Brain signals hint at speech delay in babies at high autism risk

Some infants who have an older sibling with autism show weak brain signals at 3 months of age.

Some infants who have an older sibling with autism have weak brain signals as early as 3 months of age, according to a new study1. The weaker this brain activity, the worse a baby performs on a test of expressive language at age 1.

The findings point to a possible marker for language delay, a common feature of autism. Detecting language delay early could enable doctors to treat infants when their brain is most flexible.

“Changes in the brain occur well before even the most skilled and attentive clinicians could ever pick up signs and symptoms [of language delay],” says lead investigator April Levin, instructor of neurology at Boston Children’s Hospital.

The differences in brain activity crop up in the ‘baby sibs’ — children who have an older sibling with autism — regardless of whether they have autism. (About 20 percent of baby sibs go on receive an autism diagnosis, compared with about 1 percent of the general population.)

The results add to mounting evidence that aspects of autism are present in the brain before they can be detected through a child’s behavior. About 20 percent of baby sibs who do not have autism have delayed language development.

“There are early changes in brain development that precede when the behavioral symptoms emerge,” says Geraldine Dawson, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, who was not involved in the study.

Weak waves:

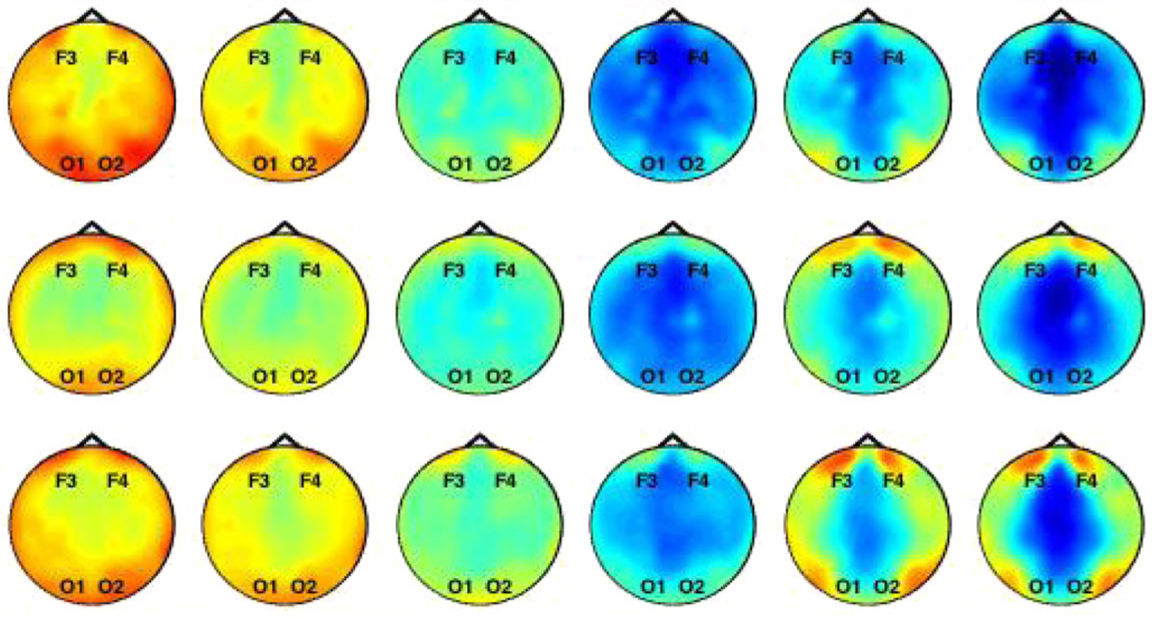

Levin and her colleagues used electroencephalography (EEG) to measure brain activity in 25 baby sibs and 14 control babies with no family history of autism. They also evaluated the children’s motor and language development at regular intervals between 6 and 36 months.

They diagnosed seven of the baby sibs with autism at 36 months of age. Eight of the controls did not meet the criteria for autism, but the study ran out of funding before the remaining six controls could be evaluated.

EEG uses electrodes placed on the scalp to detect activity of neurons firing in synchrony. Groups of neurons generate EEG signals of varying amplitude — or strength — and frequency.

The researchers compared the signal at each electrode with the average signal from all the other electrodes. They focused on the power of the signals, which reflects both the amplitude and synchrony of neuronal firing.

They found that baby sibs have weaker signals in the frontal region of the brain than controls do, regardless of whether they have autism. The weak signals occur in only two frequency bands, known as alpha and beta. Alpha waves are associated with speech processing, whereas beta waves tend to occur when a person engages in a task.

At 12 months of age, the baby sibs have poorer expressive language skills, on average, than controls do. Babies with the weakest signal in the alpha band score the lowest on a measure of expressive language skills at 12 months of age. This association disappears at older ages, however. The findings appeared 13 September in the Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders.

Because EEG is inexpensive and easy to use, clinicians could use it to predict which baby sibs will have language delay. “It’s exciting to me to see markers developed using EEG, because it’s such an implementable procedure,” says James McPartland, associate professor of child psychiatry and psychology at Yale University, who was not involved in the study.

Alternate method:

Levin and her colleagues also reanalyzed their data using another method: They compared the power of the signal at each electrode with that of its nearest 10 to 20 neighbors (instead of to the overall average). This approach did not reveal any differences between the groups in alpha or beta signals in the front of the brain.

This finding suggests that the weak signals detected in the original analysis occur across large swaths of the frontal cortex, a small part of which is involved in speech, Levin says.

The findings show that the way researchers analyze EEG data can have a dramatic effect on the results, says Shafali Jeste, associate professor of psychiatry and neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the study. “We have to be mindful of that when comparing studies.”

The strength of alpha and beta bands in baby sibs does not correlate with skills other than language at any of the ages tested. But a larger study might also show a connection between these brain waves and poor language at 2 and 3 years old, Levin says.

References:

- Levin A.R. et al. J. Neurodev. Disord. 9, 34 (2017) PubMed

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain