Autism research funding rises but still falls short of goals

Federal funding for autism research increased by $23.2 million from 2016 to 2018, according to the latest report from the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee.

U.S. federal funding for autism research increased by more than $23 million from 2016 to 2018, according to the latest government report. But the increases lag behind the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee’s (IACC) goal of doubling the 2015 research budget by 2020.

The committee is the federal government’s primary means of overseeing autism research funding. It reports to the Office of Autism Research Coordination (OARC), which generates funding summaries to guide IACC every two years. Traditionally, IACC meets twice each year to also gather expert commentary before making recommendations to the secretary of health and human services.

The committee has not met since July 2019 and has yet to announce new members, but OARC released its latest report in April.

Autism research funding has increased by 74 percent since IACC first began tracking it in 2008, the report shows. But some members of Congress are asking for an additional $150 million in funding in 2022, to better align with IACC’s recommendations.

The vast majority of money spent in 2017 and 2018, the report shows, supported projects in seven priority areas that IACC identified more than a decade ago: screening for and diagnosing autism; the condition’s underlying biology; factors that contribute to autism; treatments and interventions; services for autistic people; support for autistic teenagers and adults, known as ‘lifespan issues’; and collecting and distributing research data about autistic people.

“It is encouraging to note that the area with the smallest number of projects, research on lifespan issues, has also grown during this time,” says Susan Daniels, OARC director and IACC’s executive secretary.

The report also evaluated research dollars spent in two key areas: autism in women and girls, and, for the first time, racial, ethnic, geographic and socioeconomic disparities in autism.

Misaligned priorities:

The committee examined funding from 9 government agencies and 14 private funders. (One private funder, the Simons Foundation, is Spectrum’s parent organization.) The 23 groups reported a total of about $373 million spent on autism research in 2017 and nearly $388 million in 2018, compared with about $364 million in 2016. The National Institutes of Health provided roughly two-thirds of the total funds in both years.

IACC had recommended spending considerably more — $452 million in 2017 and $519 million in 2018 — to reach its goal of $685 million in 2020, or double its 2015 budget. Funding from 2019 and 2020 has not been analyzed yet, but the 2020 goal, which Daniels describes as “very ambitious,” may still be met on a delayed timeline.

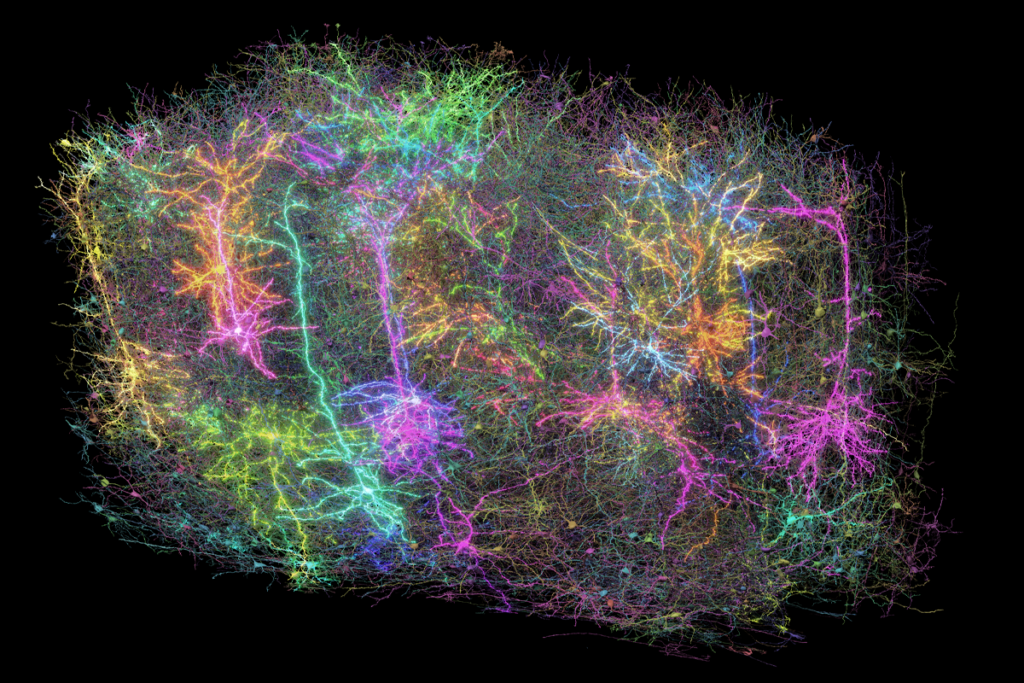

As in past years, the largest portion of funds — 38 percent in 2017 and 42 percent in 2018 — supported research on autism’s biology, whereas the smallest — 9 percent in 2017 and 10 percent in 2018 — covered lifespan issues and services. That balance also held true for the number of research projects.

