Autistic children as young as 2 years old show differences in brain network structure from their non-autistic peers, according to a new study. Those differences vary between autistic girls and boys, the study also shows.

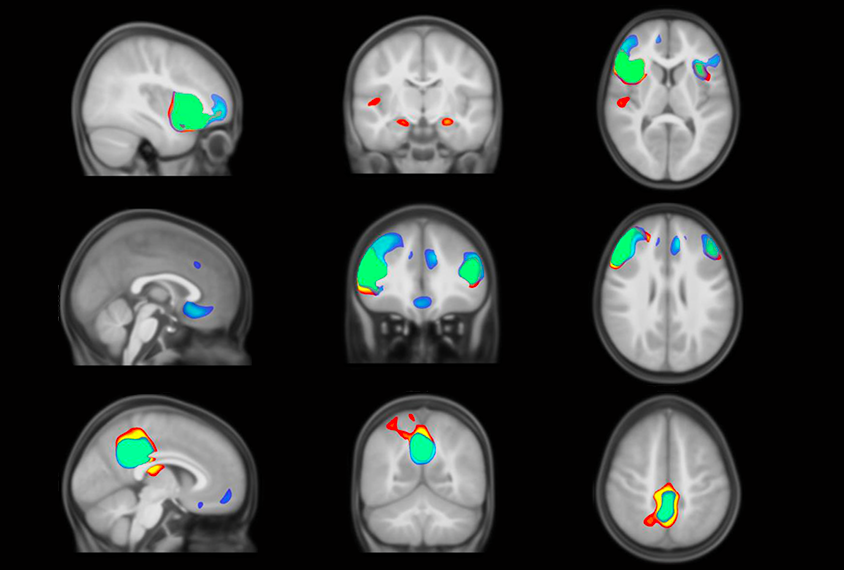

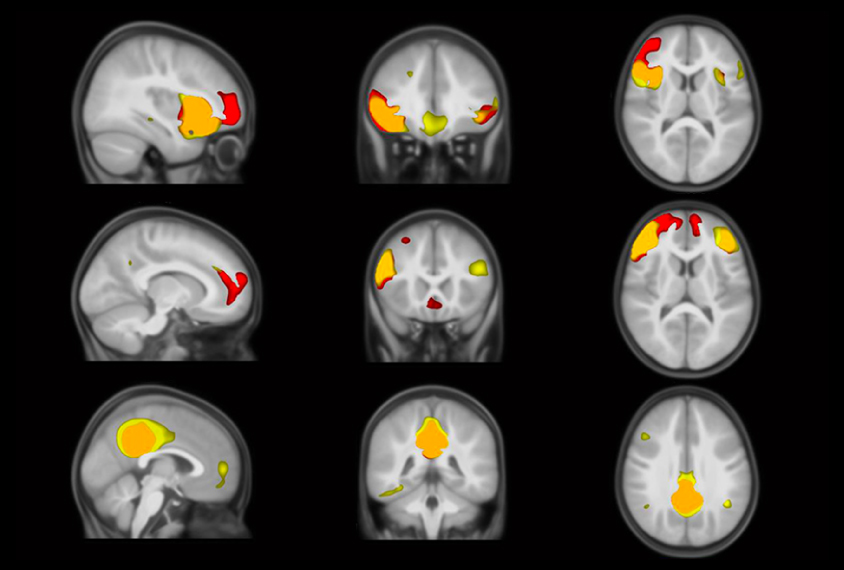

Functional brain-imaging data are difficult to collect in young children, especially in those with autism. Using ‘structural covariance magnetic resonance imaging’ to compare how gray matter density varies across brain regions within a network can serve as a proxy, says lead investigator Brandon Zielinski, associate professor of pediatrics and neurology at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

According to this measure, adolescents with autism have a smaller salience network, which is involved in directing attention to stimuli, and larger default mode network, which is active when a person’s attention is focused inward, than those without the condition, Zielinski found in 2012. The new results extend the findings to younger children.

Identifying such differences closer to the age at which autism is diagnosed may help elucidate the origins of the condition, says study investigator Christine Wu Nordahl, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis, MIND Institute.

“Whenever we see brain structure differences in older individuals, I will think, ‘Is this really part of the etiology of autism, or is it life happening to somebody with autism?’” Nordahl says. “So it’s helpful to look earlier on.”

T

he researchers analyzed brain images from 122 autistic and 122 non-autistic children aged 2 to 4 years old, split equally by sex. Many of the autistic children also have intellectual disability.As in the 2012 study, autistic preschoolers have a smaller salience network and larger default mode network than those without the condition, the team found. They also have a smaller executive control network, which governs cognitive functions needed for everyday tasks. In addition, the primary auditory cortex tends to connect with the salience network in autistic children only, though this finding was not statistically significant.

The differences “intuitively and theoretically map on to what we see clinically in the young people with autism,” such as difficulties with executive functioning and sensory processing, says Janet Lainhart, professor of psychiatry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was an investigator on the 2012 study but was not involved in the new work.

The networks studied were all more distributed across the brain in girls than in boys, regardless of diagnosis. More brain regions aligned with the three networks in autistic than non-autistic boys, whereas fewer brain regions aligned with the salience and executive networks in autistic girls than non-autistic girls. Girls with autism showed no differences from those without in the default mode network. The findings were published in NeuroImage in April.

The results underscore the need for more imaging studies in autistic girls, both Nordahl and Zielinski say. “The female story in autism has been under-told,” Zielinski says. “And this at least is an indication that there is a story there.”

T

he study is “impressive,” says Shulamite Green, assistant clinical professor of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the work. “It’s no small feat to get good MRI scans with almost 250 toddlers and preschoolers.”Some network variation may be missing because the team did not account for behavioral differences among the autistic children, she says. And it would be useful to compare the findings with resting-state functional MRI, a more commonly used method.

The findings show that interventions may need to happen early in life to have an effect, says Kaustubh Supekar, clinical associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford University in California, who was not involved in the work.

“The differences are pronounced,” he says. “That means we need to go earlier than 3 years to do something about it.”

The fact that the toddlers and the adolescents have a similar network structure, however, doesn’t necessarily mean the networks are “hardwired” at a young age, both Zielinski and Nordahl say. Rather, they likely vacillate over time.

Investigating whether network-level discrepancies actually lead to changes in behavior will be important, Supekar says. The salience network, for example, doesn’t correlate with autism behaviors in sex-specific ways, Supekar reported in February.

That question is among the researchers’ next steps, Nordahl says. They also hope to examine structural covariance in scans of the children at different ages, she says — many have now reached adolescence.