Before sitting down to write his new book, released today, Cambridge University psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen joked with his editor that it could be the shortest book in the world — just three words long. Those words? If, and, then. “Sensibly,” he writes, “she asked me to elaborate on them.”

And that is exactly what the prolific and provocative autism researcher does in “The Pattern Seekers: How Autism Drives Human Invention.” The book is essentially a 272-page argument for Baron-Cohen’s hypothesis that all human innovation stems from what he terms the ‘systemizing mechanism’ — the ability to discern and manipulate causal patterns.

This cognitive mechanism, Baron-Cohen says, is particularly strong in innovators in all fields — the arts as well as the sciences — and also in people with autism, two groups that he believes have overlapped throughout history.

It is a bold argument, which he supports with a fair degree of conjecture and evidence marshalled from a range of fields, including archaeology, animal behavior and neuroscience. He concludes with an impassioned call to action for modern society to do a better job of tapping the inventive power of people with autism.

‘The Pattern Seekers’ spans the full sweep of human history. Somewhere between 70,000 and 100,000 years ago, the author argues, hominids evolved the brain power to think systematically using ‘if-and-then’ logic, and the result was the flowering of human invention.

Agriculture took root, he suggests, when a systemizing mind noticed that if a seed falls in moist soil, and the sun shines on it, then the seed will sprout. Through relentlessly focused repetition and experimentation in which a single variable is modified, each newfound pattern could be further tested, refined and exploited. Baron-Cohen describes this as adding more ‘ands’ to the if-and-then logic: If a seed falls in moist soil, and the sun shines on it, and I water it when there’s no rain, and I remove weeds, and I add dung to the soil, then the sprouts will flourish and I’ll have a crop.

Medicine, he supposes, began in a similar fashion: If I have a headache and I eat willow bark, then my headache goes away. Ditto with the invention of tools: If I sharpen a piece of flint and attach it to a long pole with some strong fiber, then I can use it to efficiently hunt prey from a safe distance.

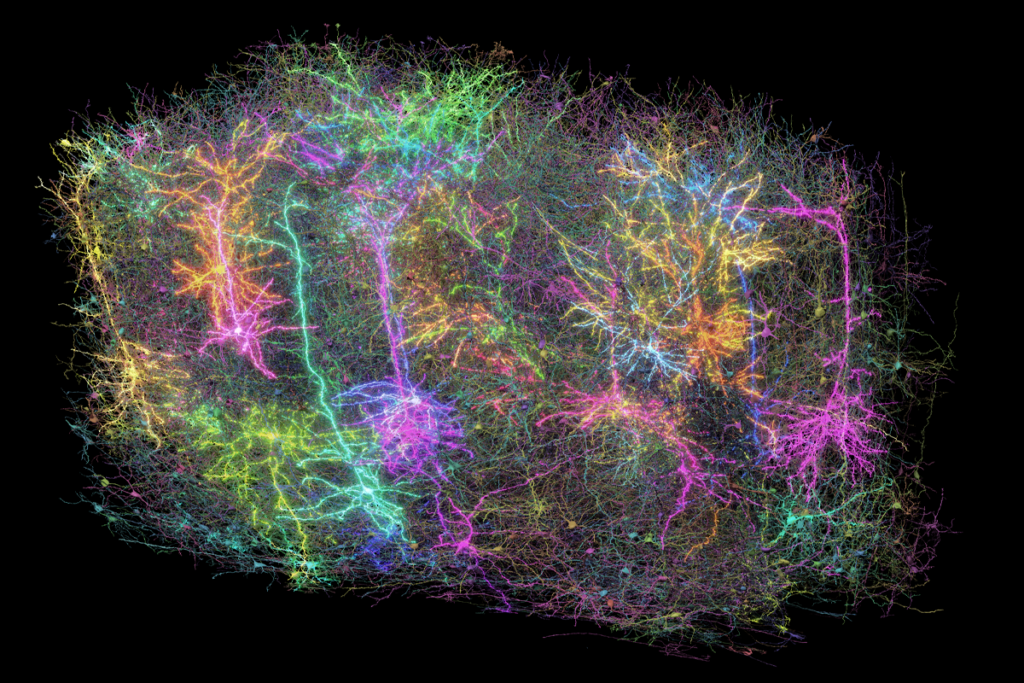

Baron-Cohen cites functional magnetic resonance imaging studies suggesting that this systemizing mechanism “depends strongly” on lateral frontoparietal connections in the brain and a region called the intraparietal sulcus.

