Autism brains have too many neurons, study suggests

Children with autism have an abnormally large number of neurons in the prefrontal cortex, a brain region important for abstract thinking, planning and social behaviors, according to a study published yesterday in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Children with autism have an abnormally large number of neurons in the prefrontal cortex (PFC), a brain region important for abstract thinking, planning and social behaviors, according to a study published yesterday in the Journal of the American Medical Association1.

Because of the study’s small sample size, however, and the complexities of analyzing postmortem brains, many researchers caution against interpreting the results as relevant for all children with autism.

In the study, researchers analyzed postmortem brain tissue from two areas of the PFC from seven boys with autism and six controls, ranging in age from 2 to 16 years. In the brains from the children with autism, the dorsolateral PFC, which comprises the outer layers of the region, holds 79 percent more neurons, and the mesial PFC, encompassing deeper tissue, holds 29 percent more neurons compared with controls, the study found.

According to lead investigator Eric Courchesne, the study provides a cellular explanation for imaging studies showing brain overgrowth in children with the disorder.

“Now for first time, in my opinion, there’s a fairly robust and specific pathology that can be used in animal model studies and cellular studies to test speculations about genetic and non-genetic factors that could cause this disorder,” says Courchesne, professor of neurosciences at the University of California, San Diego.

Other experts are skeptical of the results, however, saying they may not represent the wider population of children with autism.

“I would emphasize that this study is very preliminary. Only seven individuals with autism were included and it’s just one region,” says Nicholas Lange, associate professor of psychiatry and biostatistics at Harvard University, who wrote a commentary of the study in the same issue of the journal2.

“My overwhelming feeling is that not too much should be made of this at this point,” says David Amaral, director of research at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute. “It would be premature to draw any conclusions until the study has had an independent replication using a much larger number of brains.”

Precious tissue:

Leo Kanner noted large heads in children with autism in his 1943 description of the disorder. Since then, studies have reported that about one out of five children with autism have macrocephaly, or larger-than-normal heads3.

In 2002, Courchesne’s team used brain imaging to show that 2- to 4-year-old boys with autism have significantly more gray matter — brain tissue that includes cell bodies — in the frontal and temporal cortex than healthy controls do, but that this difference disappears by adolescence4.

At the time, he speculated that the enlargement might be due to a glut of neurons, and began collecting postmortem brain tissue to test his hypothesis.

Postmortem studies are plagued by many methodological challenges, first and foremost that brain tissue from individuals with autism is rare.

Anatomical research on a variety of regions in brains of many ages paints a somewhat confusing picture. In the adult autism brain, the amygdala seems to have fewer neurons5, and Purkinje cells in the cerebellum tend to be smaller6, compared with controls.

One study found that hippocampi in the brains of adults with autism hold more inhibitory cells compared with the brains of controls7.

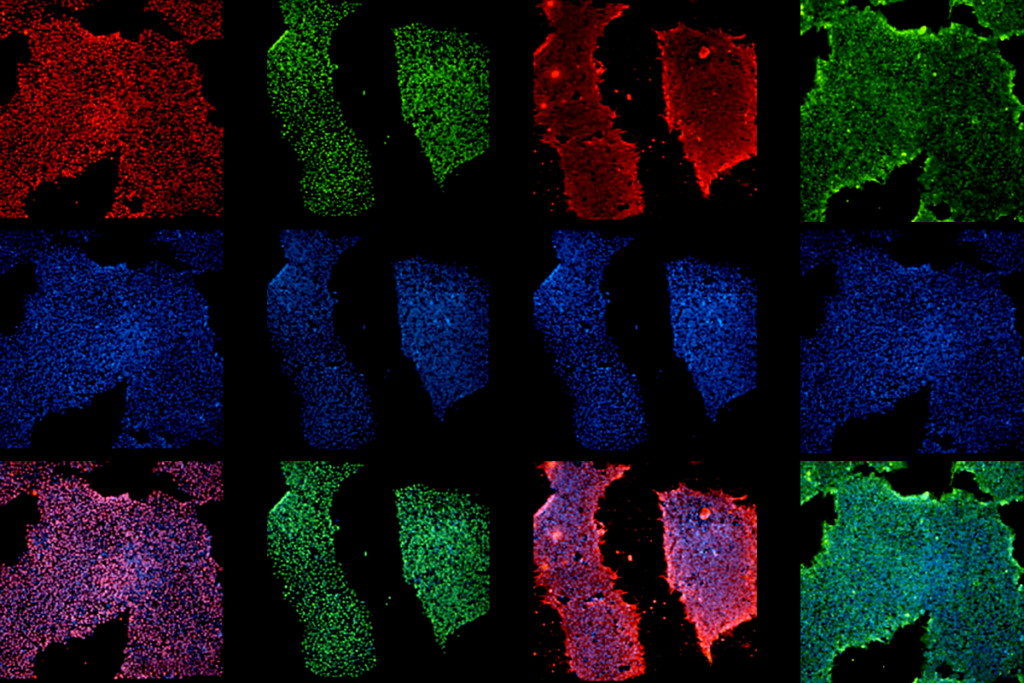

Since 2002, Manuel Casanova and colleagues at the University of Louisville have published several papers — using some of the same brains as in the new study — showing a higher density of neurons in the PFC of autism brains than in that of control brains8. These studies also found that ‘minicolumns’ of connected neurons that stack vertically in the cortex are abnormally narrow and numerous in autism brains.

But one drawback of density measures — which calculate the number of cells per unit volume — is that they can be affected by how the brains are processed after death.

“Tissue goes through dehydration steps and rehydration steps, so you never know how much shrinkage or expansion has taken place,” Courchesne says.

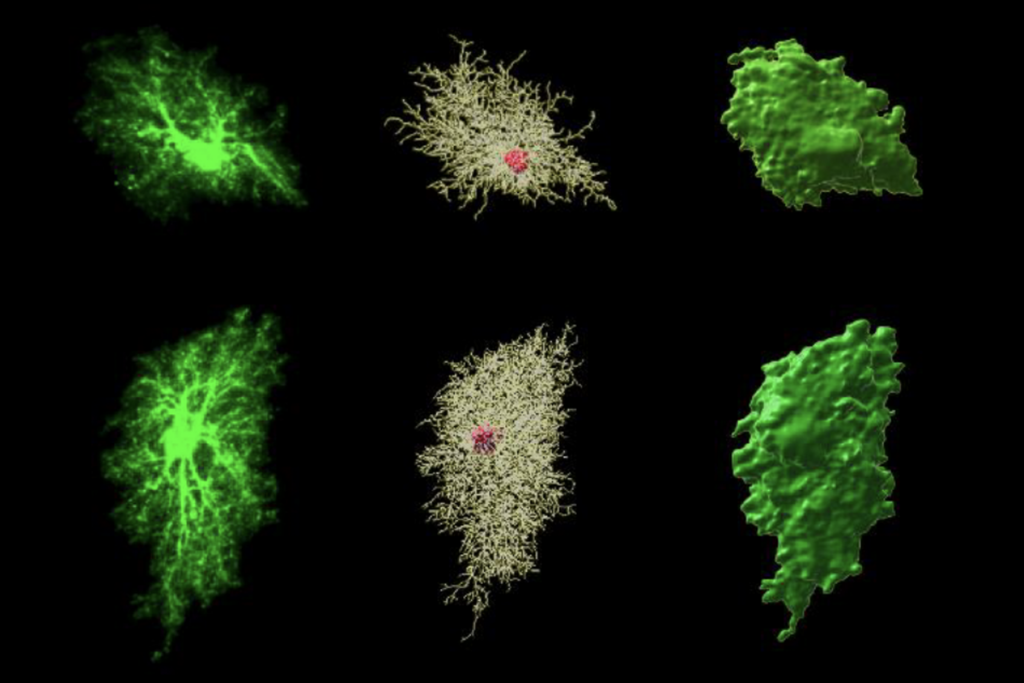

That’s why his team, like most others in the past few years, has measured the total number of neurons using a technique called stereology. This method is difficult, he says, because it requires random sampling from a PFC region in its entirety, and brain banks don’t typically keep tissue samples in such large pieces.

For the new study, Courchesne’s collaborator Peter Mouton, professor of stereology at the University of South Florida College of Medicine, analyzed the unlabeled tissue. “We only do studies in which we’re blind,” Mouton says. “We had one person in Maryland doing some of the counts, another person in Florida doing the others, and then checked them against each other.”

Varying quality:

Other researchers applaud the technique. “Stereology is an unbiased method of quantification,” says Verónica Martinez Cerdeno, assistant professor of pathology at the University of California, Davis.

Still, she and several others say the handful of tissue samples is unlikely to reflect what’s happening in other individuals with autism.

“I know that sample,” says Lange, who is on the advisory board of the Autism Tissue Program, which manages some of the samples in the study. “It’s of varying quality, from poor to acceptable.”

Amaral questions the premise that most children with autism have large brains. In an unpublished imaging study of 180 children, including 114 with autism, aged 2 and 3 years, his team has found that only about ten percent have larger-than-normal brains. What’s more, some work suggests that about 15 percent of children with autism have abnormally small brains3.

“As an anatomist, I would find it very, very, very surprising that those kids who have brains in the same size range as typically developing kids have increased numbers of neurons as portrayed in this paper,” Amaral says.

It will be difficult to understand what’s happening in the brains of the wider autism population until researchers look at many more brain samples.

Several nonprofit organizations and the National Institutes of Health have begun to discuss creating a centrally organized brain bank for autism. The MIND Institute is setting up a pilot site to demonstrate how this might work, Amaral says.

“For ten years, people have been complaining about the lack of brains, but nothing has happened,” Amaral says. “In the next few years there has to be strong advocacy for it, and we’re committed to it.”

* Copyright © 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

References:

1: Courchesne E. et al. JAMA 306, 2001-2010 (2011) Abstract

2: Lainhart J.E. and N. Lange JAMA 306, 2031-2032 (2011) Abstract

3: Fombonne E. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 29, 113-119 (1999) PubMed

4: Carper R.A. et al. Neuroimage 16, 1038-1051 (2002) PubMed

5: Schumann C.M. and D.G. Amaral J. Neurosci. 26, 7674-7679 (2006) PubMed

6: Fatemi S.H. et al. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 22, 171-175 (2002) PubMed

7: Lawrence Y.A. et al. Acta Neurol. Scand. 121, 99-108. (2010) PubMed

8: Casanova M.F. et al. Neurology 58, 428-432 (2002) PubMed

Recommended reading

Explore more from The Transmitter

Bringing African ancestry into cellular neuroscience