Autism is more heritable in boys than in girls

If boys have greater inherited liability for autism, the female protective effect may not fully explain the sex difference in prevalence.

The diagnostic criteria for autism have evolved several times, in part to recognize a broader range of presentations. But two trends have persisted across studies: a higher prevalence in boys relative to girls and a substantially high heritability. This prevalence difference highlights that sex is one of the most important predictors of autism. It also suggests that the biology underlying this sex ratio could reveal mechanisms of this condition.

Many factors could contribute to the sex difference. For example, the presentation or development of autism traits may vary across sex, or girls and women may be more adept at camouflaging signs of autism. These and other nuances, coupled with biased gender expectations, may delay or reduce the recognition of autism in girls.

Nonetheless, because the etiology of autism is primarily genetic, with about 80 percent heritability, behavioral differences alone are unlikely to account for the observed disparity in prevalence across the sexes. Examining the heritability of autism by sex is therefore important for understanding how genetic factors that lead to autism may affect people differently.

We have developed modeling approaches that allow for sex-specific heritability estimation. Unlike past work, which assumed that both sexes share equal variance in genetic liability—and therefore equal heritability—our results show that autism is 10 to 12 percent more heritable in men and boys than in women and girls.

These findings point to several implications and provide guidance for future research. First, although autism is highly heritable in both sexes, there are measurable sex differences in its heritability. Second, researchers need to account for heritable influences and sex when studying the biology of autism, including in future studies that examine the condition’s severity, co-occurring conditions or age at diagnosis. Simply put, to understand autism’s roots, we need to understand relevant sex differences and whether causes might differ in boys and girls.

W

e used data from one of the world’s most extensive epidemiological registers to examine the relationship of sex to the heritability of autism among sibling and cousin pairs. Our cohort study included 1,047,649 Swedish children, forming 456,832 families.By age 19, some 12,226 people—or 1.17 percent of our cohort—were diagnosed with autism. This group comprised 8,128 boys and 4,098 girls. As in previous research, we observed a high heritability for autism, with 87 percent heritability in boys and 75.7 percent heritability in girls. Higher male heritability persisted even after adjusting for factors such as birth year, gestational age and parental age.

Of course, variables other than additive genetic factors could influence the likelihood of an autism diagnosis. These variables—which we labeled as the “residual,” rather than the narrower term, “environment”—could have greater sway in girls.

The residual could include effects of the physical environment or environmental exposures, cultural differences affecting diagnosis, non-additive genetic factors such as rare or de novo variants, or a distinct presentation of autism in girls. But a series of sensitivity analyses indicated that these factors are unlikely to fully account for the difference in autism prevalence between sexes.

Altogether, our analyses suggest that additive genetic factors account for the majority of variance in autism occurrence and exert greater influence in boys than in girls. This conclusion supports a model in which men and boys are more susceptible to additive genetic influences that predispose people to autism.

O

ur findings align with the idea that there is greater variance of genetic liability for autism in boys. As such, these findings contrast with expected observations for the female protective effect (FPE), a prevailing theory for sex differences in autism prevalence.The FPE generally emphasizes a higher genetic threshold for autism in girls. That theory usually assumes equal variance in genetic liability across sex. Other studies also fail to align with the FPE theory. For example, in a previous population registry study from our group, the children of women with autistic siblings did not show a greater likelihood of autism than the children of men with autistic siblings.

Although our observations do not exclude a female protective effect in autism, they suggest that other mechanisms may also explain sex differences in autism prevalence. For example, future investigations could explore gene-environment interactions that increase male susceptibility. Those factors could play out at the level of hormones, reflect effects of the Y chromosome or involve sex-differential regulatory effects by non-sex chromosomes.

Additionally, an alternative model of higher additive genetic variance in males (GVM) versus females warrants greater consideration. Underpinnings of a potential GVM effect could be explored by identifying autism endophenotypes that are more heritable in boys and emerge early in development, prior to the consolidation of the condition.

Examining alternatives to the FPE’s assumptions of a higher genetic threshold for autism in girls could inform causal factors that explain both the male-skewed sex ratio and the biology leading to autism. Overall, this work substantiates the importance of heritable factors in autism for both boys and girls. At the same time, it highlights the need to incorporate the biology of sex differences in causal models of autism, including when examining how non-genetic factors, either separately or in combination with heritable influences, may contribute to the occurrence of autism.

Given inconsistent evidence for the FPE, the possibility that higher additive genetic variance in boys contributes to the skewed sex ratio in autism should be given greater consideration. In that way, findings can inform future mechanistic studies to refine the assessment of autism likelihood and advance toward personalized targets for intervention.

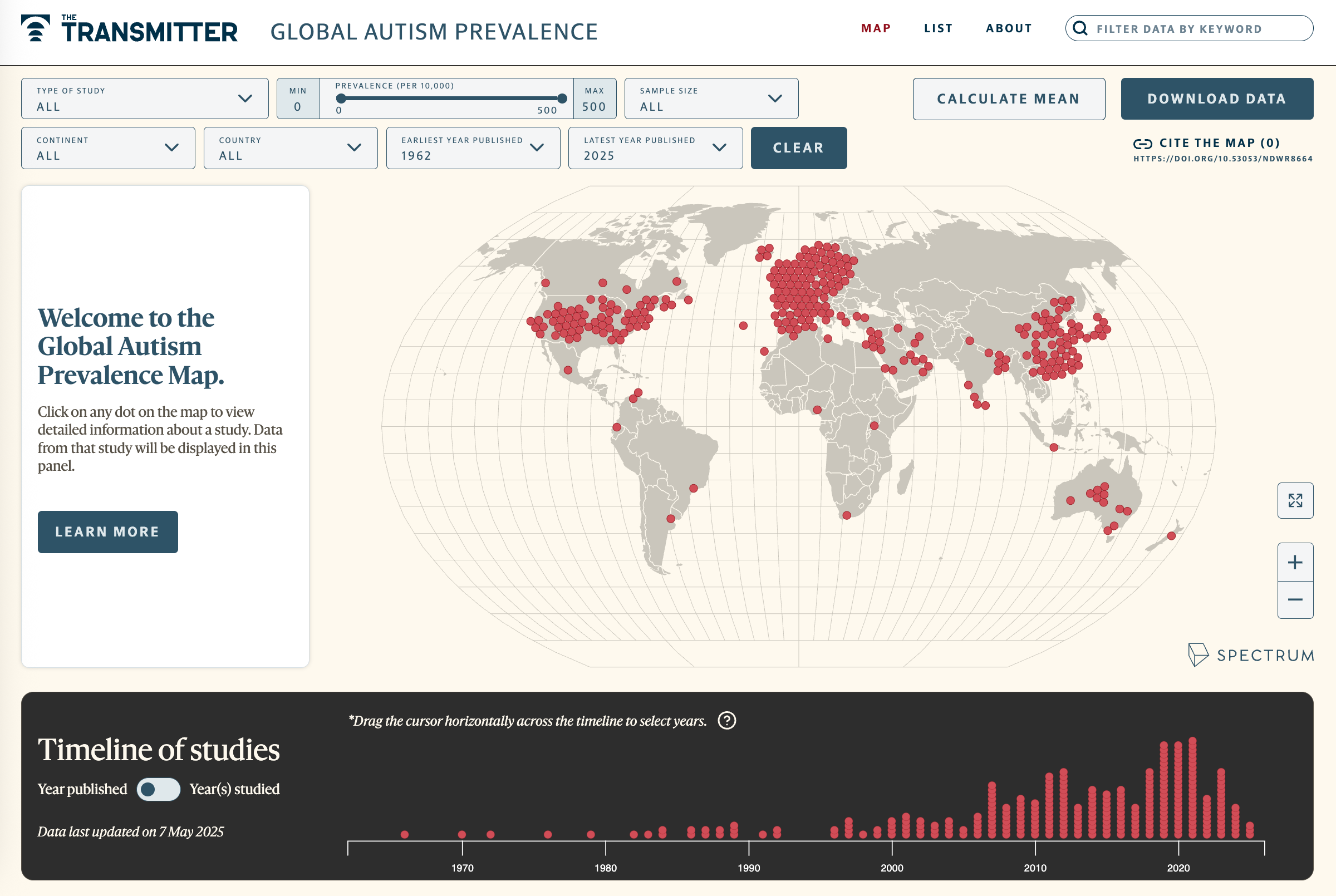

Visit our Global Autism Prevalence Map

Explore more >

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

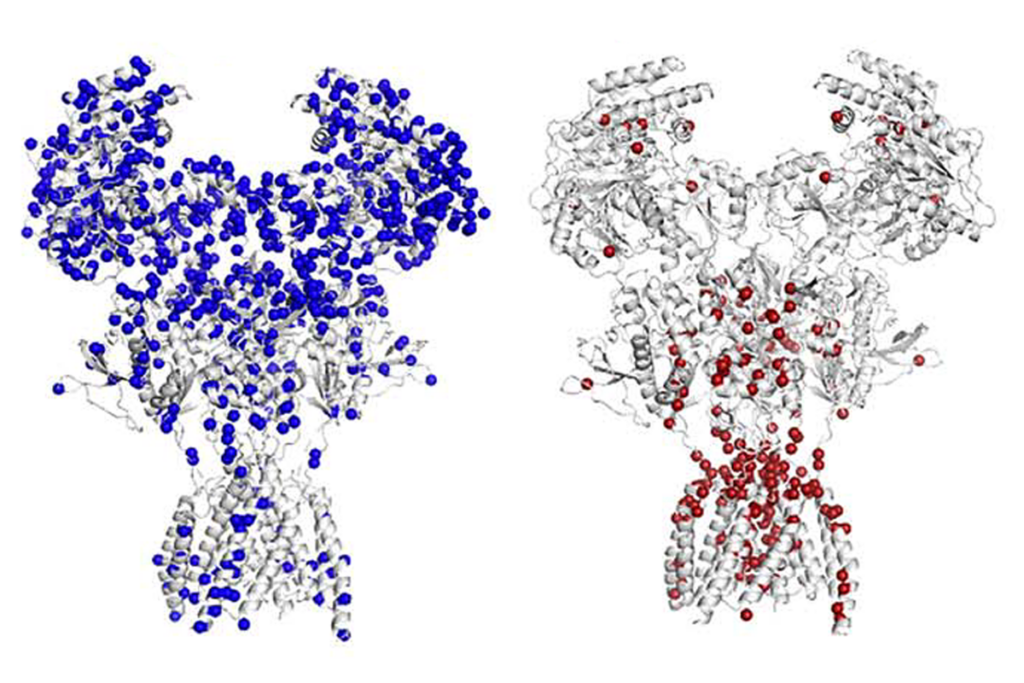

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Explore more from The Transmitter

Autism prevalence increasing in children, adults, according to electronic medical records

Anti-seizure medications in pregnancy; TBR1 gene; microglia