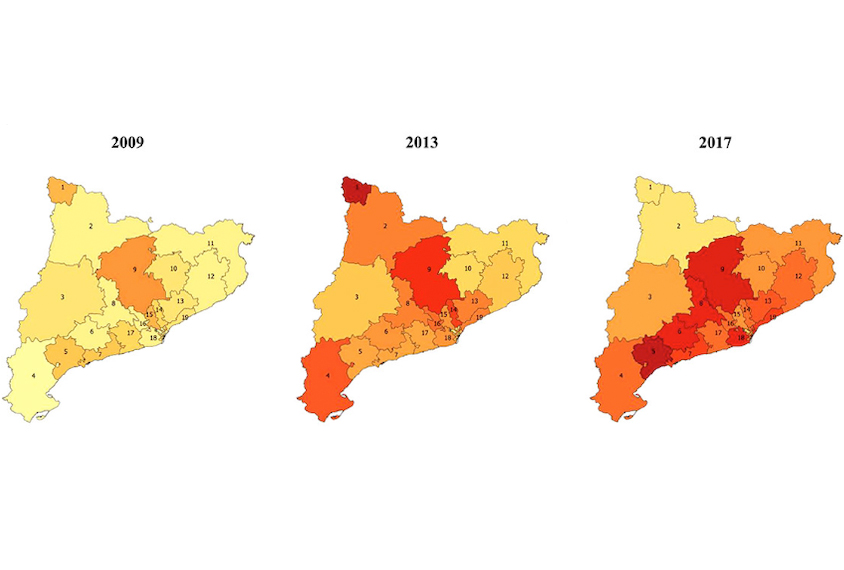

Local variability: The region including Solsonès, Bages and Berguedà counties has the highest prevalence of autism within Catalonia, Spain.

Autism prevalence estimates for Catalonia, Iran highlight gaps in data

The first rigorous estimate of autism in Catalonia, Spain, has found a prevalence on par with that in the United States; an independent study in Iran, meanwhile, has found a prevalence that lags far behind.

The first rigorous estimate of autism in Catalonia, Spain, has found a prevalence on par with that in the United States1. An independent study in Iran, meanwhile, has found a prevalence that lags far behind2.

The most recent reported prevalence in the U.S. is 1 in 40 and is based on 88,530 3- to 17-year-olds.

The reported prevalence in Catalonia, based on about 1.3 million children, was 1 in 81 in 2017 and had steadily risen over the previous nine years, according to the new study. In Iran, the reported prevalence is 1 in 1,000 and is based on 31,000 children.

The Iran team also set out to identify the prevalence of several conditions that often co-occur with autism, such as intellectual disability and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The Catalonia study focused only on autism.

“A weakness of the [Catalonia] study is lack of information on co-occurring conditions such as intellectual disability, and information about sociodemographic variables,” says Maureen Durkin, professor of population health sciences and pediatrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, who was not involved in either study.

The team did chart prevalence over several years, however. They found that the proportion of diagnosed 2- to 17-year-olds rose from 0.07 percent in 2009 to 0.23 percent in 2017. In that final year, the sex ratio for autism diagnosis was roughly 4.5 boys for every girl. The study appeared in November in Autism Research.

The team also mapped autism prevalence geographically to establish a baseline for examining the relationship between environmental pollutants and autism. “In the process of getting the data and starting to set up the study, we thought it would be very relevant to do a first study,” says lead investigator Mònica Guxens, associate research professor at the Barcelona Institute for Global Health.

Early days:

The Iran team conducted informational and diagnostic interviews with 6- to 18-year-olds and their mothers. They found two boys were diagnosed with autism for every girl, but they saw no significant differences in prevalence for demographic variables such as parental education or urban versus rural residence — two factors that have skewed autism prevalence figures in U.S. studies.

They found that 86 percent of autistic children have at least one co-occurring condition: 70.3 percent have intellectual disability, 29.7 percent have epilepsy, 27 percent have problems with bladder control and 21.6 percent have ADHD. The study appeared in October in Archives of Iranian Medicine.

The Iranian team reported that mental health conditions such as schizoid personality disorder in the mother are associated with autism in the child. But Durkin says the lack of information about the father’s mental health raises questions.

“This makes the paper read almost like a mother-blaming study from an earlier era,” she says.

The researchers also used a diagnostic tool that has “low agreement with autism diagnoses based on gold-standard tools,” Durkin says, which may explain the low prevalence they found. The tool, the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Aged Children – Present and Lifetime, is reliable for diagnosing many psychiatric conditions, but not autism3.

Information on mental health was available only for mothers because the researchers did not survey fathers, says study-co-investigator Hadi Zarafshan, psychiatry and psychology researcher at Tehran University of Medical Sciences in Iran. And the team chose this tool because the study was part of an effort to investigate a range of psychiatric conditions — not just autism, he says.

Complementary strengths:

The reported rates of intellectual disability and epilepsy among autistic people in Iran are unusually high. The researchers may have found only the most severe cases of autism, which might further explain their low prevalence estimate, researchers say.

“[It] probably isn’t doing as great of a job at picking up less severe cases,” says Brian Lee, associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at Drexel University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, who was not involved in either study.

Lee notes that his team’s previous work on a Swedish population showed an intellectual disability prevalence of 25.6 percent among autistic individuals4. “And because there is no good reason to suggest that the [autism] rate is different between geographic regions, I would think there is significant underdiagnosis,” he says.

Despite the caveats, the Iran study is valuable, he and Durkin say.

The study begins to fill gaps in information about autism prevalence in a country where, Durkin says, “the challenges of case ascertainment and absence of existing data systems” have created obstacles for researchers.

References:

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

During decision-making, brain shows multiple distinct subtypes of activity

Basic pain research ‘is not working’: Q&A with Steven Prescott and Stéphanie Ratté