searching for differences between the groups, Pelphrey’s team looked to see whether their prior finding held up in individuals in the new group. It did.

The researchers also looked for responses to biological motion in these same brain regions in 14 girls with autism and 18 typical girls, and did not find any significant differences between the groups. “The really surprising thing that blew us away is how badly this measure worked for girls,” Pelphrey says. This result bolsters the theory that the brains of girls with autism function differently than those of boys, although why this is so is unclear.

Girl talk:

The discrepancy underscores the importance of analyzing girls with autism separately from boys. Most studies don’t enroll enough girls with autism to be able to run those analyses, however.

Preliminary data from Pelphrey’s lab suggest that other patterns of social brain activity might distinguish girls with autism. To find these patterns, researchers would need to look for differences in the brain’s response to biological motion between girls with autism and typical girls.

There is accumulating evidence that the brains of girls with autism are distinct from those of boys with the condition, says Christine Wu Nordahl, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis. Nordahl was not involved in the new study but has unpublished evidence of structural differences in the brains of girls versus boys with autism. Still, the low numbers of girls in her own and other autism studies make it difficult to tell whether these differences are real, she says.

Bucking this trend, Pelphrey and his team have joined forces with researchers across the country. They have scanned the brains of 76 girls with autism so far, along with an equivalent number of controls, and are beginning to analyze the data. They aim to follow these girls through adolescence and adulthood to see how their brains change over time.

Among the questions Pelphrey and his colleagues plan to address is whether sex differences in autism are innate or a consequence of different life experiences. They also want to see whether gender-specific differences in brain activity predict outcomes in areas such as employment and independence, Pelphrey says.

References:

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers

Two neurobiologists win 2026 Brain Prize for discovering mechanics of touch