Briefly suppressing an overactive signaling pathway in juvenile mice that have an autism-linked mutation blocks them from developing some autism-like traits later, according to a new study. The findings help refine the exact timing of this “critical period” for intervention, the researchers say, and have implications for therapies in people.

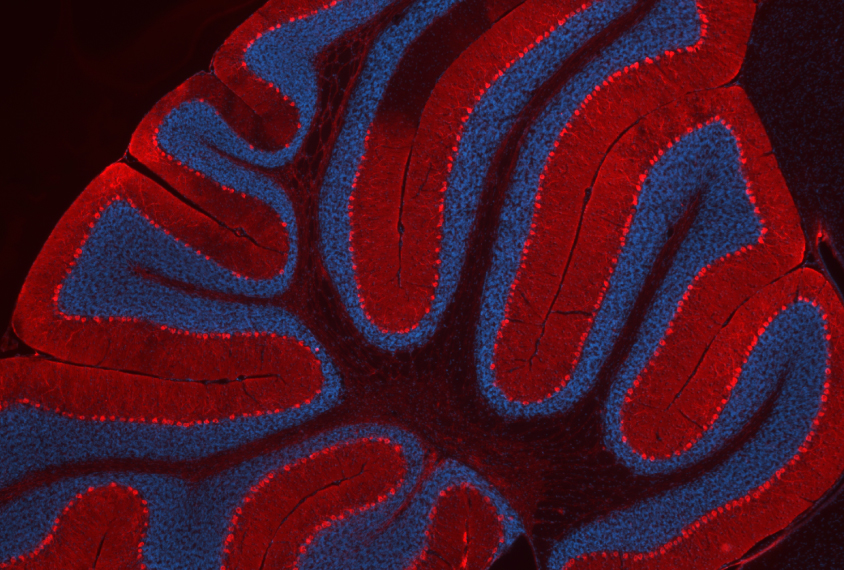

The mice are missing a copy of TSC1 in their Purkinje cells, a type of neuron found in the cerebellum, a brain region involved in movement, cognition and social skills. Mutations in this gene over-activate a signaling pathway called mTOR and cause tuberous sclerosis complex, a condition often accompanied by autism.

TSC1 mice show autism-like traits, such as repetitive behaviors and changes in social interest, the researchers reported in 2012. Treating them with the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin starting at 6 weeks of age — but not at 10 weeks — prevents or reverses those traits, the team found in a 2018 study, hinting at a “sensitive period” during which the brain can respond to interventions.

In the new work, the mice again started rapamycin treatment at 7 days of age; four weeks after treatment stopped, they had typical social and motor behaviors, suggesting they were no longer susceptible to some of the mutation’s effects.

“We’re taking off the medicine, and that’s allowing the gene abnormality to rear its head, but that’s not enough” for the animals to develop autism-like traits, says lead investigator Peter Tsai, assistant professor of neurology at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas. “It suggests the gene is no longer having a critical role for those functionalities.”

Rapamycin, which is already approved as an immunosuppressant for transplant recipients, is in clinical trials in infants with tuberous sclerosis. But its immunosuppression, as well as other side effects, make it less than ideal for long-term use in children, Tsai says.

The new work hints at a period beyond which TSC1 mice no longer require rapamycin — which suggests that people with tuberous sclerosis could benefit from taking the drug for only a short time, he says.

T

he researchers injected the TSC1 mice with rapamycin three times a week during the four- or eight-week treatment periods. The mice took a battery of behavioral tests four weeks after stopping treatment — more than enough time for the drug to stop suppressing mTOR, Tsai says.Untreated TSC1 mice gave little attention to an unfamiliar mouse, which suggested diminished social interest. But four weeks after finishing treatment, treated TSC1 mice had social behavior similar to that of wildtype mice, whether they’d received the drug for four or eight weeks. Treatment for both time periods also blocked motor difficulties from developing.

The drug did not improve the animals’ repetitive grooming or learning challenges, however, suggesting different brain circuits are at play in those behaviors versus the social and motor ones, Tsai says.

Mice with the mutation also have fewer and less-active Purkinje cells. But the cells’ numbers and activity levels rebounded four weeks after finishing either four or eight weeks of treatment.

The results were published in the Journal of Neuroscience on 21 February.

A

lthough it’s unclear exactly what role the cerebellum plays in the animals’ traits, the findings suggest the region interacts with many others to affect behavior, says Matthew Mosconi, director of the Kansas Center for Autism Research and Training, who was not involved in the work.“Just by targeting this one focused part of the brain, you’re potentially impacting multiple behaviors during an important period of development,” he says.

The results echo findings that disrupting activity in the cerebellum in juvenile, but not adult, mice can lead to autism-like social behaviors, says Samuel Wang, professor of molecular biology at Princeton University, who led that work but was not involved in the new study.

“The concept of a critical period for the development of social behavior is interesting,” Wang wrote in an email to Spectrum. “I am glad to see the Tsai lab report a confirmation of our results.”

Tsai’s 2018 study showed that treatment can be effective at a later age, but the new work suggests that if treatment starts early enough, it may not have to be given long-term, Mosconi says. Both findings are important given the reality that some people with tuberous sclerosis — and those with other forms of autism — are not diagnosed until later in childhood or adulthood.

“It’s really cool and important and impactful,” Mosconi says. “If there is a potential window during which these therapeutics could resolve some of the neurodevelopmental issues and then no longer be needed beyond this certain time window, that could really help.”

Tsai says he next hopes to investigate how the circuits involved in social and repetitive behaviors differ, and to probe the mechanisms that underlie the closing of the circuits’ critical periods of development.