He insists that the systemizing mechanism is unique to Homo sapiens and devotes an entire chapter to knocking down any suggestion that earlier hominids, including Neanderthals, possessed this capacity, despite their use of simple tools and fire.

In one of the book’s more entertaining chapters, Baron-Cohen reviews an array of clever animal behaviors that appear to reflect causal thinking: octopuses that use coconut shells as armor, dolphins that use sea sponges and conch shells as scavenging tools, and Australian raptors that set fires by dropping hot embers onto a dry field, forcing tasty field mice to scurry into view. But as he did with human progenitors, Baron-Cohen dismisses these as examples of ‘associative learning’ rather than systemized cognition.

Animal behaviorists and anthropologists may well take issue with Baron-Cohen’s audacious trespassing on their turf.

Readers who are familiar with Baron-Cohen’s theories and studies of autism will find many of his greatest hits in this latest volume. Among them is his notion that the brain in people with autism is essentially a hyper-masculinized brain, made so both by genetic variations and by prenatal exposure to high levels of androgens and estrogens in amniotic fluid. (His large studies with amniotic samples provide intriguing evidence for this idea1,2.)

An inveterate systemizer himself, Baron-Cohen has argued for more than a decade that people can be classified based on their scores along two dimensions: empathizing and systemizing, as measured with assessments of his own design. According to his own studies, about one-third of all people and 40 percent of women are Type E — strong on empathy and somewhat weaker on systemizing, another third of all people and about 40 percent of men are Type S — strong on systemizing and weaker on empathy, and a final third are Type B — with balanced abilities3.

But Baron-Cohen is particularly interested in the small subset of people — about 3 percent of men and 1 percent of women, according to his research — who are extreme systemizers: powerful, almost obsessive if-and-then thinkers who tend to be weak in empathy, particularly in their ability to understand another person’s mental state, an ability known as ‘theory of mind.’

Among these ‘hyper-systemizers’ he places historical figures such as Swedish botanist Carl Linneas, inventors Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, and modern innovators such as Microsoft founder Bill Gates and pianist Glenn Gould. Also in this category are people with autism, he says.

Although Baron-Cohen does not explicitly label any historic innovators as autistic, he does tell tales about the eccentric social behavior and restricted interests of several of them, particularly Edison, who was so enamored with Morse code that he nicknamed his first two children Dot and Dash.

Baron-Cohen clearly believes that among the many autistic people on the planet today are systemic thinkers with untapped powers to invent and create. The most moving and also pragmatic part of ‘The Pattern Seekers’ concerns this profound waste of potential.

Throughout the book, Baron-Cohen returns to the story of an autistic man he has worked with who, though baffled by ordinary conversation, has built up an encyclopedic knowledge of plants and an ability to precisely diagnose car trouble just from the sounds of an engine. And yet, despite applying for hundreds of jobs, this man, now in his 40s, remains unemployed. A job, he tells Baron-Cohen, would lift the depression and suicidal thoughts that beset him: “Why won’t anyone give me the chance to prove I can contribute, to make me feel included in society?”

Baron-Cohen points to several efforts to foster employment and productivity among autistic adults, including a special unit in the Israeli army. He calls for a pathway in schools that would allow autistic children to pursue their own narrow interests rather than flounder in a broad but shallow curriculum.

He acknowledges that many people with autism struggle with conditions and disabilities that limit their ability to contribute, but who could argue with his view that far too much talent is going to waste?

“When the hyper-systemizing qualities of autism are supported and nurtured,” he writes, “the unique skills and talents of autistic individuals can shine — to their benefit and to the benefit of society.”

Claudia Wallis is a health columnist and contributing editor for Scientific American. She is a former science editor for Time Magazine, and her work has also appeared in The New York Times, Fortune and The New Republic.