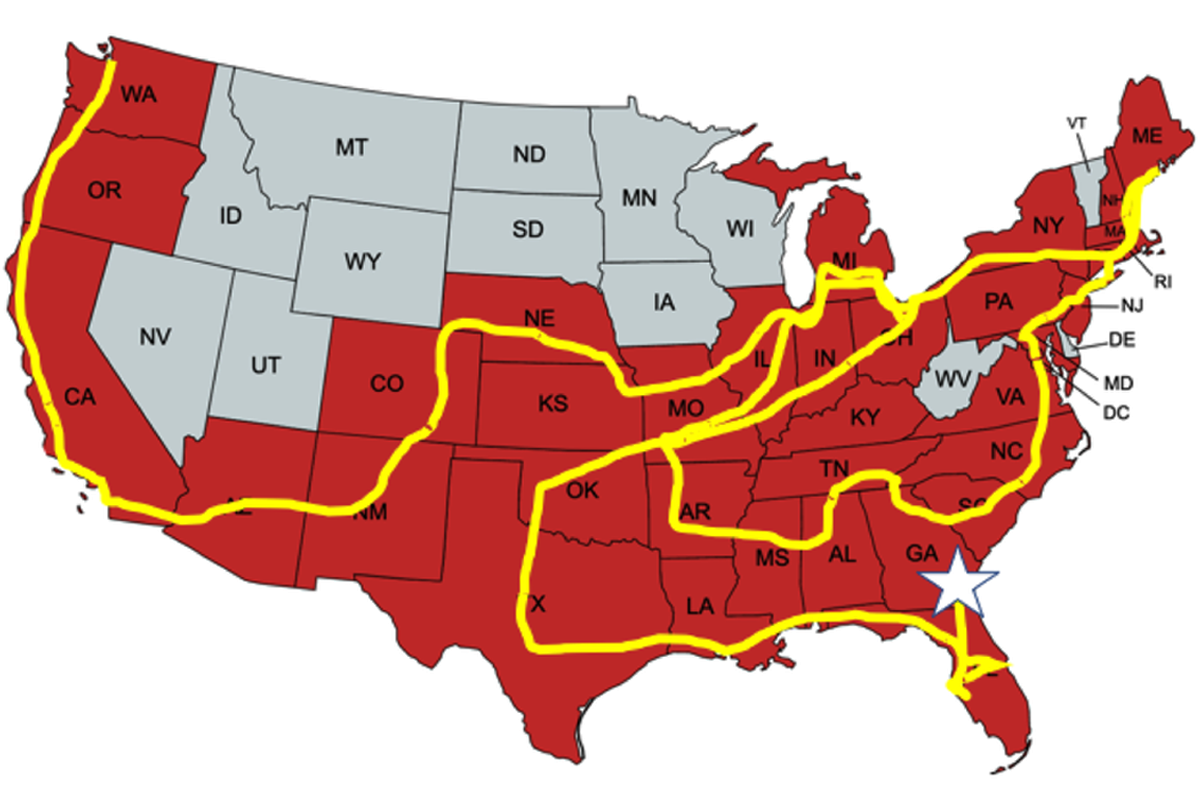

Hudac, now associate professor of psychology at the University of South Carolina in Columbia, is one of a growing number of researchers who are taking their research on the road to improve diversity and inclusion in autism research — which is overwhelmingly skewed toward white and affluent autistic children who have low-support needs and can more readily travel to a lab. As part of that itinerary, these scientists are adapting experimental protocols and partnering with marginalized communities.

Some of this work is already paying off: One autism project increased its proportion of participants from underrepresented ethnicities by up to 3 percent after offering home visits to collect saliva samples, according to results presented late last year at a conference.

Such gains, though still small, are critically needed, says Brian Boyd, distinguished professor of education at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “Having research samples that are more representative and reflective of the broader autism population will enhance our understanding of autism.”

Home visits often demand more resources than do traditional lab assessments. Researchers must manage scientific goals while being flexible when collecting data from participants with complex issues and social-communication difficulties. But, Hudac says, home visits are here to stay. “That’s a new forever thing for us.”

F

or decades, the overwhelming majority of autism research has focused on people of European ancestry and those from relatively affluent communities or with mild traits, who typically live nearer to major research centers or can travel there more easily than those from lower socioeconomic communities or with severe traits.

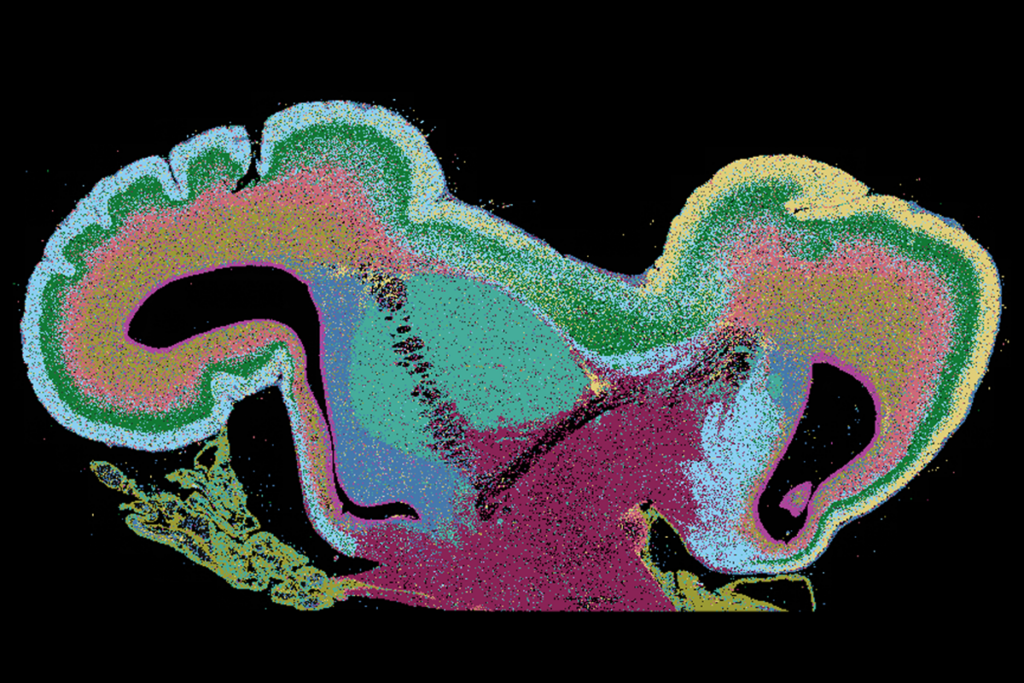

“Our lab-based studies are 80 percent white, high-education and high-income [families],” says Lauren Schmitt, assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati in Ohio, who uses EEG to probe the neural basis of fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited form of autism; children with fragile X also have varying levels of intellectual disability. “It makes sense, because you have to take four or five hours off of work to come and participate, and we don’t pay a huge amount for [participating in] these studies,” she says.

Like Hudac, Schmitt has been piloting home visits to conduct tablet-based cognitive assessments and collect blood samples and EEG data from a broader range of participants than can visit her lab. Her goal is to understand how levels of the FMRP protein, which is lacking in people with fragile X, influence brain activity.

“We want to capture the full fragile X phenotype by reaching these families in their homes if their kids have irritability or high anxiety, but also if they just can’t take time out of their day to get [to the lab],” Schmitt says.

Home assessments are similarly helping researchers to collect data from children who speak few or no words. Minimally verbal children produce twice as many utterances, and more varied utterances, when prompted in a familiar setting — for example, by their parents during everyday activities at home — than they do with trained examiners in the lab, according to a 2020 study.

“That was way higher than we might have expected,” says Helen Tager-Flusberg, director of the Center for Autism Research Excellence at Boston University in Massachusetts, who led the work.

Home is a more comfortable environment for the child, says Karen Chenausky, director of the Speech in Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders Lab at the Massachusetts General Hospital Institute of Health Professions in Boston. Chenausky didn’t take part in the study but has worked with Tager-Flusberg on other studies of minimally verbal children with autism.

Chenausky’s team, for example, has used Zoom to film minimally verbal and low-verbal children as they watch a YouTube video of their choice at home. Measuring the children’s facial movements and comparing them with those of non-autistic children or autistic children with typical speech and language abilities could reveal whether their motor systems differ, she says.

Unlike taking a traditional language assessment, watching a video is a task that autistic children with language difficulties can perform successfully, Chenausky adds. “It’s our way of potentially including everyone in language studies, even kids who don’t talk.”

H

ome visits may have the potential to reach a broader participant pool, but they present a variety of challenges for collecting data. For instance, things such as barking dogs can render portions of video or EEG recordings unusable, and without a partner, EEG caps can be difficult to place accurately over curly or Afro-textured hair.

Data collection at home requires researchers to be flexible yet rigorous, says Carol Wilkinson, assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School. Too strict, and the results may not be generalizable to many people. Too lax, and the science suffers. “We’re figuring out what’s the happy medium,” says Wilkinson, who is collecting EEG data in primary care clinics but hopes to one day collect data in participants’ homes.