Bad trip

Hallucinogens like LSD and MDMA may help people with autism become more sociable, but negative side effects argue against their use.

Ecstasy-Article.jpg

Many parents of children with autism would probably be happy to sign their children up for clinical trials of a drug shown to increase friendliness, extroversion, closeness to others and sociability.

But what if that drug were a Schedule 1 controlled substance, considered just as dangerous as heroin and cocaine by the United States Drug Enforcement Agency?

MDMA, popularly known as ecstasy, has long been touted as an ’empathogen’ that enhances social feelings, even when users are sitting soberly in laboratories, not dancing all night under flashing lights in warehouses. A new study testing the effects of MDMA on social cognition in healthy people finds that these reports are not exaggerated, though they are slightly off-kilter.

Participants in the study reported feeling more loving towards other people — and were also less likely to recognize fear and other negative emotions in others. The researchers speculate that rather than making users more empathetic — sensitive to the feelings of others — MDMA may be lessening the impact of negative emotions, thereby promoting social contact. That’s a small but crucial difference, and one that could be very significant if the drug were ever to be tested on people with autism — something the researchers discussed in the wide media coverage of the paper.

Study participants under the influence of MDMA are more likely than those taking either placebo or methamphetamines to classify pictures of faces with distinctly non-neutral expressions like anger or fear as neutral. Given that people with autism generally tend to interpret neutral facial expressions negatively, MDMA might help them make more accurate assessments and, as a consequence, become less socially inhibited.

However, people with autism have also been arrested for exhibiting behavior that others perceive as threatening, even if this is not their intent. So further decreasing their already hampered ability to interpret fear or anxiety in others could place them at risk. An editorial accompanying the article makes precisely this point.

This isn’t the first time a hallucinogen has been proposed as a treatment for autism. In the early 1960s, researchers administered LSD to children with autism aged 6 to 15 in four separate studies, reporting increased alertness, eye contact and physical contact, and decreased anxiety, aggression and stereotypies in many study participants. Others, however, became “completely immobile, preoccupied with objects and showed diminished responsivity and disturbing responses.” The experiments came to an abrupt end when use of the drug was banned in the United States in 1967.

I read about the LSD experiments on a poster at the Society for Neuroscience meeting in San Diego in November.

I asked neuroscientist Pavel Belichenko, who was absorbed in the poster when I arrived, what he thought of it. He shrugged.

“Freud used cocaine to treat his patients,” he said. “In the old days, people could do whatever they liked. Now it’s a completely different story.”

