Autistic people should be valued for their strengths in the workplace

Just 16 percent of adults with autism are in full-time paid employment, and those who do get a job often face discrimination and isolation at work.

Just 16 percent of adults with autism are in full-time paid employment, and this situation is not improving. The Economist has described this as “a tragic toll, as millions of people live idle and isolated outside the world of work.”

When people with autism do get a job, they face bullying, discrimination and isolation in the workplace.

I know the harsh reality from personal experience. Who better to research and write about productivity and employment outcomes than someone who has experienced autism and 40 years of competitive employment?

Autism is a lifelong phenomenon. It’s in the genes. It will never go away.

At school I was called ‘retard,’ ‘crazy horse’ and other stupid names. Even worse, I was expelled eight times. Teachers did not understand that I could not identify nonverbal cues to behavior. That I needed to move and to run to cope. That I spoke loudly and was perfectly clear about my perspective with teachers and peers but could not reciprocate appropriately in school interactions.

I found school tasks based on rote learning very challenging. I had difficulty processing sound information. I could concentrate for long periods on tasks of interest to me but was unable to respond to teacher cues about where to direct my attention. I was punished repeatedly without really knowing why.

But my mother never gave up on me. Time after time she found another school so I could continue my education. Thank you, Mum. You are the greatest.

These school expulsions traumatized me so much that I vowed never to let a workplace terminate me. When a job was not working out, I quit and found another — 28 times in 27 years.

Then, at age 47, I found a job I held for 15 years, until I retired.

These experiences have informed my research into strategies to improve employment rates and work enjoyment for other people with autism.

Focus on strengths:

Mainstream psychiatry frames autism as a spectrum of disorders. Really? Do we have to act like somebody else to be judged ‘normal’?

Laurent Mottron, professor of psychiatry at the University of Montreal, argues against a ‘deficit-based’ approach to children with autism. The premise is that ‘treatment’ should change them, make them conform, suppress their repetitive behaviors and moderate their ‘obsessive’ interests.

This approach, Mottron says, has done nothing to improve employment outcomes for people with autism.

In my own case, attempts by teachers and work managers to make me behave ‘normally’ often just triggered my autism. My reactions at school led to expulsions. At work I would quit.

So I agree with Mottron and other autism researchers that want to move beyond studying autism as a deficit and to emphasize the abilities and strengths of people with it.

Key to productivity:

Part of the economic rationale for funding Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is based on the scheme leading to productivity gains by increasing people’s independence and participation in the workforce. The whole scheme will be compromised if we fail to promote better productivity and employment outcomes for people with autism, who make up 29 percent of participants in the scheme with approved plans.

Research by the Gallup Organization shows that people who use their strengths every day are 8 percent as productive and 15 percent less likely to quit their jobs, six times as likely to be engaged at work, and are three times as likely to report an excellent quality of life.

Performance reviews that emphasize personal strengths improve organizational performance. Singling out people with autism by focusing on their deficits alone does not make sense.

Personal insights:

My academic method is auto-ethnographic — involving deep reflection on my personal experiences over a lifetime of living with autism and connecting this experience to wider cultural, political and social understanding.

Three key insights for enhancing employment outcomes have emerged.

- First, enable strengths. Build on employee knowledge, skills and willingness to engage meaningfully and productively at work.

For example, providing a predictable structure and routine and the chance to contribute and plan for change enabled my strengths as a sales consultant to benefit the organization. Those strengths include being goal-focused, persistent, analytical, logical and free from the restrictions of procedure others took for granted.

- Second, treat every individual as an asset to grow and retain.

This idea builds on the theory of knowledge-worker productivity proposed by Peter Drucker, the father of modern management. An employer can define a worker’s job tasks but should allow the worker to work out how to do a task most efficiently.

In my case, I compensated for a lack of neurotypical social skills by convincing management to give me autonomy because I created value for the business. This strategy proved its worth in my final, and by far longest, period of employment.

- Third, be aware of and avoid autism triggers.

These triggers, however trivial they may seem to others, can set off acute stress reactions. Triggers include unexpected and unexplained changes to routines and expectations, interactions involving implied but ironic criticism, casual off-the-cuff negative feedback, and visual or auditory distraction during periods of stress.

In my final workplace, for example, my managers and I used a mediator to avoid confrontations over work issues that would have been too stressful. As a result, I could circumvent the pressures that had previously led me to resign.

The verdict:

The hallmark of an enlightened society should be its level of inclusion. Wanting to change a person’s autistic behaviors is like attempting to correct left-handedness or sexual preference. It is cruel, unnatural and doomed to fail. It does not foster inclusion but emphasizes exclusion.

We can change the significant social and employment disadvantage experienced by people with autism by seeing their assets rather than their liabilities. By rethinking their management attitudes and practices, workplaces can harness as strengths and advantages the attributes that usually disadvantage people with autism.

This story originally appeared on The Conversation. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum’s style.

![]()

Recommended reading

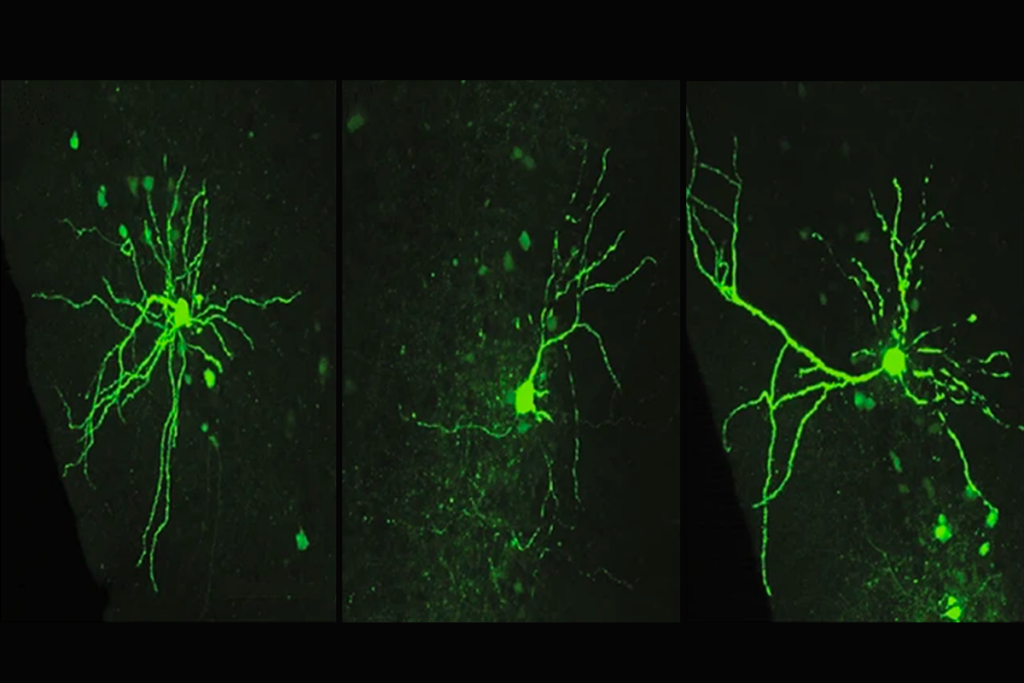

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

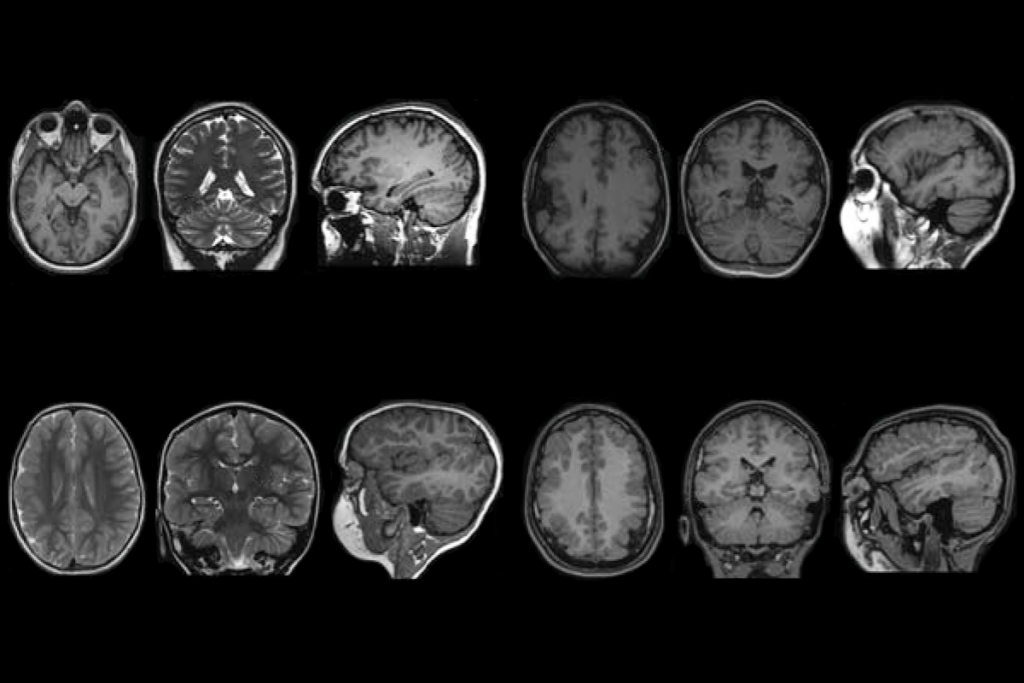

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence