Genes linked to immune function are highly expressed in the brains of autistic people and prenatal boys, according to a new unpublished study presented last week at Neuroscience 2022 in San Diego, California. The findings point to a potential explanation for autism’s male bias, the researchers say.

About four boys are diagnosed with autism for every girl. Clinician bias may account for some of that difference but cannot explain the full gap, says lead investigator Donna Werling, assistant professor of genetics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

It may be that something about male biology “amplifies the impact” of genetic mutations that contribute to autism, she says, “or something about females’ biology that reduces the impact of those risk factors.”

To explore the biology behind autism’s sex bias, Werling and her colleagues assessed how gene expression differs in the male and female brain.

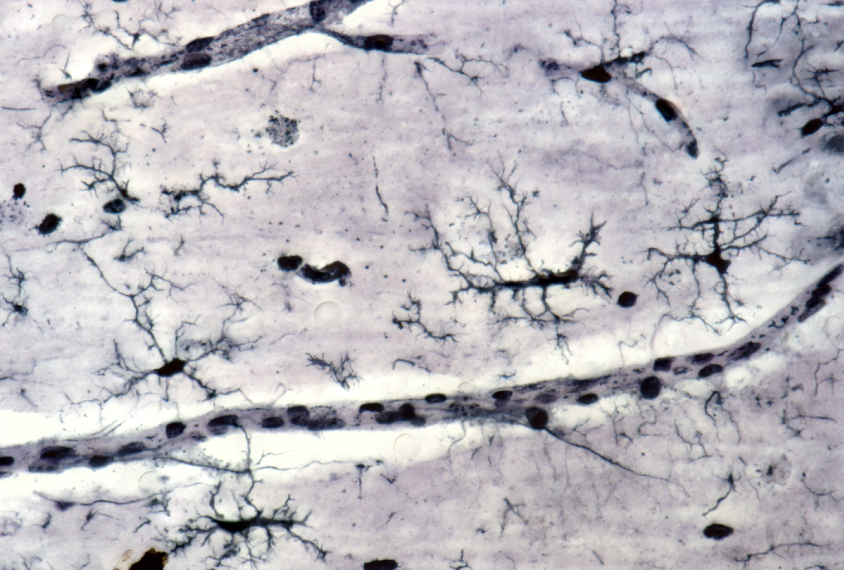

Autism-linked genes are not expressed differently in the male versus female cortex during prenatal development, past work from the group suggests. But of the genes known to be dysregulated in the brains of autistic people, a group of genes associated with astrocytes and microglia — two types of brain cells with ties to immune function — have a large difference in expression based on sex. The new study confirms these findings in the largest dataset examined to date.

“There’s something about the way that those genes work together that seems to be specific to males,” says study investigator Lee Kissel, a graduate student in Werling’s lab who presented the work on 13 November.

T

he team analyzed data from BrainVar, an RNA-sequencing database with expression levels of 15,649 genes from human dorsolateral prefrontal cortical tissue between 14 and 21 weeks post-conception.Looking at data from 39 male and 46 female donors, the researchers found that genes associated with astrocytes and microglia were upregulated prenatal male but not prenatal female brains — a pattern that mirrors the gene expression seen in postmortem brains from autistic people. Although the sex differences are small in magnitude, it suggests that the function of immune cells in the brain “might be something that mediates this intersection of sex-differential biology and autism biology,” Kissel says.

The findings are consistent with the idea that maternal immune activation — an increase in immune signaling during pregnancy, often due to an infection and which some researchers have linked to a higher likelihood of autism in the child — might contribute to autism’s male sex bias, Werling says.

“It seems possible that microglia that are either more prevalent or more prone to an activated state may be more responsive to maternal infection or early-life infection. So if there’s a difference in the reactivity, or just the number of cell types in males and females, that could potentially lead to differences in brain development after that environmental exposure,” she says.

The team plans to evaluate whether these differences hold up in other large datasets. They also plan to analyze data across brain tissue from autistic male and female donors and, if possible, study other periods of development and non-cortical brain regions that are known to have larger sex differences, Kissel says.

“Investigating these other links will give us a better insight into what is going on in the brain when a child develops autism and how sex is shaping those processes,” Werling says.

Read more reports from Neuroscience 2022.