Recommended reading

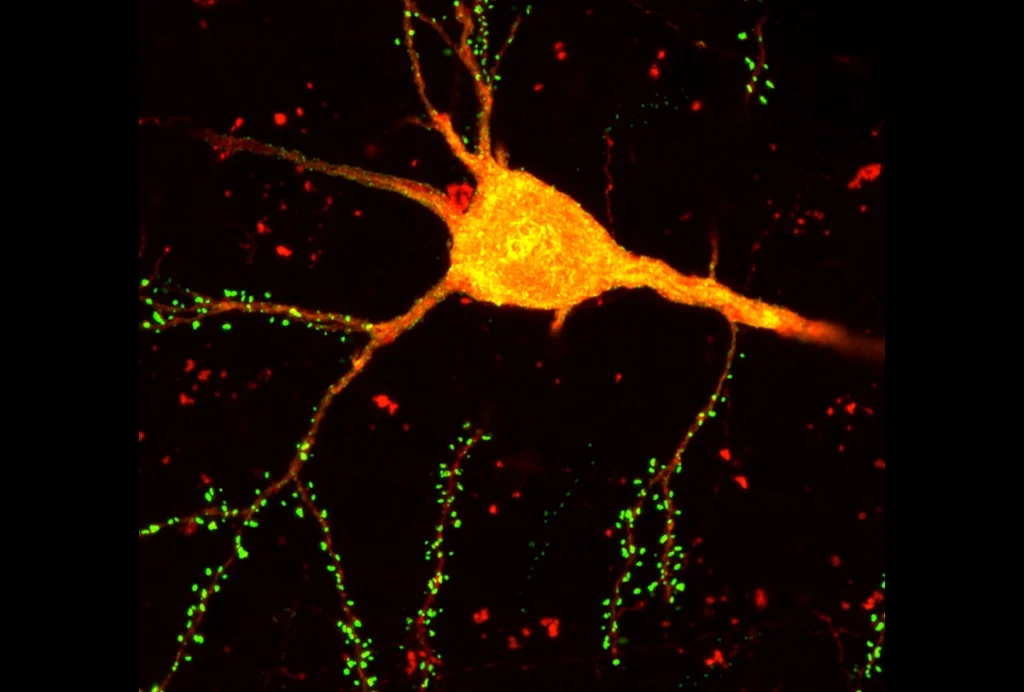

Cerebellum structure; AMPA receptors; MAGEL2 gene

Microglia’s pruning function called into question

Okur-Chung neurodevelopmental syndrome; excess CSF; autistic girls

Explore more from The Transmitter

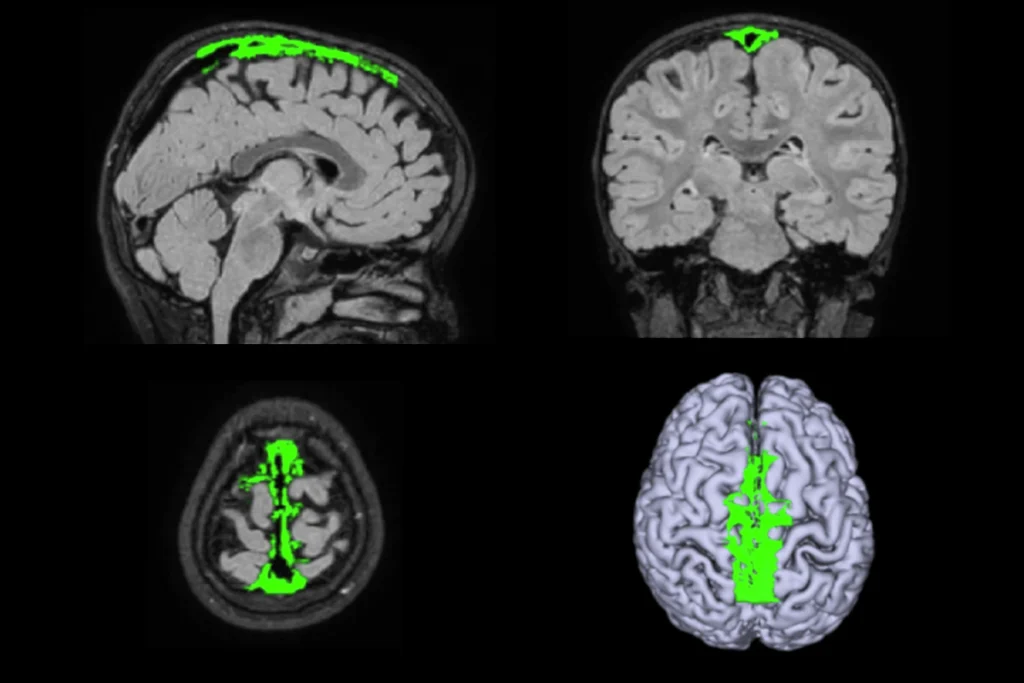

START method assembles brain’s wiring diagram by cell type

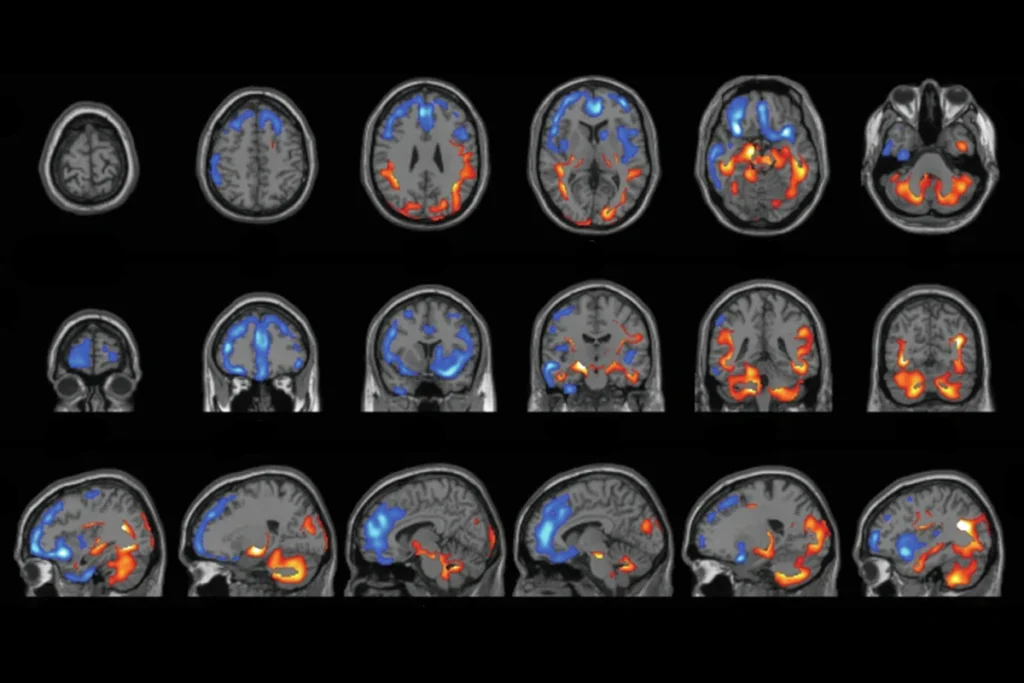

Timing tweak turns trashed fMRI scans into treasure