The distribution doesn’t align with the autism community’s long-held priorities, says Sam Crane, legal director of the Autistic Self Advocacy Network (ASAN) and a former IACC member.

“It’s just a shockingly low level of funding,” Crane says. “As long as these reports have been issued, we’ve been really alarmed by the underfunding of these two areas.”

New focuses:

Even lower percentages of the total funds went toward the two special focus areas the report considered.

Researchers spent $7.1 million, or 1.9 percent of funding, on projects devoted specifically to autism in women and girls in 2017 and $5.1 million, or 1.3 percent, in 2018. They spent $21.3 million on research on racial, ethnic, geographic and socioeconomic disparities in 2017 and $23.4 million in 2018, accounting for 6 percent of the total funds in each year.

Addressing such disparities has been a goal since IACC laid out its first strategic plan in 2009, Daniels says, but “with racial disparities and health equity recently becoming topics of increased national focus, it seemed like an opportune time to do this analysis.”

The reports are crucial for IACC’s recommendation process and for groups such as ASAN, Crane says. She says she wishes OARC had the resources to produce them faster — the 2017 data, for example, are already four years old.

“If we see things that we’re concerned about in the trends, it’s hard to tell whether those trends are continuing or if this is just something that happened four years ago,” Crane says. “So it’ll be hard to necessarily connect it to policy.”

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

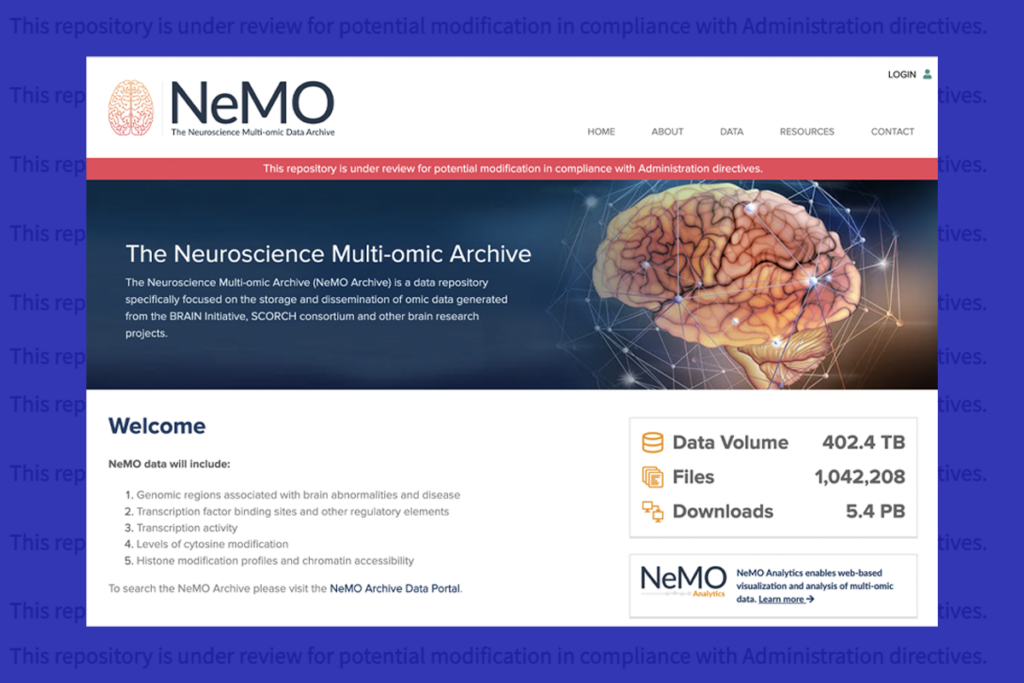

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors