Attention deficit disorder, autism share cognitive problems

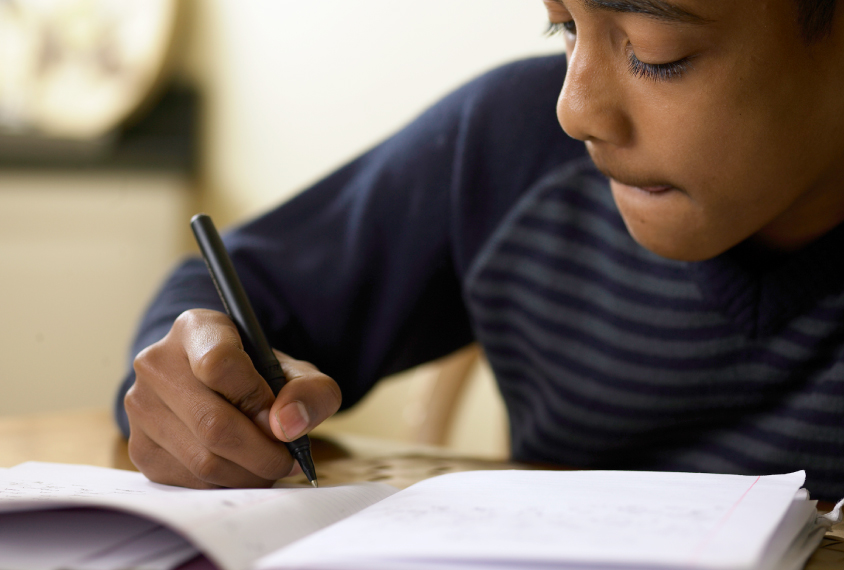

Children with autism may have many of the cognitive difficulties seen in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Children with autism have many of the cognitive difficulties seen in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), a new study suggests1.

In particular, these children struggle with executive function — a set of mental skills that underlie planning, self-control, short-term memory and decision-making.

The findings suggest that cognitive problems are an inherent part of autism and occur independently of other features of ADHD. They may reflect the genetic overlap between the two conditions.

“Because they occur in both disorders independently, they may be associated with some kind of shared liability or shared genetic risk,” says lead investigator Sarah Karalunas, assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

With nearly 1,000 participants, the study is among the largest and most comprehensive to compare children with autism, ADHD or features of both.

“The field has been looking for studies like this,” says Benjamin Yerys, a child psychologist at the Center for Autism Research at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study.

Sacrificing speed:

Karalunas and her colleagues evaluated cognitive abilities in 97 children with autism, 509 children with ADHD and 301 controls. All of the children were 7 to 15 years old and had an intelligence quotient of at least 70.

The children completed six standardized tests of cognitive function. And parents filled out questionnaires about their child’s ADHD or autism features.

Children with autism or ADHD score worse than controls on tests of short-term memory, mental-processing speed and impulse control. The results did not change when the researchers controlled for variability in ADHD features, such as inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, within the autism group. They also did not change after controlling for variability in autism traits, such as social communication difficulties and restricted interests, in the ADHD group. The work appeared 15 February in the Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology.

The researchers also found that children with autism show at least one unique cognitive trait. On a test of reaction time, they emphasize accuracy, whereas children with ADHD balance accuracy with speed, just as controls do.

The test requires pressing computer keys in response to letters lighting up on a screen. The children received instructions to perform the task as quickly and accurately as possible. The ones with autism sacrificed speed in favor of accuracy, whereas children with ADHD and controls struck a balance between the two goals.

“I think [the researchers] have found something that is very, very interesting,” says Uta Frith, emeritus professor of cognitive development at University College London, who was not involved in the work. “The autism group needs more evidence before they actually make their decision, so they are more cautious.”

The reason for this discrepancy between the groups remains unclear, however.

“Anecdotally, I would say that sort of fits with kids with autism, who may be more detail oriented or focused, and may have some perfectionism,” Yerys says.

But it may boil down to a communication problem rather than a cognitive one, Frith says: The children with autism may simply have trouble understanding the instruction to be fast as well as accurate.

Varying the instructions might reveal whether communication is the issue, Karalunas says. If children with autism can adjust their behavior to focus solely on accuracy or on speed, communication is unlikely to be the sticking point. She hopes to test this idea but does not yet have funding to do so.

References:

- Karalunas S.L. et al. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. Epub ahead of print (2018) PubMed

Recommended reading

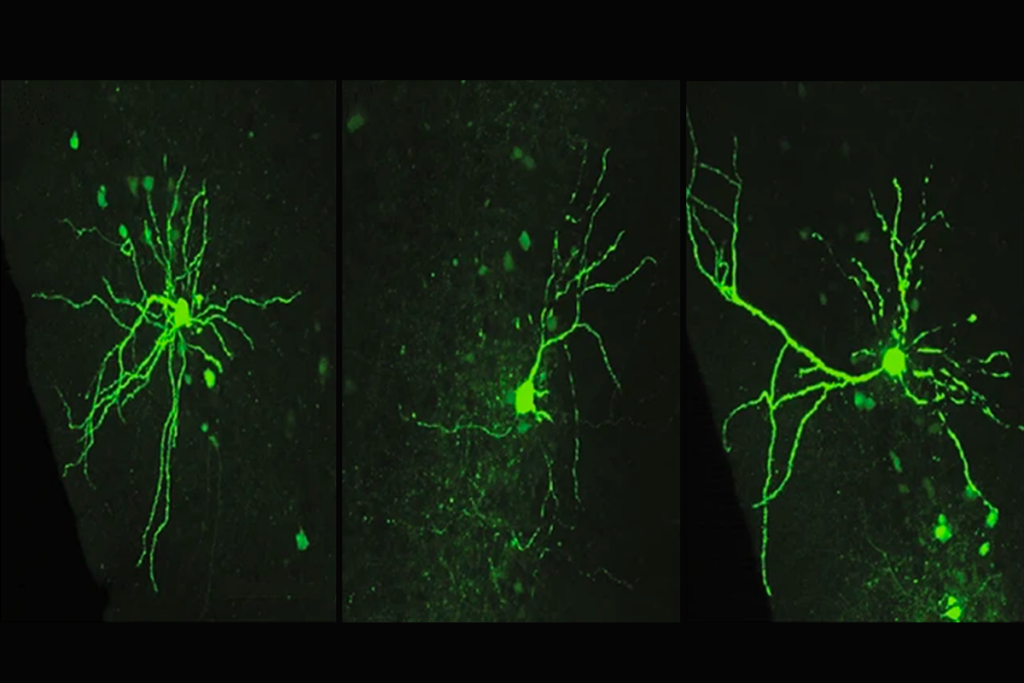

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

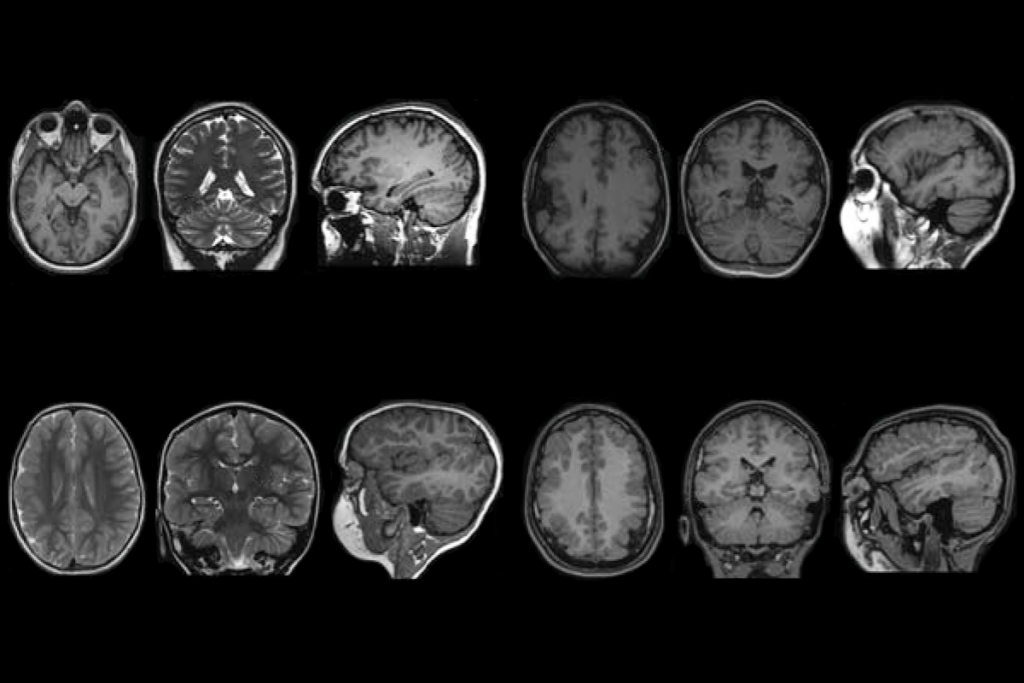

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence