Brain imaging reveals brain stem alterations in children with autism

Children with autism show different patterns of connectivity than controls do in the brain stem regions associated with balance.

Children with autism show different patterns of connectivity than controls do in brain stem regions associated with balance. Researchers presented the unpublished findings yesterday at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

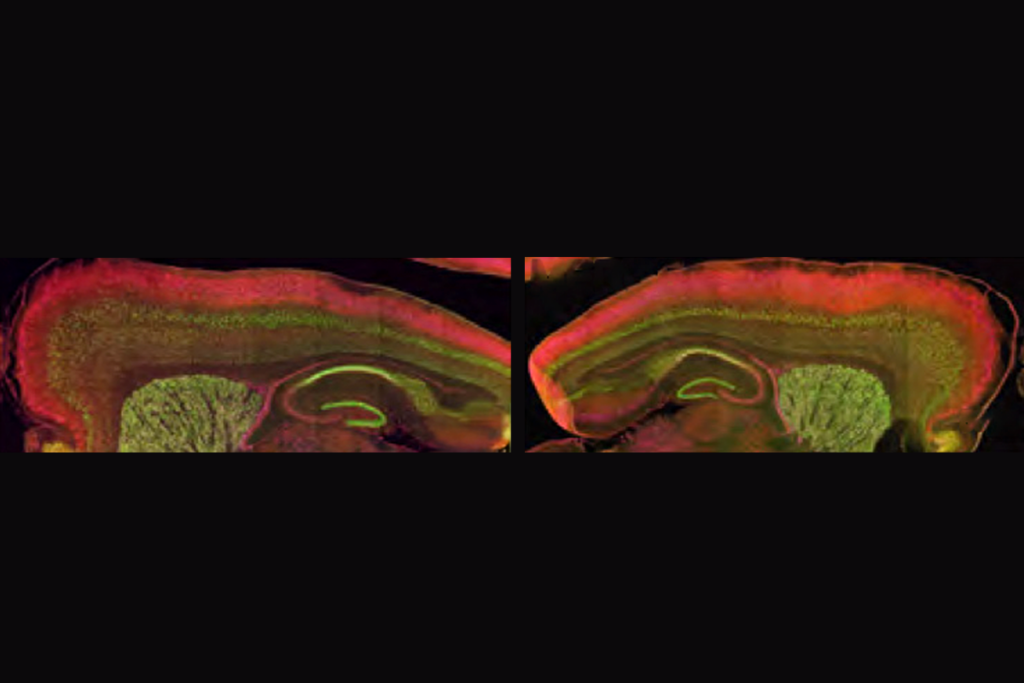

The connections in the brain stem are associated with balance and motor skills, both of which are known to be frequently affected in autism.

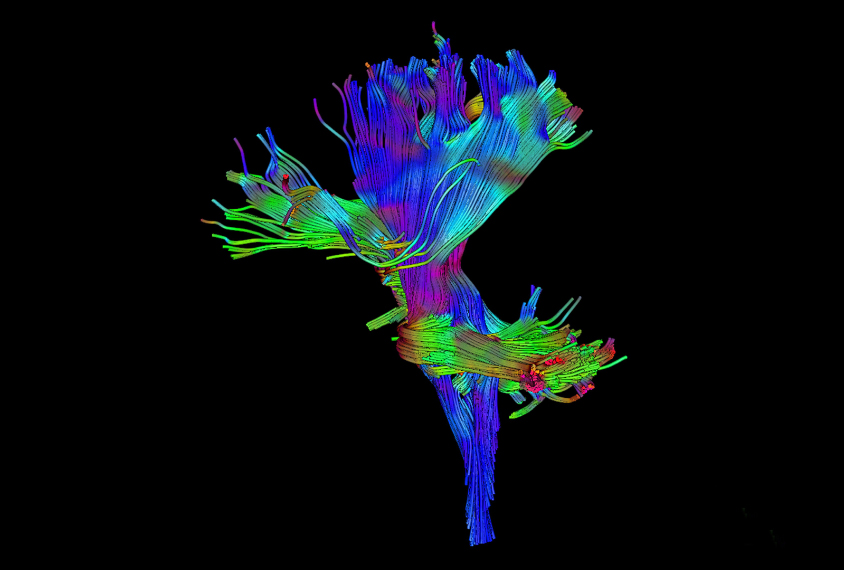

Few imaging studies in autism focus on the brain stem because it is structurally complex. It is the way station between the brain and the spinal cord, and is also near blood vessels and cerebrospinal fluid. Both substances can interfere with imaging techniques that measure water flow across the tracts of nerve fibers.

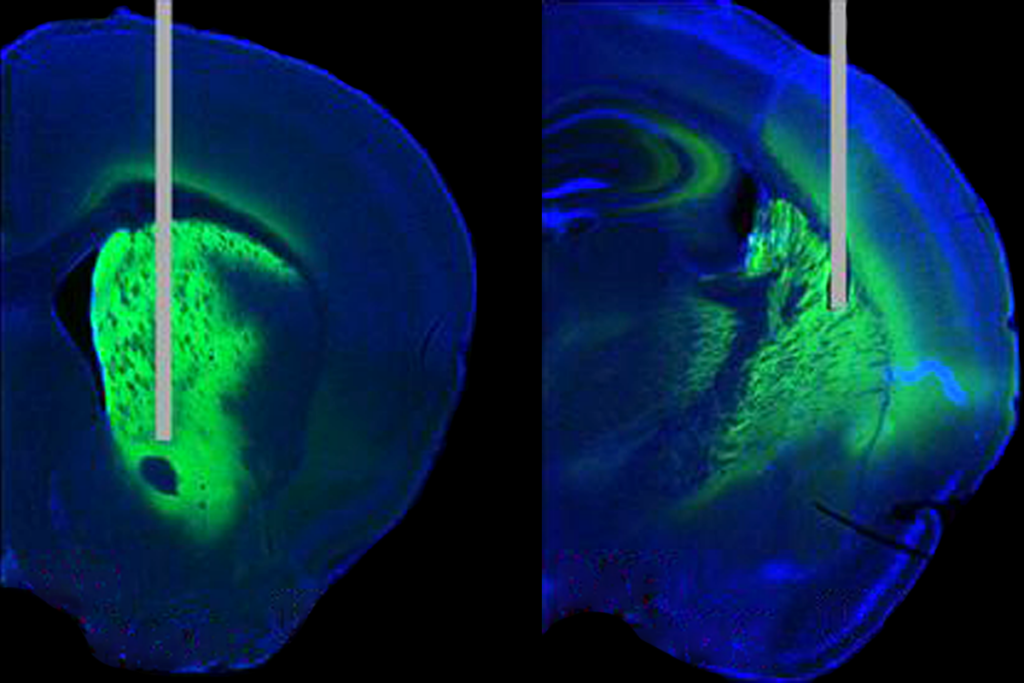

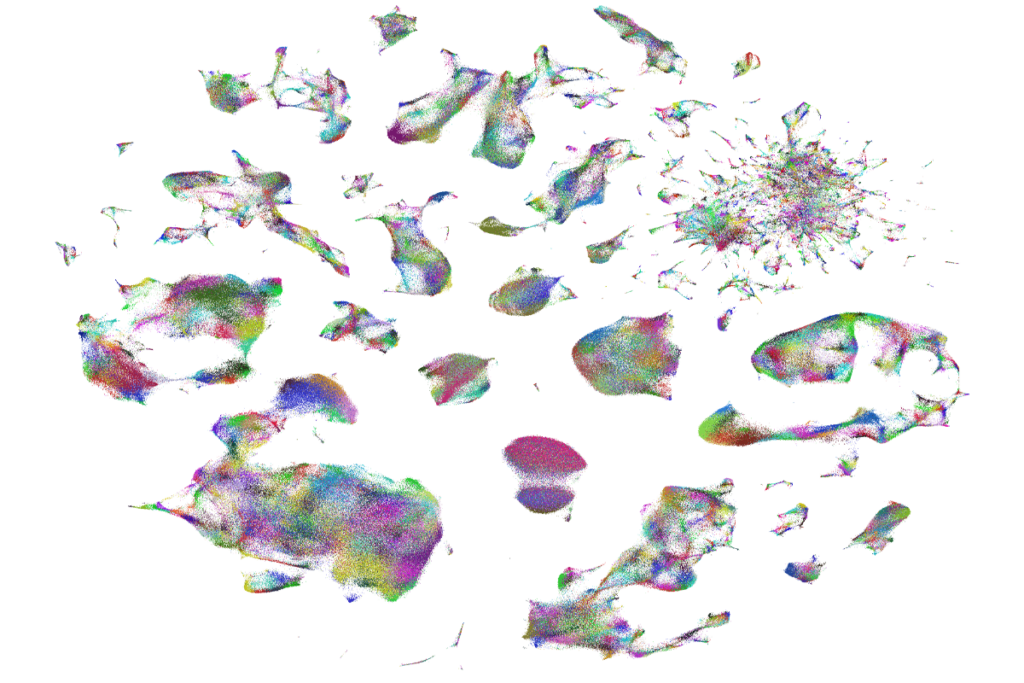

In the new work, the researchers used a technique called diffusion weighted imaging (DWI). This technique detects the motion of water molecules that diffuse through the brain, allowing researchers to visualize the brain’s structural connections.

The researchers looked at connections within the brain stem in 17 children with autism and 26 controls aged 6 to 10 years. They homed in on two nerve fiber tracts that run through the brain stem: the corticospinal tract, which relays motor information from the brain to the body; and the medial lemniscus, which receives sensory information from the body and delivers it to the brain.

The children also performed a range of motor and balancing tasks, such as standing on one foot and bouncing a ball.

Balance beams:

Among the typical children, balance seems to improve with age, because the older children performed better than the younger ones. But the children with autism all have about the same ability to balance.

The children with autism also have unusual connectivity patterns as measured by DWI.

Among controls, the researchers found that the lower the diffusivity of water across the medial lemniscus, the better the child’s balance. In the autism group, by contrast, better balance is associated with high rates of diffusion.

Low diffusivity can indicate that white matter is maturing. So the findings suggest that white matter in the children with autism has less structural integrity than the white matter in controls. As a result, children with autism may have to work harder to balance, engaging more brain resources to do so, says Olga Dadalko, a postdoctoral fellow in Brittany Travers’ lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who presented the work. The researchers found the same correlations for other motor tests.

But it’s still unclear why children with autism would have high diffusion rates. “The in vivo studies cannot tell you the precise mechanism,” Dadalko says.

The researchers also measured the children’s grip strength using a handheld device called a dynamometer. Previous studies have shown that children with autism have a weaker grip than typical children do.

In the new work, researchers found the children with autism are just as strong as controls. (It’s unclear why the two studies have contradictory findings, Dadalko says.) The children’s strength and motor skills improve with age, as they do in controls. There is no significant difference between the groups in the DWI measures associated with grip strength.

The researchers plan to exclude children in the control group who have conditions similar to autism. The control group in this study included children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, for example.

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Corrections

A previous version of this article misattributed to Olga Dadalko the idea that children with autism have less structural integrity in white matter integrity than controls do.

Recommended reading

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Restoring excitation-inhibition balance in a mouse model of autism; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter