Autism abounds in ‘deprived’ neighborhoods

Children living in low-income neighborhoods with high unemployment rates are more likely to be diagnosed with autism than are children who live in high-income communities, reports a large Swedish study published 26 February in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

Living in a neighborhood with high unemployment rates and low levels of income and education is associated with several unhealthy behaviors, including smoking, and with ill health in general.

Children living in such neighborhoods also have an elevated risk of autism compared with those who live in high-income neighborhoods, reports a large Swedish study published 26 February in the Journal of Psychiatric Research.

The new study is the largest to date to examine the relationship between socioeconomic factors and autism diagnoses. Its findings are in line with some studies — but others have famously found the opposite trend to be true. For example, a 2011 study in New Jersey showed that autism diagnoses are more prevalent in high-income areas and less so in less affluent ones, perhaps because the former have better access to healthcare.

The new study looked at 643,456 children, aged 2 to 11 years, living in Sweden from 2000 to 2010. During that time, 1,699 of the children received a diagnosis of childhood autism, a subtype of the disorder in which symptoms appear before 3 years of age.

Roughly 1,000 people live in each neighborhood the researchers assessed. To determine each area’s socioeconomic status, the researchers evaluated the residents’ average education and income levels, their unemployment rates and whether they received social welfare assistance.

Based on the results, they categorized each neighborhood as having low, moderate or high levels of deprivation.

Overall, 18 percent of the children in the study live in deprived neighborhoods. Another 62 percent live in moderate neighborhoods and the remaining 20 percent in affluent neighborhoods.

The study found that new cases of childhood autism were highest in the deprived neighborhoods: 3.6 per 1,000 people over the ten-year period compared with 2.5 in the midrange neighborhoods and 2.2 in the most well off.

Children living in deprived neighborhoods are 59 percent more likely to be diagnosed with autism than are children in upscale neighborhoods. Once the researchers controlled for individual and family characteristics such as age, sex, income and education, the increased risk fell to 28 percent.

In the U.S., wealthy families usually have better access to specialists, such as psychiatrists who diagnose autism, than families in low-income neighborhoods. In contrast, Sweden’s universal healthcare system provides medical services to people of all incomes.

Given this, the study’s results suggest that low socioeconomic status is associated with an increased risk of autism, the researchers say.

Children who have older parents, siblings with autism or single mothers are also at an increased risk of the disorder, the study found.

Children who live in urban areas are also more likely to be diagnosed with childhood autism, possibly because cities have more specialized medical resources, the researchers say.

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

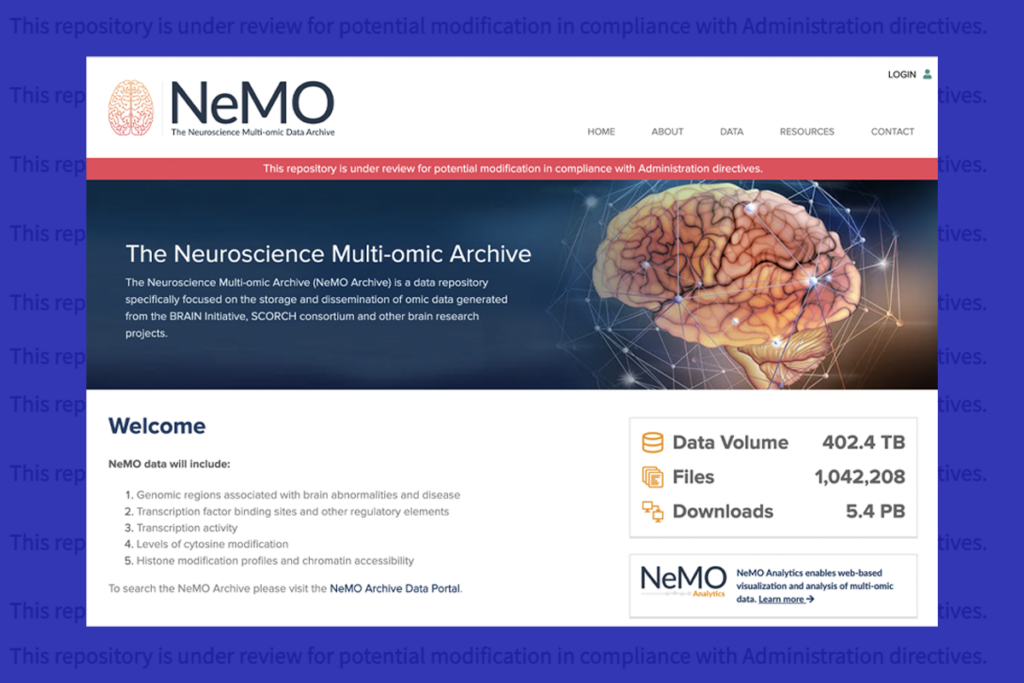

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors