Before talking about autism, listen to families

Scientists should phrase their findings to be sensitive to the dignity and needs of people with autism.

I take a deep breath before reading any article, popular or scientific, about autism. I steel myself because most of these stories paint people like my curly-haired, autistic teenage son as burdens to their families — as changelings or enigmas. I love my son Leo fiercely and consider him none of those things, so these stories hurt. My adult autistic friends are even more pained than I am by these puzzlingly negative portrayals.

Part of the problem is that in the mainstream media, researchers do not have much opportunity to directly describe their own research. Even when a journalist interviews a researcher, the core scientific message may get lost or misrepresented if the two parties do not accurately grasp each other’s goals.

Still, in many cases, autism researchers do have control over their message to the public.

Most have the best of intentions, but their goals don’t always translate into the types of benefits that autistic people and their families need most.

I’d like more researchers to take their influence on public perception seriously. So I have some advice for scientists about how to get the word out, whether they are reporting their findings in a journal or talking to the media. I’d also like to see them bring autistic people into the conversation early in the scientific process.

Words to the wise:

In writing for scientific journals, autism researchers can minimize negative connotation through word choice. Simply swapping ‘differences’ for ‘deficits,’ for instance, can skew perceptions of autistic traits and development more positively, and prompt readers to try to understand autistic people rather than to change them into non-autistic people.

Learning to recognize the features of autism instead of focusing on ‘deficits’ is crucial. No child deserves to be viewed as a collection of symptoms, yet that is the inevitable outcome of a deficit-based approach. ‘In need of repair’ was how autism experts initially conditioned me to view my son — an outlook I now regret. Leo is no less lovely for being immune to normalization.

Terms such as ‘high-’ or ‘low-functioning’ and ‘mental age’ may be convenient clinically, but they interfere with accurate perceptions of abilities and disabilities. To quote Laura Tisoncik in Autism Mind, “High-functioning means your deficits are ignored, and low-functioning means your assets are ignored.” I would prefer that scientists choose terms that focus on meeting the needs of autistic people instead, such as ‘low- and high-support,’ instead of those more judgmental words.

Blurring the lines:

For researchers speaking or writing about treatments in scientific venues, it is important to pinpoint the problem you are trying to solve. Do not say you are treating autism if your treatment applies to another condition that is merely related to autism. It’s true that autistic people have higher-than-average rates of epilepsy, gastrointestinal issues and anxiety, among other health issues, but those conditions are not intrinsic to autism. It’s not accurate to describe people whose epilepsy or anxiety, say, is under control as ‘less autistic’ when in fact their autism is unchanged. They are instead happier, healthier versions of their autistic selves.

Blurring the lines between autism and accompanying conditions also opens the door to peddlers of unhelpful or even dangerous ‘cures.’ The pseudoscience-based recovery industry preys on parents’ fears, reeling in families by targeting issues such as digestive problems and food allergies and asserting that treating those issues cures autism. In extreme cases, these misleading pitches can be fatal to autistic children.

Please avoid terms such as ‘recovery.’ Mounting evidence supports the idea that autism is prenatally wired. So unless there is some way to completely undo that key wiring, people labeled as ‘recovered’ most likely remain autistic but have simply developed skills for passing as non-autistic. Those who find eye contact uncomfortable may learn to look at the bridges of people’s noses instead of their eyes, as others rarely spot the difference. Autistic people may also rely on predetermined scripts for socializing, giving convincing but laborious impressions of spontaneous conversation. These masking tactics can not only be exhausting, but can result in losing one’s autism label and diagnosis-dependent accommodations. The combined result, as autism researcher Catherine Lord notes, can be a decline in mental, cognitive and physical health.

Instead of emphasizing recovery or cures, scientists should focus on accommodating the needs of autistic people and helping them learn new skills. That’s the kind of research that my son and our family need now.

Working together:

I’m grateful for recent investigations by scientists into sleep disturbances in autism and the under-diagnosis of girls, both of which are sorely needed. But we need more studies aimed at identifying and supporting autistic children of color and from different cultures. We also need to better understand why repetition-based approaches can derail autistic learning, and what that means for drill-based approaches such as applied behavioral analysis. We need systematic screenings for visual or auditory sensitivities that can impede classroom functioning. We also need a revolution in support strategies for autistic people with alternative communication needs.

I’d like to see more researchers consult and partner with autistic people to direct research according to the real-world needs of those who may benefit from it. Many autistic adults are raring to talk to researchers, not only because of their own interests, but also because they want to guide the conversation so that today’s children do not live through traumatizing attempts at normalization.

Guidance from autistic people about therapies is not hard to find, as they often opine publicly at conferences and in print. They may talk about the perils of normalization therapies, why food aversions need to be understood before they can be addressed, how their visual or auditory processing can change over time and why eye contact should not be a major focus, so to speak, of therapy. Researchers could transform the lives of many autistic people by exploring, verifying and spreading the word about these perspectives.

If more researchers keep autistic people and their families in mind as they describe and direct their studies, everyone involved would benefit. I look forward to the day I can approach the autism research literature with excitement instead of trepidation.

Shannon Des Roches Rosa is senior editor at Thinking Person’s Guide to Autism.

Recommended reading

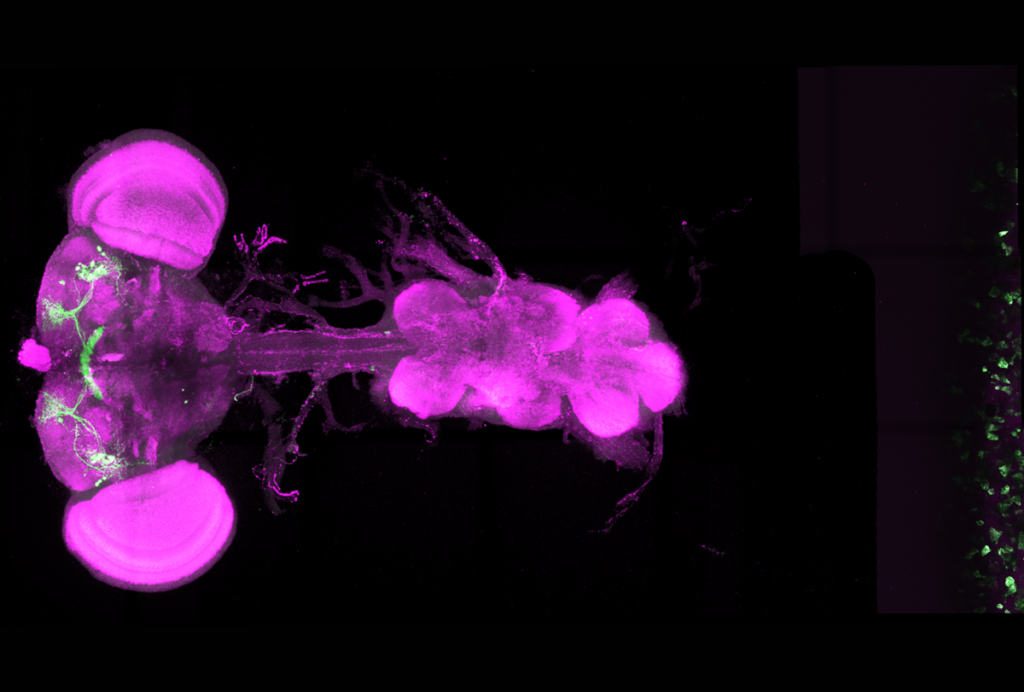

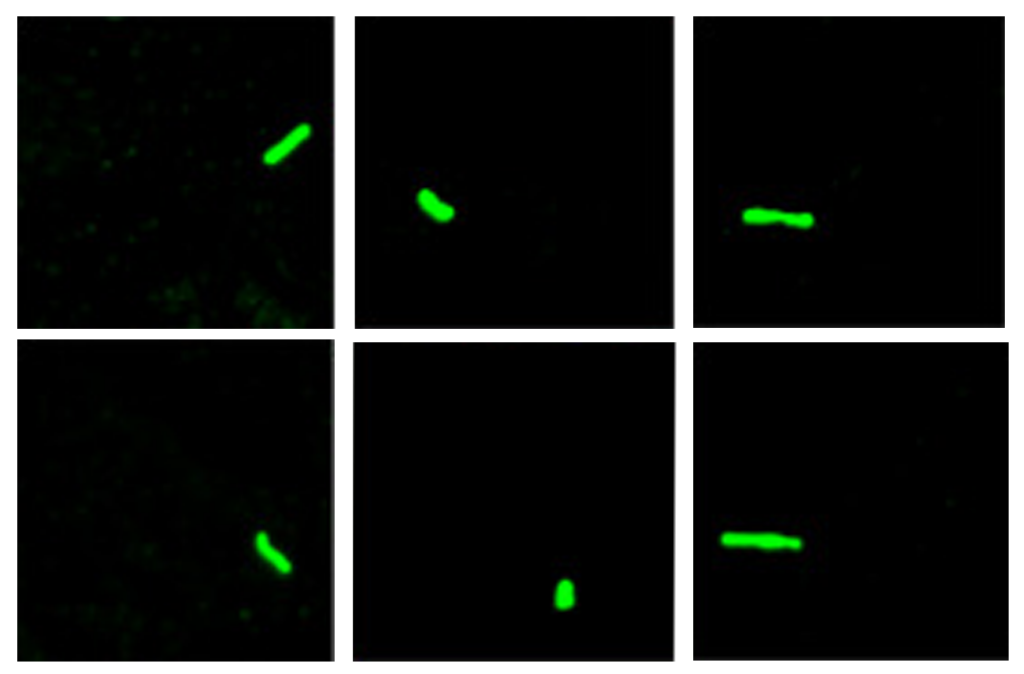

Sensory gatekeeper drives seizures, autism-like behaviors in mouse model

Protein interactions important to SYNGAP1-related conditions; and more

Autism-linked copy number variants always boost autism likelihood

Explore more from The Transmitter

Oxytocin shapes both mouse mom and pup behavior

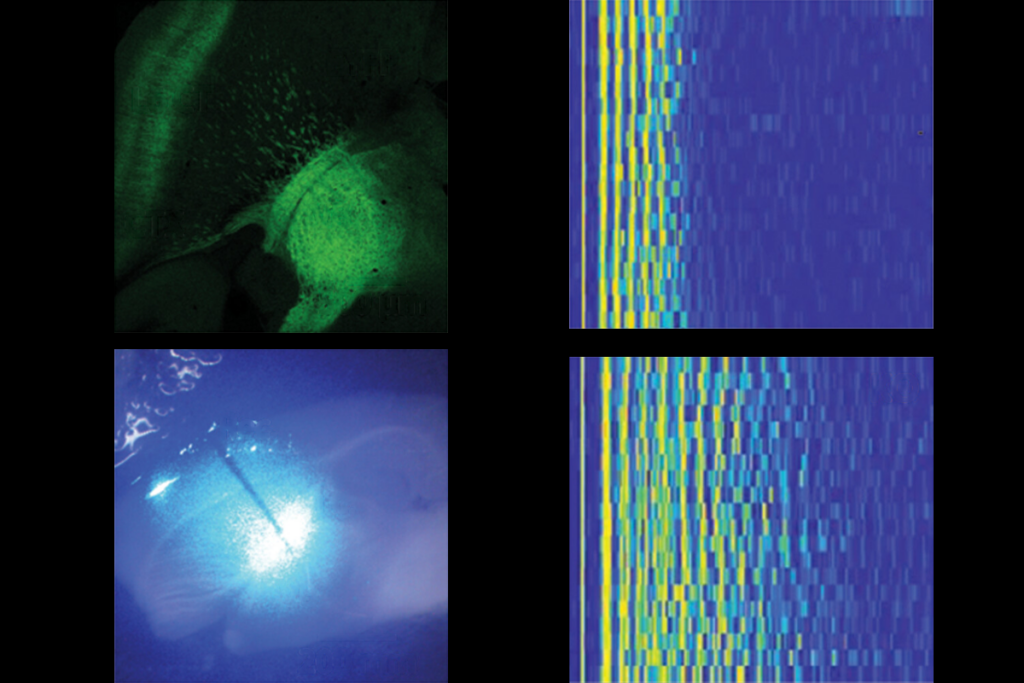

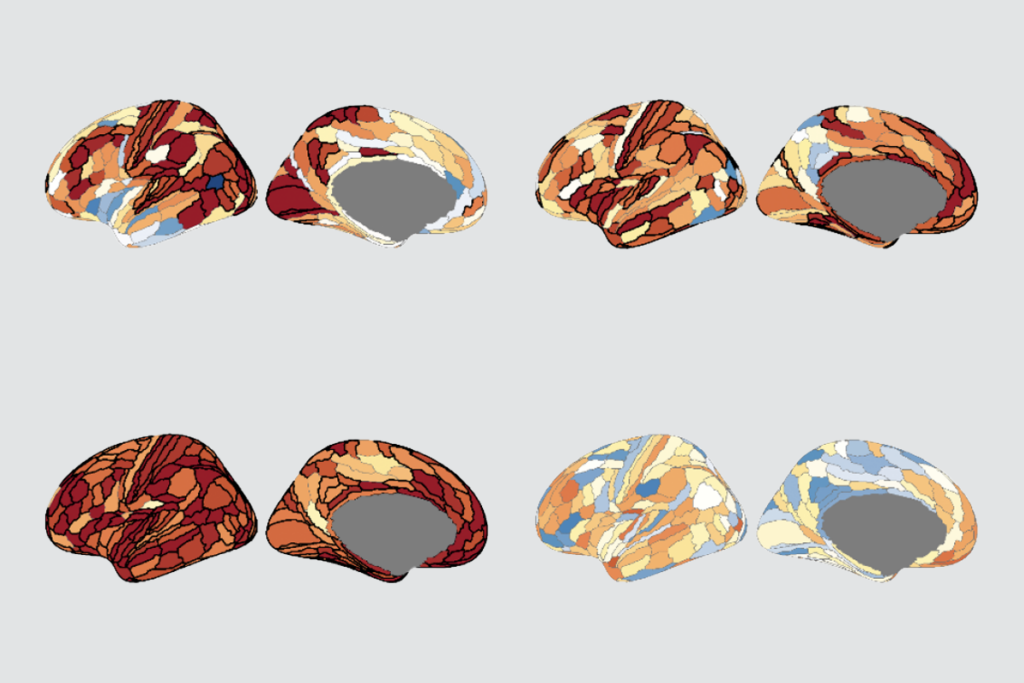

Michael Breakspear and Mac Shine explain how brain processing changes across neural population scales