Autism-linked protein differs in male and female brains

The autism-linked protein MET is expressed at lower levels in the brains of men with autism than in control brains, according to unpublished research presented Thursday at the Salk Institute, Fondation IPSEN and Nature Symposium on Biological Complexity in La Jolla, California. Women with autism do not differ from healthy controls, however.

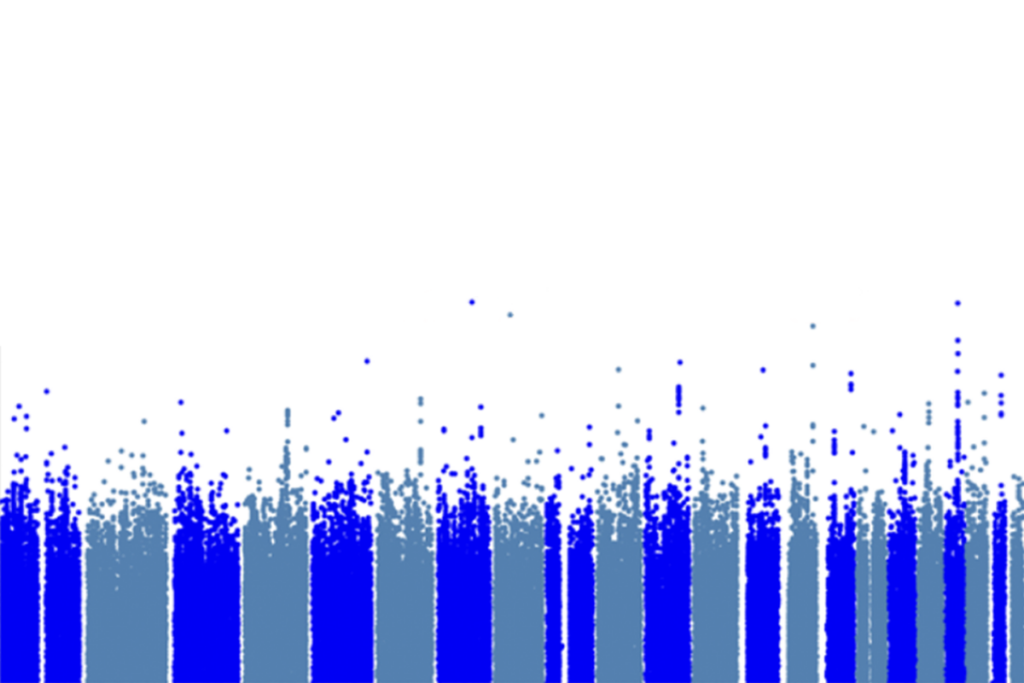

- Pink brain, blue brain: A protein involved in forming connections in the brain is found at different levels in men and women with autism.

The autism-linked protein MET is expressed at lower levels in the brains of men with autism than in control brains, but women with autism do not differ from healthy controls, according to unpublished research presented Thursday at the Salk Institute, Fondation IPSEN and Nature Symposium on Biological Complexity in La Jolla, California.

MET is involved in immune and gut regulation, and in the migration of neurons and formation of synapses, the junctions between neurons. The new study found evidence that MET is regulated by MeCP2, the gene that is mutated in individuals with Rett syndrome.

Researchers have begun to probe differences in gene expression in the brains of healthy men and women1, but this is the first study to report differences between men and women with autism.

“I think people just haven’t looked,” says Jasmine Plummer, a postdoctoral researcher in Pat Levitt’s laboratory at the University of Southern California who presented the work. “In most cases we just pool our data.”

That’s because studies of brain gene expression usually rely on postmortem tissue, which is scarce. The new study analyzed tissue from 9 men and 6 women with autism.

Plummer did not set out to look for sex differences, but her initial analysis turned up no difference in MET expression between those with autism and controls. She did, however, find lower levels of MET in postmortem tissue from people with Rett syndrome, an autism-linked disorder that primarily affects girls.

“So then I stratified it, thinking maybe it’s a female-specific thing,” Plummer says. “But when we actually tested it, it’s the opposite.”

The researchers also found evidence that MET levels are regulated by MeCP2, providing a direct link between these two autism-linked genes.

“This possibly ties in different autism spectrum disorders,” says Benjamin Philpot, associate professor of cell and molecular physiology at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, who was not involved in the work. “It’s always neat to see a convergence in pathways.”

Studies have found that people with autism are more likely to have one form of the MET gene, called the C allele2. Another form of the gene, the G allele, carries low autism risk. The two versions differ by a single DNA letter in the promoter, the part of the gene to which certain proteins bind to turn the gene on or off.

In the new study, Plummer and her colleagues showed that MeCP2 is one of the proteins that bind the MET promoter and alter levels of the protein.

The mutated version of MeCP2 seen in Rett syndrome lowers MET levels, the researchers found. Puzzlingly, however, the normal version of MeCP2 increases the activity of the autism-linked C form of MET, but not the low-risk G form.

The results provide a reminder that interactions between autism risk genes don’t just involve the proteins these genes code for, says Daniel Geschwind, chair of human genetics at the University of California, Los Angeles, who was not involved in the work. “This means we need to pay more attention to [the genes’] regulatory regions,” he says.

It’s not yet clear how the findings from the new study add up to the differences in MET expression observed in men and women with autism. In 2011, Levitt, Geschwind and their colleagues found evidence that the autism candidate gene FOXP2 regulates MET. Plummer is trying to unravel the full network of regulatory proteins that interact with MET.

For more reports from the Salk Institute, Fondation IPSEN and Nature Symposium on Biological Complexity, please click here.

References:

1: Kang H.J. et al. Nature 478, 483-489 (2011) PubMed

2: Campbell D.B. et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 16834-16839 (2006) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter

Remembering Annette Dolphin, who helped explain gabapentin’s effects