Autism families tend to have fewer children than their peers

Parents who have a child with autism often decide not to have any more children, according to a study published last week in JAMA Psychiatry.

Parents who have a child with autism often decide not to have any more children, according to a study published last week in JAMA Psychiatry. These parents are about 33 percent less likely to have more children compared with parents who do not have an affected child, researchers found.

With data from 56,000 California families, the study is among the largest assessments of reproductive behavior in families with a history of autism.

The researchers looked at the families of 19,710 children with autism born between January 1990 and December 2003. They compared these families with those of 36,215 controls matched for sex, birth year, maternal age, ethnicity and county of birth.

By the time a child with autism turns 2, his motor and communication difficulties become noticeable. It’s after this point that the parents typically decide to stop having more children.

Women who change partners after having the child with autism are also about half as likely to have another child as controls are.

The researchers also calculated autism’s recurrence within families. When the researchers did not factor in this so-called ‘stoppage’ effect, siblings of children with autism have a nearly ninefold increase in autism risk compared with control siblings, and maternal half-siblings have a threefold increase. These findings are in line with those from two Scandinavian studies published in the past year.

However, when the researchers took stoppage into account, the siblings are at a tenfold increase in autism risk and the maternal half-siblings have a nearly fivefold increase compared with controls.

This suggests that previous studies underestimated the risk of autism for family members of affected children, the researchers say.

The study did not ask the parents of affected children why they chose to stop having children. The researchers speculate that it may be because the parents were concerned about their ability to care for another child, especially if the new child also turned out to have autism.

Recommended reading

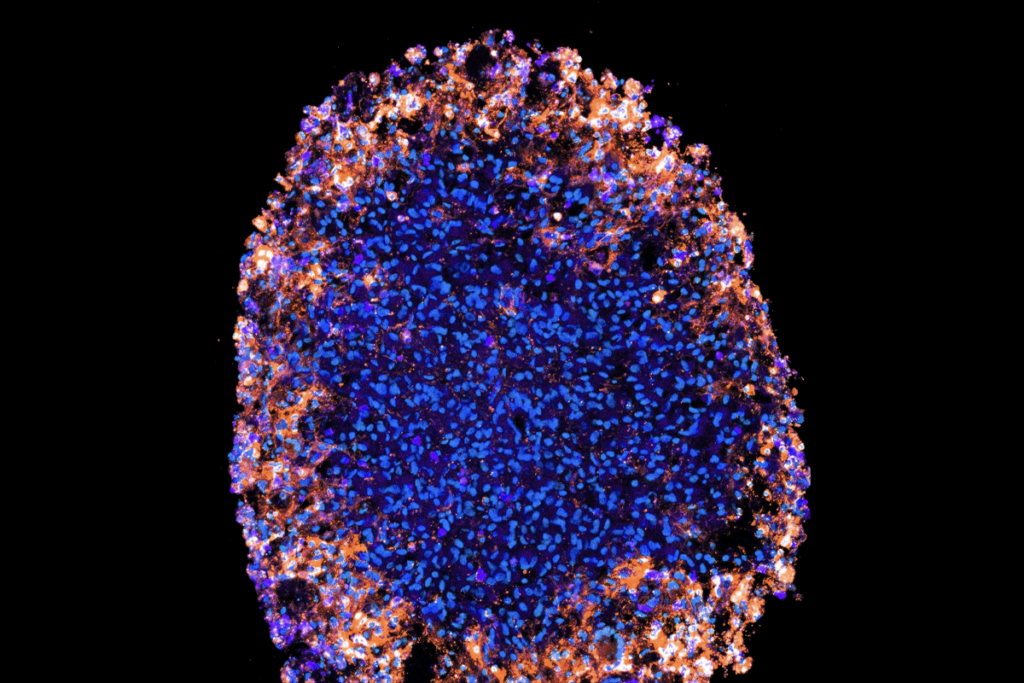

Among brain changes studied in autism, spotlight shifts to subcortex

Home makeover helps rats better express themselves: Q&A with Raven Hickson and Peter Kind

Explore more from The Transmitter

Dispute erupts over universal cortical brain-wave claim

Waves of calcium activity dictate eye structure in flies