Beware the hype

If you believe the hype about oxytocin, it’s nothing short of a wonder drug: it can make you trust a stranger, enhance a mother’s bond with her child and, according to a study published earlier this year, improve social skills in individuals with autism. But look more closely, and there is ample cause for caution.

If you believe the hype about oxytocin, it’s nothing short of a wonder drug: it can make you trust a stranger, enhance a mother’s bond with her child and, according to a study published earlier this year, improve social skills in individuals with autism. But look more closely, and there is ample cause for caution.

An editorial published in the August issue of Nature Neuroscience calls for guidelines to regulate oxytocin’s off-label use, and for scientists to educate the public on the pros and cons of such treatments.

I couldn’t agree more. As we begin to unravel the inner workings of the brain, we are also likely to learn how to manipulate it, potentially altering our very identity. In the most extreme scenario, people could resort to a kind of plastic surgery to tailor their personalities into an optimal — and arbitrary — norm.

The simple solution to regulating oxytocin’s abuse would be to limit its off-label use, restricting it to those with a medical disorder. But identifying when a disorder warrants treatment would require defining a normal brain. I find this prospect to be both staggeringly complex, and somewhat frightening. Who decides what is normal?

Autism is an especially complicated case as it is by definition a spectrum of disorders, and some high-functioning individuals are not significantly different than the so-called healthy population. There is also some merit to the movement that views autism not as a disorder, but as a form of ‘neurodiversity’.

As the editorial says, scientists should adopt some of the responsibility for the unintended consequences of their research. This isn’t a new topic, and debates over the ethics of research are as old as the splitting of atoms. The real question is not whether we should, but how? In this case, I believe scientists will need to share the responsibility with ethicists to develop thoughtful, but strict, guidelines for the off-label use of oxytocin and related drugs.

Recommended reading

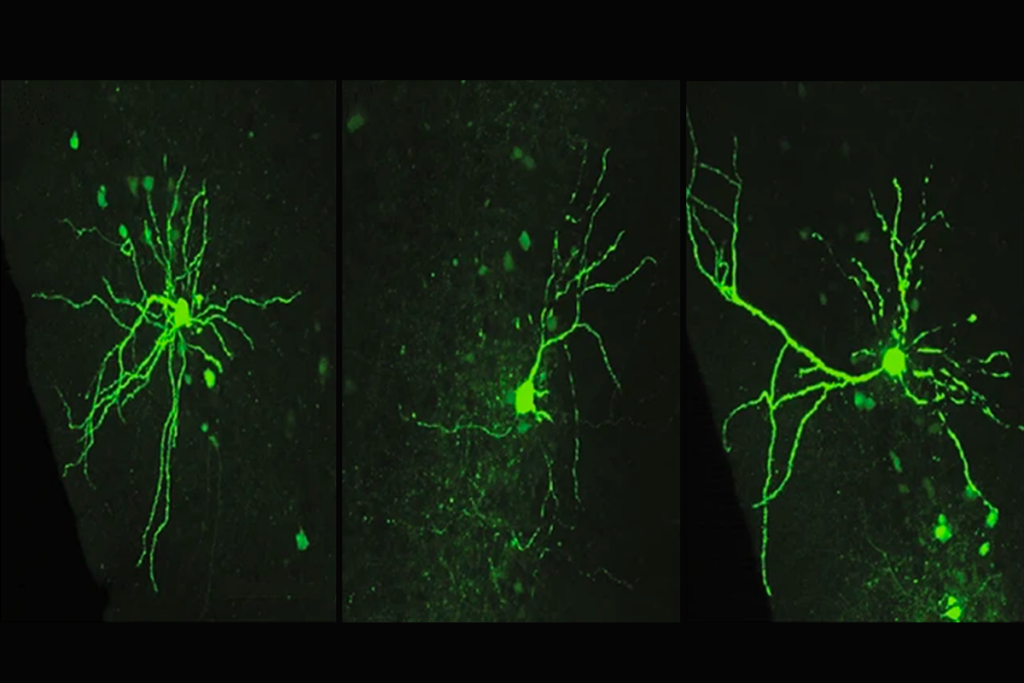

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

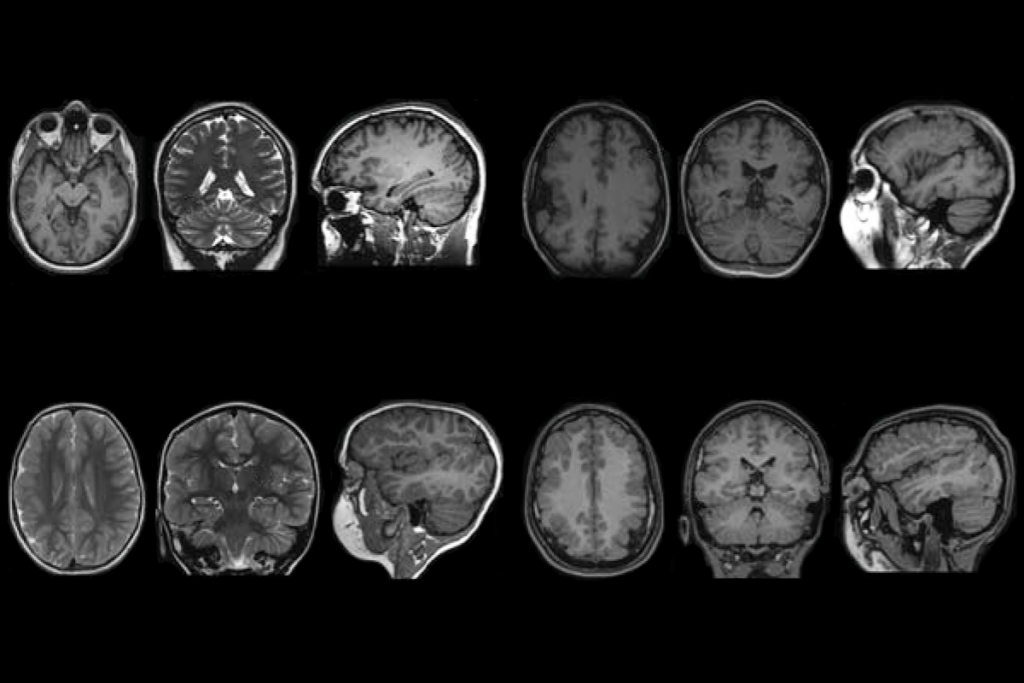

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence