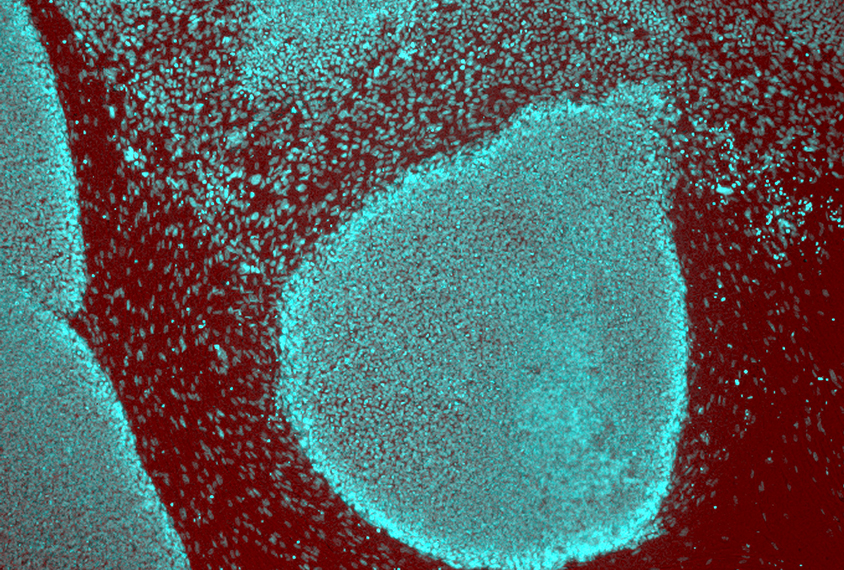

Silvia Riccardi / Science Source

Brain cells spun from skin point to subtypes of autism

Neurons derived from people with a syndromic form of autism look and behave differently than do those from people with classic autism.

Neurons derived from people with a genetic form of autism look and behave differently than those from people with autism of an unknown cause. The cells also show distinct gene expression signatures that mirror some of these differences.

Researchers presented the unpublished findings today at the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in Washington, D.C.

Several research teams are using so-called induced pluripotent stem cells to study autism. These cells are derived from skin cells and have the same genetic makeup as the donor. A cocktail of chemicals and growth factors transforms the cells into immature brain cells called neural progenitor cells, and eventually into neurons.

In the new work, researchers generated neural progenitor cells from two people with deletions of 16p11.2, a chromosomal region tied to autism, and two people with ‘idiopathic’ autism, meaning the condition’s cause is unknown.

“We compared the cells to see if there are any similarities or differences,” says Monal Mehta, a graduate student in Jim Millonig’s lab at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Brunswick, New Jersey. Millonig co-led the work with his Rutgers colleague Emanuel DiCicco-Bloom.

Neural progenitor cells from people with a 16p11.2 deletion divide more frequently than do those from controls, the researchers found. An analysis of gene expression revealed 11 genes within the deletion that are expressed in the cells. (The cells lack only one copy of this chromosomal region.) “Some of these 11 genes must be directly contributing to the [proliferation],” Mehta says.

Head start:

The findings could help to explain why some individuals with 16p11.2 deletions have enlarged heads.

Research from Paola Arlotta’s lab at Harvard University, also presented today, revealed a similar association between cell proliferation and head size in autism: Neural progenitor cells derived from people with idiopathic autism and enlarged heads divide more than do those derived from controls; the degree of proliferation tracks with head size, the team reported.

Previous studies have shown that people with autism have too few or abnormally shaped dendrites, the signal-receiving branches of neurons. DiCicco’s team reported today that neural progenitor cells derived from people with either a 16p11.2 deletion or idiopathic autism have too few branches.

Treating the cells with growth factors or the chemical messenger serotonin normalizes the number of branches in the 16p11.2 deletion neural progenitors but not in idiopathic autism progenitors, the researchers found.

“This may be relevant for what kind of therapeutics you give a person,” says Smrithi Prem, a graduate student in DiCicco-Bloom’s lab who presented the work. “If their cells respond [to the drug], it’s more likely the drug will work for them.”

Although the technique of generating neurons from skin cells is not new, researchers are developing innovative ways to analyze the cells.

“Now we have all this ‘-omic’ technology,” says Millonig, referring to tools that reveal a wide range molecular changes in the cells. “We hope to use these advances to identify subtypes of autism and possibly treatments.”

For more reports from the 2017 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Explore more from The Transmitter

Snoozing dragons stir up ancient evidence of sleep’s dual nature

The Transmitter’s most-read neuroscience book excerpts of 2025