Children from minority ethnic groups and of low socioeconomic status in eastern and southeastern districts of England had the country’s highest rates of new autism diagnoses between 2014 and 2017, according to a study of more than 7 million schoolchildren.

“The take-home message from this research is that whether or not someone receives an autism diagnosis may be influenced by socioeconomic factors, ethnicity and where they live,” says study investigator Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Autism Research Centre at the University of Cambridge. “This study adds to the evidence that autism incidence varies by sex, age, ethnicity and geographic location but does so on a much larger scale than was previously possible.”

About 1.8 percent of children in England had autism in 2017, according to a 2021 study by Baron-Cohen and his colleagues. That work found a particularly high prevalence of autism among Black and multiracial children, and among unclassified ethnic groups.

But prevalence provides only a snapshot of diagnoses in a population. The new study looked at incidence — the rate of new diagnoses per year — among all 7 million-plus children enrolled in government-funded schools across England. They examined links between autism incidence and sociodemographic factors — including gender, ethnicity, first language, economic disadvantage — to help identify inequalities in accessing a diagnosis.

Between 2014 and 2017, 102,338 schoolchildren received a diagnosis of autism in England, researchers found. This corresponds to an overall incidence of 426.9 cases per 100,000 person-years after adjusting for differences in age and sex.

Incidence was highest among Black children and those of unclassified ethnicity, at 599.4 cases per 100,000 person-years and 466.9 cases per 100,000 person-years, respectively.

“Why are we diagnosing more kids with autism in these communities?” asks lead investigator Andres Roman-Urrestarazu, assistant professor of international health at Maastricht University in the Netherlands. “Maybe it’s structurally engrained in the racism of the health system. But if that’s the case, that’s also part of the discussion.”

T

he pattern is not unique to the United Kingdom: Ethnic-minority immigrants in Sweden also have an unusually high autism prevalence, a 2012 study found. So, too, do children born in Los Angeles, California, to Black, Central or South American, Filipino or Vietnamese mothers, compared with those who have U.S.-born white mothers, according to a 2014 Pediatrics paper. Across the United States, however, the historical gaps are closing for Black and Hispanic populations, studies from the past five years suggest.“Why is it that in Europe we find these things, versus in the States? There’s a larger issue here,” Roman-Urrestarazu says.

It’s an imbalance that has surprised American researchers, Roman-Urrestarazu says. England, Sweden and other Scandinavian countries have nationalized health care — unlike the U.S. — through which anyone who needs a medical treatment referral pathway should be able to access care.

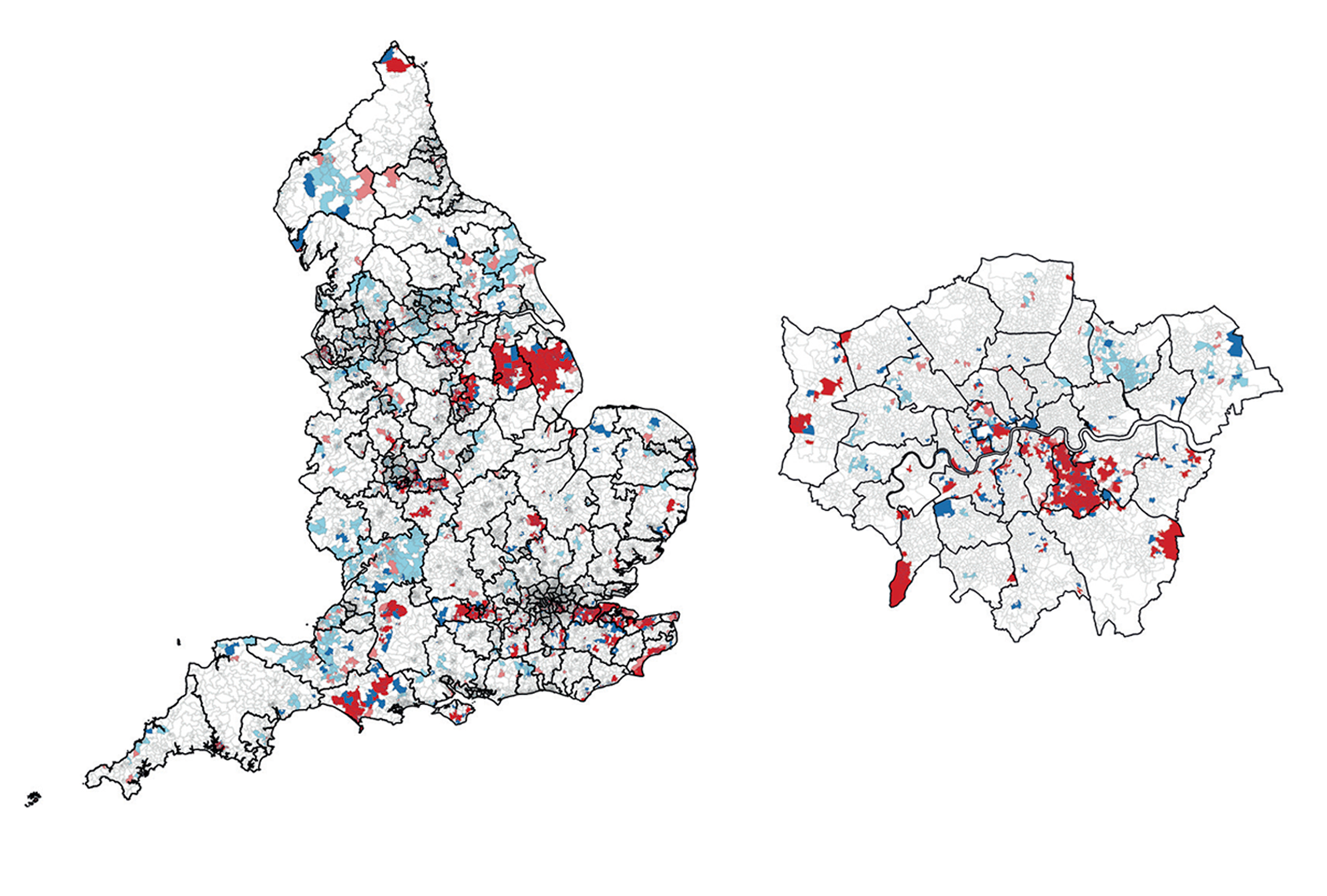

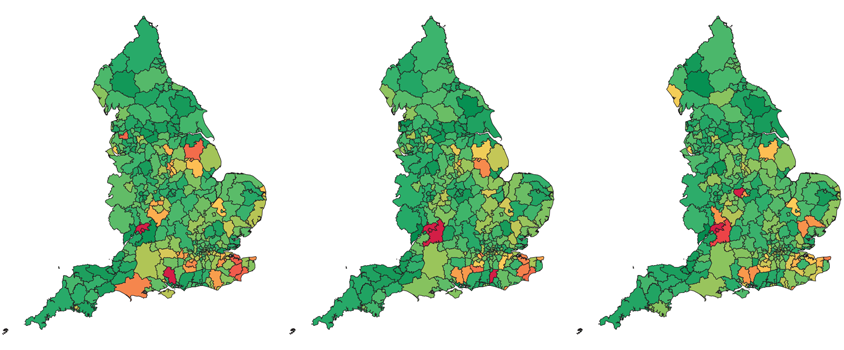

Roman-Urrestarazu’s team conducted a geographic analysis to identify “hot spots” and “cold spots,” where new autism cases are higher or lower than the national average, respectively. Hot spots — found predominantly in South East England as well as the West Midlands and East Midlands regions — often corresponded with research centers, such as the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Biomedical Research Centre; cold spots were more common for girls, meaning there are barriers to diagnosing girls systematically in these areas.

Before this, a large-scale incidence population study that also assesses variability across social and demographic determinants was missing from the field, according to Michael Absoud, a reader in the women and children’s health department at Kings College London, who was not involved in Roman-Urrestarazu’s study but wrote a commentary about it. Both Absoud’s commentary and the new findings appeared in Lancet Child and Adolescent Health in October.

“It confirmed what we’ve seen on the ground but hadn’t evidenced in data,” Absoud says. “That’s helpful for policymakers and for research funders to actually see the data, as opposed to just your inkling.”

R

oman-Urrestarazu’s team analyzed in further detail how gender intersects with incidence. Black and Asian girls had a lower incidence of autism than white girls if none of them had free school meals and they spoke English as their first language — even though Black children had a greater prevalence overall. This disparity points to an inequality in access to diagnosis, the researchers say.Similarly, eligibility for free school meals (an indicator of low socioeconomic status) was associated with an increased likelihood of having autism across all racial and ethnic groups; having a first language other than English tracked with a decreased likelihood. These trends were most apparent in boys.

“This finding might be explained by a paucity of differential diagnosis exploration by clinicians who have difficulties in communicating with these children or their parents or guardians,” Absoud wrote in his commentary.

Because the new study is observational, though, researchers cannot draw conclusions about causation. For example, although family-level deprivation (free school meals) correlates with higher chances of having a child with autism, the researchers cannot tell whether deprivation contributes to autism or whether caring for someone with autism financially strains the family.