Autism brains show connectivity differences that vary by region

The brains of people with autism have unusually strong connections in some regions and weak ones in others.

The brains of people with autism have unusually strong connections in some regions and weak ones in others, according to the largest-yet study to explore these trends1.

For more than a decade, researchers have posited that the brains of autistic people have atypical functional connections — patterns of communication between brain regions. But exactly what those differences are has been unclear: Some studies have reported more connectivity in autistic brains; others saw less. Still others have suggested that the difference is not in the degree of connectivity but in how connections vary over time.

The new study set out to resolve these inconsistencies.

“Our key objective was to find common ground across the existing literature,” says lead investigator Juergen Dukart, group leader in biomarker development at Jülich Research Center in Germany. “There was really no consistency at all in terms of the methodology applied or the patient populations.”

Based on scans from nearly 2,000 people, the researchers found distinct patterns of functional connectivity in the brains of people with autism.

The findings unequivocally indicate that autistic people have biologically relevant differences in their brain connections, says Tal Kenet, instructor in neurology at Harvard Medical School, who was not involved in the study.

“It’s a fantastic paper,” Kenet says. “Across all the different cohorts, they found a significant group difference, with an effect size in the large range for several of them.”

Counting connections:

Dukart’s team analyzed data from functional magnetic resonance imaging scans of the brains of 841 autistic people and 984 controls. The participants came from four large, ongoing studies of autism. The scans were done while the participants rested, gleaning activity in the brain at rest.

The researchers first analyzed data from 394 participants (202 of them with autism) from one of the studies. For each small volume, or ‘voxel,’ on a scan, they counted the number of functional connections between neurons.

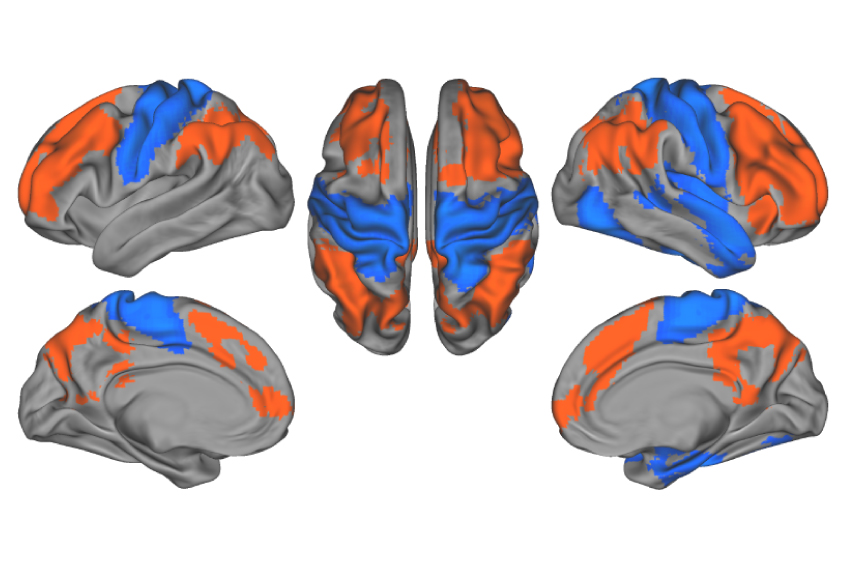

Autistic people have more connections involving two large swaths of the brain’s surface — the frontal and parietal cortex — than controls do, the study found. These regions govern various aspects of complex thought.

By contrast, the sensorimotor and temporal cortex in these people make fewer connections with other parts of the brain than they do in controls. Sensorimotor areas process sensory stimuli and govern movement, and the temporal cortex manages sound and language processing.

The same pattern popped out in scans from two of the other studies. The fourth set of scans showed an increase in connectivity in the frontal and parietal areas but not a decrease in the sensorimotor and temporal regions.

Together the findings indicate that the overall degree of connectivity in the brain is preserved in autism, but the pattern of connectivity is not, Dukart says.

Trait ties:

These connectivity patterns do not depend on age, sex or medication use. In two of the datasets, they track with limited speech and other communication skills, and with difficulties in daily living skills, such as self-care or holding down a job.

However, the researchers found no link between connectivity differences and scores on the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS), the gold-standard method for rating autism traits overall.

These associations between connectivity patterns and autism traits are encouraging because they hint at the clinical relevance of the findings, says Leonard Schilbach, head of the Outpatient Clinic and Day Clinic for Disorders of Social Interaction at the Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry in Munich, Germany, who was not involved in the work. However, the reported associations are weak, he says.

In addition, the connectivity measure the researchers used does not reveal the ‘strength’ of each connection — that is, how much it is used. One way to measure strength is to assess the extent to which pairs of brain areas are simultaneously active. The result may reveal stronger associations with behavioral or clinical aspects of autism, Kenet says.

To improve the data analysis, Dukart’s team aims to use more refined methods to acquire and analyze brain-imaging data and to track how functional connectivity changes over one to two years.

References:

- Holiga Š. et al. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaat9223 (2019) PubMed

Recommended reading

Expediting clinical trials for profound autism: Q&A with Matthew State

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Explore more from The Transmitter

Mitochondrial ‘landscape’ shifts across human brain