Autism and Schizophrenia: A tale of two disorders

For much of the twentieth century, autism was considered childhood schizophrenia.

For much of the twentieth century, autism was considered childhood schizophrenia.

Shared problems with language and social interaction lumped them together. Doctors thought as the children grew older, they simply became more psychotic and delusional.

But, in 1943, Leo Kanner, a psychiatrist at Johns Hopkins University, suggested that children who have an “innate inability” to form relationships with people have a distinct disorder that he dubbed early infantile autism1.

Thus began a passionate psychological debate over the next 30 years: should autism be considered a separate entity, or part of the schizophrenic syndrome complex?

Clinical differences between the two disorders led to diverging research, but new evidence that suggests they are related diseases may spark the debate anew.

On 5 May, Swedish researchers revealed that, based on health records from more than 1,200 families, parents of children diagnosed with autism are twice as likely to have been diagnosed with schizophrenia as controls2. The mothers of those children with autism are also 1.7 times as likely to have been diagnosed with depression or personality disorders.

Using cutting-edge genetic technologies, researchers are also finding the same random genetic variants ― particularly in genes involved in neurodevelopmental pathways ― in both autism and schizophrenia.

“The epidemiology didn’t teach us there could be a common basis to distinguish between disorders,” says Jonathan Sebat, a geneticist at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in New York. “Genetics is teaching us that.”

Diverse genetics:

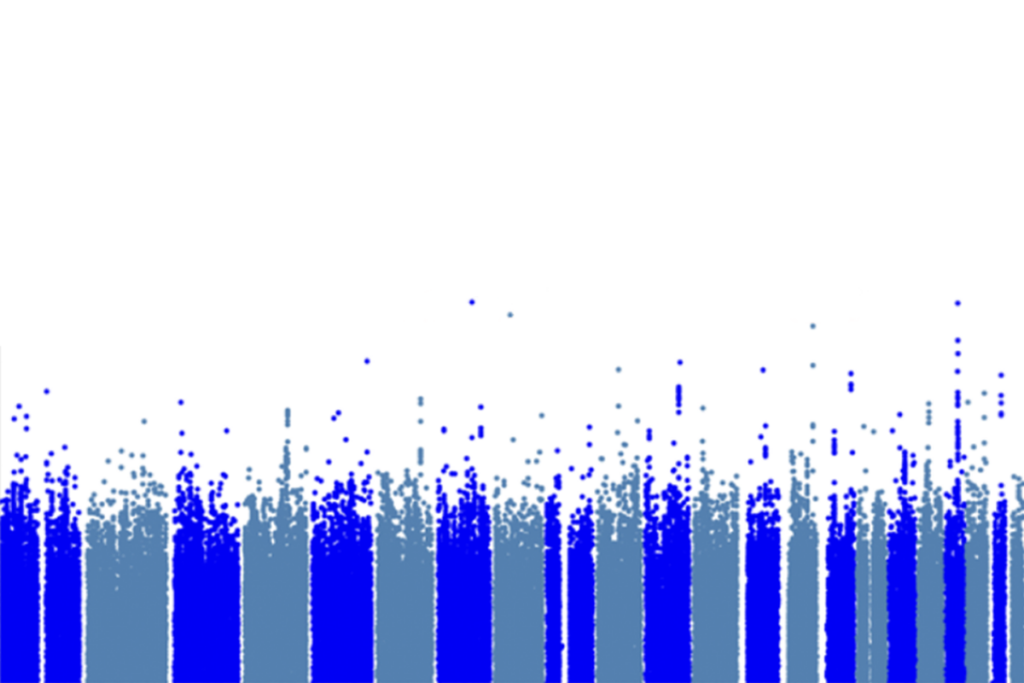

Scientists have long known that individuals with autism and those with schizophrenia both have chromosomal abnormalities. But in the past two years, technology has allowed scientists to confirm that deletions or duplications of chunks of the chromosomes are important in both disorders.

These copy number variations (CNVs) occur de novo, meaning they are spontaneous, random mutations not carried by the parents ― a somewhat shocking revelation for a neurodevelopmental disease with evident genetic origins.

“There is no stronger genetic disease in the psychiatric world than autism,” Sebat says. “But strangely, in families it didn’t seem to segregate in a classic Mendelian way ― where one trait is passed down in a dominant or recessive fashion,” he adds.

Although there are obvious cases of autism inherited from one or both parents, spontaneous or ‘sporadic’ cases, in which children have two unaffected parents, are also common.

Knowing there was more complex genetics at work, Sebat and his colleagues searched for random genetic glitches in children with autism and typically developing controls. What they found suggests that more than 15 percent of autism cases result from CNVs, with possibly hundreds of genes involved3.

The researchers found 17 CNVs, predominantly in cases of sporadic autism. “CNVs do not occur as frequently in families with more than one autistic child,” Sebat says.

Ironically, genetic studies of autism had gone to incredible lengths to recruit multiplex families, rare cases in which more than one child in the family is diagnosed with autism. But that, Sebat says, ignores the role of de novo mutations.

The combined genetic evidence lends support to a hypothesis that suggests that autism is the result of several genetic variations, some of which can occur spontaneously.

“Autism genes are everywhere ― probably because the brain hijacks so much of the genome in the process of wiring itself that there are a number of potential sites that can be disrupted during brain development,” says Sebat.

Many of these CNVs may be one-off mutations, never found to be statistically significant, but are highly penetrant, meaning that nearly everyone with that mutation will develop autism.

What that suggests, however, is that almost every individual with sporadic autism has a different CNV.

“It’s comparable to a car’s engine: a malfunction in any number of the many different wires or moving parts can bring the car to a halt,” says Steve Hamilton, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

Striking similarities:

Following these findings in autism, different groups have discovered genetic overlap between patients with adult-onset psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

For example, Sebat’s team found that CNVs are also unexpectedly frequent in schizophrenia. What’s more, a handful of the 53 CNVs found in people with schizophrenia are also prevalent in individuals with autism4.

Some areas appear to be hot spots for mutations. For example, a duplicated region of chromosome 16 has been found in two people with childhood-onset schizophrenia and in seven people with autism5. A deletion of the same region has also been found in five individuals with autism and in two with bipolar disorder6.

It’s more difficult to predict whether some of the other CNVs are pathogenic. But there is growing evidence that autism, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are likely to involve similar pathways.

In November 2007, a collaboration of European geneticists reported that of 13 CNVs they had found in people with schizophrenia, only two may be pathogenic. One of those, an inherited trait, was found to disrupt the neurexin 1 gene (NRXN1), crucial for the formation of synapses. The NRXN1 gene has also been found to be deleted in some cases of autism7.

Another, in the APBA2 gene ― which codes for a protein linked to Alzheimer’s disease, is a random duplication. But it is intriguing because APBA2 binds to NRXN1 and is known to be important for the normal development and functioning of synapses8.

The alpha-neurexin deletion is rare, but its presence in both disorders is striking, particularly as it was not passed down in the families. “This is not just a benign genetic variant,” says Sebat.

Baseline rate:

Although it is intriguing to ponder the genetic commonalities between autism and schizophrenia, Michael Owen, who heads the psychological medicine division at Cardiff University in the UK, suggests caution when interpreting these early results.

“We don’t yet know just how common these things are in general populations,” he says. Studies so far have used small numbers from the general population to establish a baseline rate of CNVs. Larger numbers of controls are needed for statistical significance, he says. “Until we conduct more studies, I’m concerned that these things turning up in both disorders may be due to chance.”

More work is also needed to determine how mutations in specific genes can be pathogenic in these disorders, adds Hamilton.

But Sebat’s work will help reconcile whether and how structural variants connect schizophrenia to autism, Hamilton says. “What are real boundaries between these disorders? There may not be any,” he says.

To pinpoint common mechanisms between disorders, patients should be grouped on the basis of known genetic variants ― rather than by diagnosis ― and by similarities and differences in brain scans or cognitive function, notes Jack McClellan, medical director of the Child Study and Treatment Center at Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center in Seattle, Washington.

“Using data already collected, we can flip things around and get a better understanding of which factors in neural development go wrong,” McClellan says. “It may be a case where one mutation in a gene leads to autism and a different mutation in the same gene leads to schizophrenia.”

Those differential effects may result from other genetic influences, environmental factors, or just chance9. Grouping patients by genetic variants may also help understand the spectrum of phenotypes associated with the disorders.

“If something modulates the severity of neurodevelopmental disorders,” Sebat notes, “it might be something to exploit for treatment or therapy.”

References:

-

Kanner L. Behav. Sci. 10, 412-420 (1965) PubMed

-

Daniels J.L et al. Pediatrics 121, 31357-31362 (2008) PubMed

-

Sebat J. et al. Science 316, 445-449 (2007) PubMed

-

Walsh T. et al. Science 320, 539-543 (2008) PubMed

-

Kumar R.A. et al. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 628-638 (2007) PubMed

-

Weiss L.A. et al. New Engl. J. Med. 358, 667-675 (2008) PubMed

-

Kim H.G. et al. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82, 199-207 (2008) PubMed

-

Kirov G. et al. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 485-465 (2008) PubMed

-

Cantor R.M. and D.H. Geschwind Neuron 58, 165-167 (2008) PubMed

Explore more from The Transmitter