Autism mutation alters balance of gut bacteria in mice

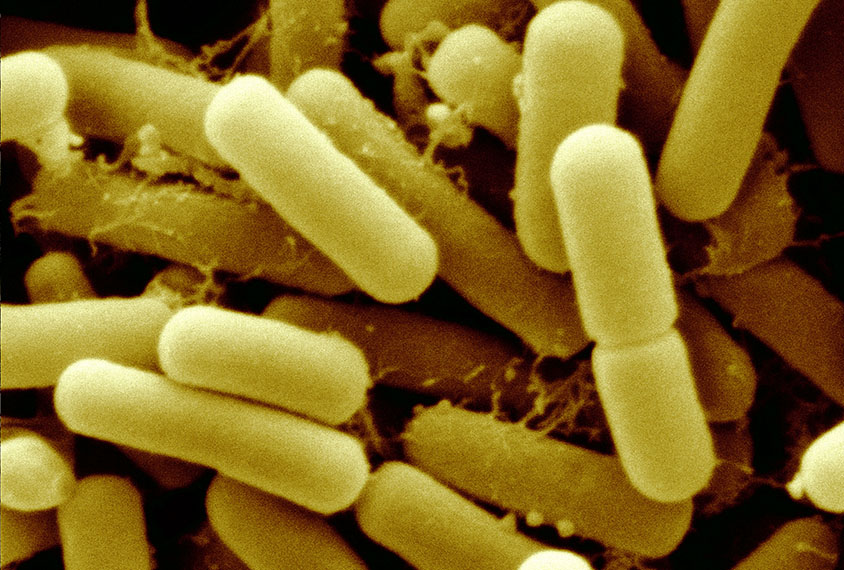

Mice with a mutation in a top autism gene may have altered levels of certain gut bacteria; feeding the mice one of these bacterial species eases some of their troubles.

Mice with a mutation in a top autism gene called SHANK3 have altered levels of certain gut bacteria, a new study shows1. Feeding the mice Lactobacillus reuteri, a microbe found in yogurt and probiotics, eases some of their troubles.

Preliminary evidence suggests people with autism also have an altered gut microbiome — the collection of bacteria in their gut. A small study published last year hinted that using bacterial transplants in children with autism can ease their digestive woes and even their social problems.

The new findings offer fresh evidence to support this idea. They also reveal a connection between autism genes and gut flora.

“I think it’s important to step back and look at how the genetics of autism itself could perhaps change the microbiome,” says lead researcher Evan Elliott, assistant professor of molecular and behavioral neuroscience at Bar-Ilan university in Israel.

The work also hints at an explanation for how bacteria affect behavior: through a chemical messenger called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).

The study is notable because it links genetic and environmental contributors to autism, says Sarkis Mazmanian, professor of microbiology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, who was not involved in the study.

Microbial meal:

SHANK3 mutations account for roughly 2 percent of autism. Elliott and his colleagues looked at stool samples from 31 mice with a SHANK3 mutation and 27 controls.

The mutant mice have less diversity in their microbiome than controls do, the researchers found. Some mice lack certain bacterial species entirely and have diminished levels of others, including L. reuteri. Levels of two bacterial species, from the genus Veillonella, are also unusually low in the female mutants, and one of these is unusually abundant in male mutants.

A 2016 study found that L. reuteri restores social behaviors in mice born with an imbalanced microbiome.

In the new study, L. reuteri also boosts male mice’s — but not females’ interest in other mice. Feeding the mutant mice the bacterium also decreases the number of marbles they bury — a test of the mice’s repetitive behavior.

Still, the relevance of these findings to people with autism is not clear, says Jill Silverman, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute, who was not involved in the study. The mutants are generally sluggish, which can skew the results of the tests, she says.

The work appeared 19 May in Brain Behavior and Immunity.

Chemical connection:

The researchers also investigated how the bacteria might affect behavior. A 2011 study reported that feeding mice another species of Lactobacillus alters expression in the brain of receptors for GABA2. The bacteria secrete fat molecules with a chemical structure similar to that of GABA, and this may alter the expression of the receptors through a feedback loop, Elliott says.

Elliott’s team explored the GABA connection further, measuring levels of L. reuteri and the expression of brain GABA receptors in the mutants.

They found that levels of the gut bacteria track with those of three types of GABA receptors in the brain. Feeding the mice L. reuteri increases the expression of all three types of receptors.

SHANK3 is expressed in neurons in the gut and might alter the microbiome through these neurons, Elliott says. Alternatively, it may alter levels of certain hormones that affect the gut.

Elliott and his colleagues are assessing microbial diversity in the guts of people with autism who carry certain mutations.

References:

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Explore more from The Transmitter

During decision-making, brain shows multiple distinct subtypes of activity

Basic pain research ‘is not working’: Q&A with Steven Prescott and Stéphanie Ratté