Autism research expected to prosper under Obama

At the height of his presidential campaign against Senator John McCain last July, Barack Obama declined the advocacy group Autism Society of Americaʼs invitation to discuss health reform at a town hall meeting. But in a written response, the then-Senator promised to increase federal funding for autism research and treatment to $1 billion each year by the end of his first term in office.

At the height of his presidential campaign against Senator John McCain last July, Barack Obama declined the advocacy group Autism Society of Americaʼs invitation to discuss health reform at a town hall meeting. But in a written response, the then-Senator promised to increase federal funding for autism research and treatment to $1 billion each year by the end of his first term in office.

Less than two weeks after Obama took the presidential oath, autism researchers are pleased with his outspoken focus on science including, notably, an economic stimulus package that, if accepted by Congress, would dole out $2.5 billion for research at the National Science Foundation and $3.5 billion for research and building maintenance at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Autism is the only disease or disorder specifically mentioned in the presidential agenda published on the new White House website.

“I think that the attitude towards science, and the importance of getting evidence and doing research, will be more valued [under Obama],” says Cathy Lord, director of the University of Michigan Autism & Communication Disorders Center.

“The focus may shift somewhat to say to the scientists, ‘What do you think is important?ʼ And then, ‘How do we accumulate knowledge that’s going to specifically affect health and autism?ʼ” Lord adds.

On his official campaign website, Obama had promised to appoint an ‘autism czar’ who would oversee research on autism, eliminate bureaucracy, and coordinate autism-related agencies at state and local levels. The website added that Obama would fully fund the 2006 Combating Autism Act, which earmarked nearly $1 billion in autism-related federal funding over five years.

The new president has not yet chosen a new director of the NIH, nor addressed any of these campaign promises. Still, scientists are hopeful he will keep his word.

“I’m very optimistic, just like most of America is,” says Dan Geschwind, professor of neurology and psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine. “I’m sure there’s going to be some influx of money over the next few years to support health initiatives, and that will hopefully extend to mental health.”

Science’s rightful place:

In Obama’s inaugural address he said, between bouts of applause, “We will restore science to its rightful place.”

This attitude is a departure from his predecessor, George W. Bush, who waited nearly eleven months before choosing the members of his President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology (PCAST), the non-government team of experts that counsels the president at his discretion. Bush’s PCAST, made up of mostly technology industry representatives, met 22 times between June 2002 and September 2008, and only 5 times with the president.

PCAST is supposed to be “keyed to issues where the president thinks he needs some advice,” says Kei Koizumi, director of the R&D Budget and Policy Program at the American Association for the Advancement of Science. “[But] there’s certainly a strong perception that President Bush didn’t listen.”

Obama announced the new co-chairs of his PCAST in December, even before he took office. The co-chairs are both eminent biomedical researchers: Eric Lander, one of the leaders of the Human Genome Project and member of the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research in Cambridge; and Harold Varmus, former NIH director, Nobel Laureate, and head of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer in New York City.

“They will work to remake PCAST into a vigorous external advisory council that will shape my thinking on scientific aspects of my policy priorities,” Obama said.

Scientists are eagerly awaiting the presidentʼs pick for director of the NIH, which funds the bulk of autism research in the U.S; in 2008, the NIH devoted $118 million to autism research. Francis Collins, former director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, is the rumored front-runner for the position, but has so far declined to comment on the matter.

Tom Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, and Judith Cooper, director of the Division of Scientific Programs at the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, both declined to comment on the future of autism research under the new president. “A lot of the policy will depend on what the new [NIH] director would like to do,” says Koizumi.

Last August, Obama told ScienceDebate 2008 ― a group of hundreds of prominent scientists, business leaders, and policy makers ― that his administration would “increase funding for basic research in physical and life sciences, mathematics, and engineering at a rate that would double basic research budgets over the next decade.”

“I think that there will be more money flowing into NIH and hopefully it will at least bring us back to where we were,” says Geschwind, whose lab receives about $8.2 million in NIH funding. The NIHʼs budget famously doubled between 1998 and 2003, when Varmus was director; Bush vetoed all subsequent proposals for NIH budget increases. “There’s a lot of catch up we have to do now,” Geschwind says.

Others note that there are limits on the extent to which politicians, even the president, can dictate scientific research.

“If a [chief] executive says today, ‘We want to do research on A or B or Cʼ, if there are no investigators to do it, and they don’t produce proposals that pass peer review, it wont get done,” says Roy Richard Grinker, professor of anthropology at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., and a self-described Obama supporter.

Political enterprise:

Last April, at a campaign rally in Pennsylvania, someone in the large crowd asked Obama about the autism epidemic in America. “Autism is an area where our basic investment, our basic research has to increase,” Obama responded. “We’ve seen just a skyrocketing autism rate. Some people are suspicious that it’s connected to the vaccines ― this person included,” he added. “The science right now is inconclusive, but we have to research it.”

A few hours after these remarks had been disseminated ― with much fanfare ― in the press, a campaign spokesperson clarified that Obama had pointed to a person in the crowd, and was not referring to himself, when he said “This person included.”

Still, the incident left some researchers questioning Obama’s grasp of, and respect for, science. “I was a little taken aback and worried,” says Grinker, who has studied the epidemiology of autism. The science on autism and vaccines, Grinker says, “is as conclusive as science can be.”

Dozens of large epidemiological studies have shown that there is no link between vaccines and the rising number of autism diagnoses in the past two decades. In 2004, after reviewing more than 200 scientific studies, the U.S. Institute of Medicine dismissed any link between autism and vaccines.

Grinker says he also worries that political pressures and “public fear” had a lot to do with the prominent role that autism played in the 2008 campaigns, and particularly with Obamaʼs plans to appoint an autism czar.

“When Barack Obama says that we want to restore science to its ‘rightful place,’” Grinker says, “I [hear] him saying that the democratization of science doesn’t mean that science should be a political enterprise.”

Obama has a long history of paying attention to autism, however. In December 2007, for instance, he taped a video outlining some of his plans for helping Americans with autism and other disabilities.

“We should screen all infants for the full array of potential impairments and set a national goal to re-screen all 2-year-olds. Some conditions, like autism, don’t appear until age 2, so infant screening is not enough,” he said.

During his short term in the U.S. Senate, Obama also co-sponsored several bills related to autism, including one that authorized $350 million in federal funding for treatment and services for adults with autism.

On the White House website, these plans for autism are listed in a section about disabilities.

Defining autism as a long-term disability may mean more community housing and public employment options for adults with autism, says parent-advocate Kristina Chew, autism editor of Change.org, an online network dedicated to social change.

“He obviously has a focus on screening for young children, and [on] research, but he’s also started to talk about autism in terms of the bigger picture of support services across the lifespan,” Chew says. “Five years ago, I just really didn’t think there were any options.”

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

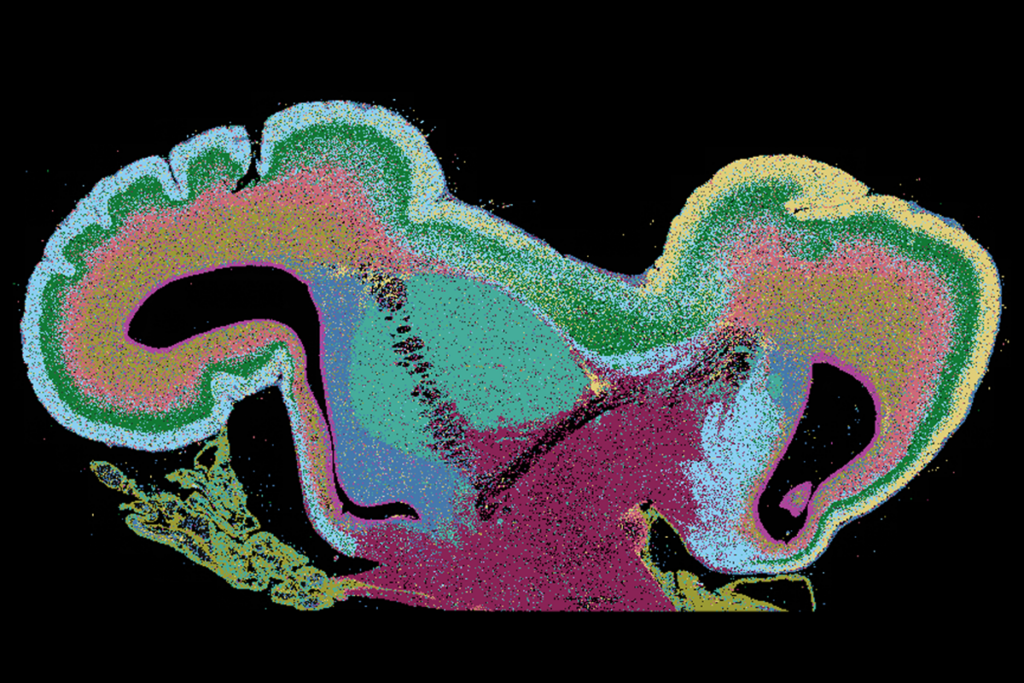

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models