Blind dates for zebrafish reveal ‘social’ cells in brain

A new behavioral test in zebrafish may help researchers zero in on the biology of social interactions.

A new behavioral test in zebrafish may help scientists zero in on the biology of social interactions1.

Using their test, a team of researchers was able to home in on a neuron type and brain region that drive the zebrafishes’ interactions. Analogous cells and regions exist in people, so the test may help scientists trace social brain circuits altered in autism.

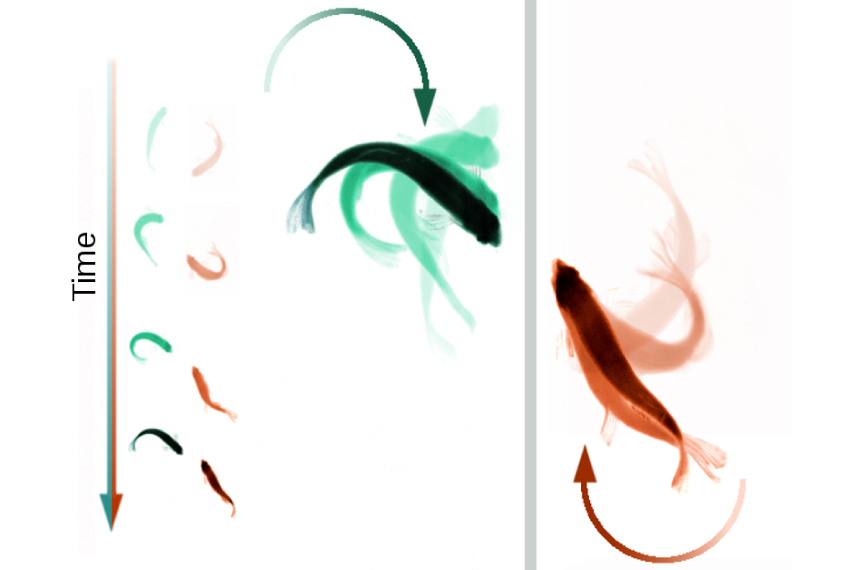

Wild zebrafish shoal (stay together) and school (swim in the same direction). When two zebrafish see each other, they turn toward each other or swim in parallel, depending on a variety of cues. These social behaviors can help the fish find a mate or food, and stay safe from predators.

In the test, the researchers place two adult fish into neighboring tanks divided by a wall. The wall is opaque but is designed to become transparent when an electric current runs through it. Once the fish see each other, researchers look for a change in swimming behavior.

An ordinary, solitary zebrafish swims in a random pattern in its tank. But upon seeing its neighbor, the fish orients its body so it makes a 45- to 90-degree angle with the divider, the researchers found. As a result, the zebrafish face each other, as they do in the wild.

The fish do not turn to face a fish-sized object the researchers place in the neighboring tank, showing that they need to see a fish, not just any visual stimulus, to change their behavior.

Zebrafish treated with a chemical that impairs social interactions in mice do not turn to face each other when the wall becomes transparent. This result indicates that the orienting behavior is social in nature.

Social cells:

By tracking the time each fish spends oriented toward another fish, the researchers can measure increases or decreases in their social behavior.

The team injured two brain regions in zebrafish and examined the effect on behavior. In some fish, the researchers injured the underside of the telencephalon, a region analogous to human brain areas that regulate memory, emotion and social behavior.

The damaged fish spend less time orienting toward their neighbor, indicating that the region is key to social behavior. Fish that sustain damage to the upper portion of the telencephalon, however, turn toward their neighbor just as controls do. Researchers described the test in August in Current Biology.

To find the cells underlying the social behavior, the researchers genetically deactivated different types of neurons in the lower telencephalon. They found that social orienting is disrupted only when a type of neuron that releases the neurotransmitter acetylcholine is deactivated.

The finding suggests that these neurons are responsible for the social swimming, and dovetails with the idea that a lack of acetylcholine can drive autism-like behaviors in mice.

References:

- Stednitz S.J. et al. Curr. Biol. 28, 2445-2451(2018) PubMed

Recommended reading

New tool may help untangle downstream effects of autism-linked genes

NIH neurodevelopmental assessment system now available as iPad app

Molecular changes after MECP2 loss may drive Rett syndrome traits

Explore more from The Transmitter

Organoids and assembloids offer a new window into human brain

Who funds your basic neuroscience research? Help The Transmitter compile a list of funding sources