Attention deficit diagnoses nearly double in two decades

The number of children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) has reached more than 10 percent, a significant increase during the past 20 years, according to a new study.

The number of children diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the United States has reached more than 10 percent, a significant increase during the past 20 years, according to a study released 31 August.

The rise is most pronounced in minority groups, suggesting that better access to health insurance and mental health treatment through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) might have played some role in the increase. The rate of diagnosis during that time period doubled in girls, although it is still much lower than in boys.

But the researchers say they found no evidence confirming frequent complaints that the condition is overdiagnosed or misdiagnosed.

The U.S. has significantly more instances of ADHD than other developed countries, which researchers say has led some to think Americans are overdiagnosing children. Wei Bao, who led the study, says that a review of studies around the world doesn’t support that.

”I don’t think overdiagnosis is the main issue,” he says.

Nonetheless, those doubts persist. Stephen Hinshaw, who co-authored a 2014 book called “The ADHD Explosion: Myths, Medication, Money, and Today’s Push for Performance,” compared ADHD with depression. He says that neither condition has unequivocal biological markers, so it makes it hard to determine if an individual truly has the condition without lengthy psychological evaluations. Symptoms of ADHD can include inattention, fidgety behavior and impulsivity.

“It’s probably not a true epidemic of ADHD,” says Hinshaw, professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley and professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “It might be an epidemic of diagnosing it.”

Improved access:

In interpreting their results, however, the investigators tied the higher numbers to better understanding of the condition by doctors and the public, new standards for diagnosis and an increase in access to health insurance through the ACA.

Because of the ACA, “some low-income families have improved access to services and referrals,” says Bao, assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Iowa.

The study, published in JAMA Pediatrics, used data from the National Health Interview Survey, an annual federal survey of about 35,000 households. It found a steady increase in diagnoses among children, from about 6 percent of children between 1997 and 1998 to more than 10 percent between 2015 and 2016.

Advances in medical technology also may have contributed to the increase, according to the study. Two decades ago, preterm or low-weight babies had a harder time surviving. Those factors increase the risk of being diagnosed with ADHD.

The study also suggests that fewer stigmas about mental health care in minority communities may also lead to more people receiving an ADHD diagnosis.

In the late 1990s, 7.2 percent of non-Hispanic white children, 4.7 percent of non-Hispanic black children and 3.6 of Hispanic children were diagnosed with ADHD, according to the study.

By 2016, it was 12 percent of white children, 12.8 percent of black children and 6.1 percent of Hispanic children.

Over the past several decades, Hinshaw says, there’s been an expanded view of who can develop ADHD. It’s no longer viewed as a condition that affects only white middle-class boys, just as eating disorders are no longer seen as afflicting only white middle-class girls.

Still, he cautions against overdiagnosing ADHD in communities where behavioral issues could be the result of social or environmental factors, such as overcrowded classrooms.

Silent subtype:

The study found that rates of ADHD among girls rose from 3 to more than 6 percent over the study period. This is partly a result of a change in how the condition is classified, according to the study. For years, ADHD pertained to children who were hyperactive. But in recent years, the American Psychiatric Association added to its guide of mental health conditions that diagnosis should also include some children who are inattentive, Bao says. That raised the number of girls, he says, because it seems they are more likely to be in that second subtype.

“If we compare these two, you can easily imagine people will easily recognize hyperactivity,” he says.

That rings true for Ruth Hay, a 25-year-old student and cook from New York who now lives in Jerusalem. She was diagnosed with what was then called ADD the summer between second and third grade.

Hay says her hyperactive tendencies aren’t as “loud” as some people’s. She’s less likely to bounce around a room than she is to bounce in her chair, she says.

Yet despite her early diagnosis, Hay says, no one ever told her about other symptoms. For example, she says, she suffers from executive dysfunction, which leaves her feeling unable to accomplish tasks, no matter how much she wants to or tries.

“I grew up being called lazy in periods of time when I wasn’t,” Hay says. “If you look at a list of all the various ADHD symptoms, I have all of them to one degree or another, but the only ones ever discussed with me was you might be less focused and more fidgety.”

“I don’t know how my brain would be if I didn’t have it,” she adds. “I don’t know if I’d still be me, but all it has been for me is a disability.”

This story originally appeared on Kaiser Health News. It has been slightly modified to reflect Spectrum’s style.

Recommended reading

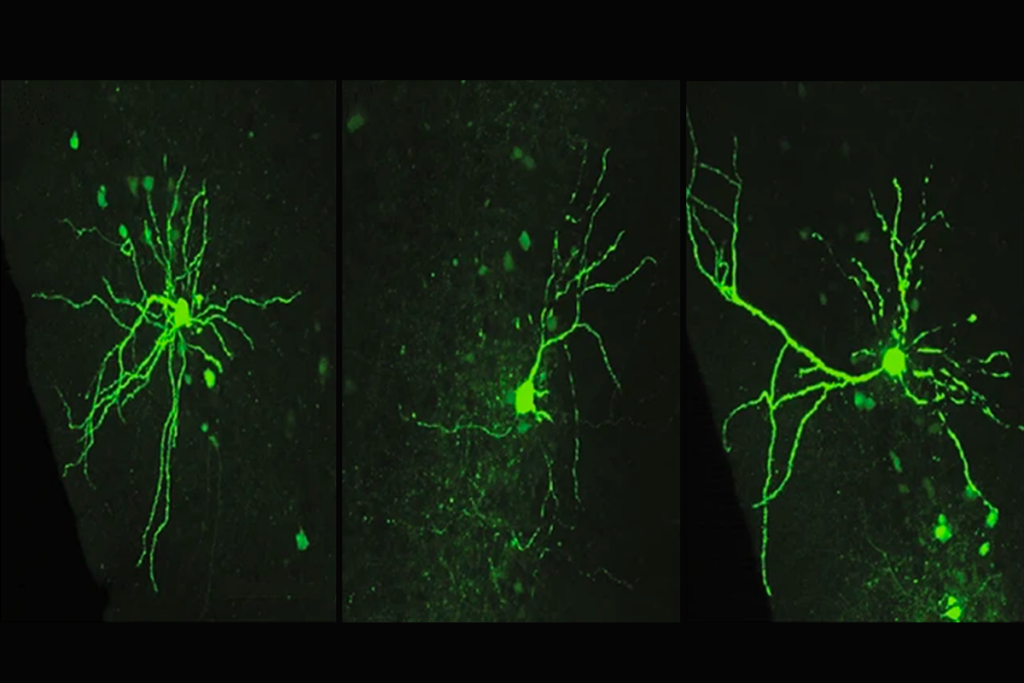

Assembloids illuminate circuit-level changes linked to autism, neurodevelopment

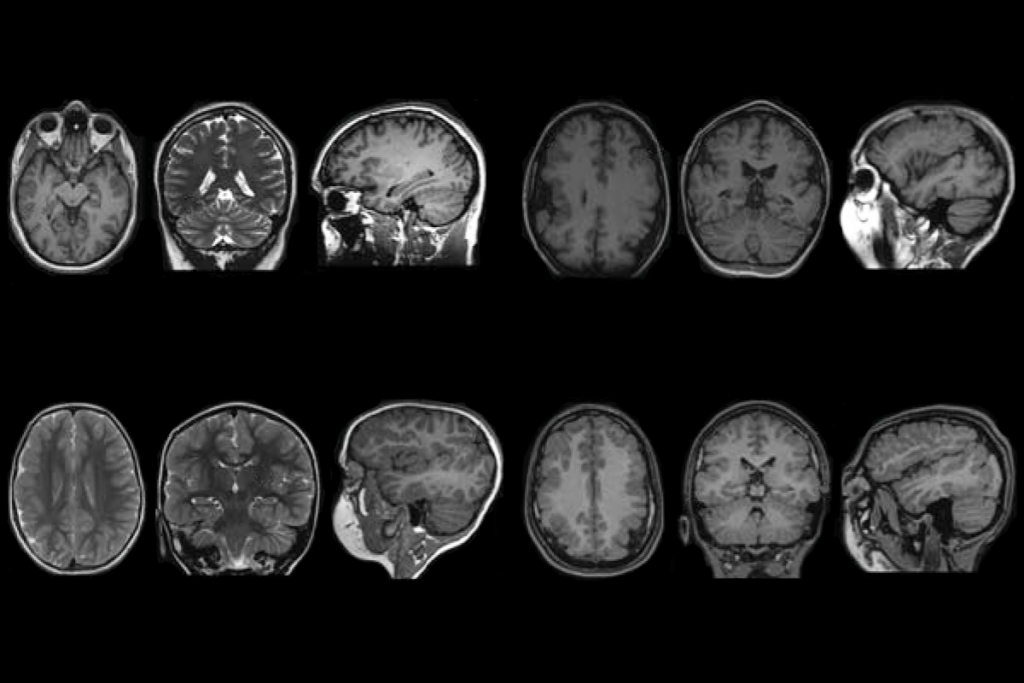

Impaired molecular ‘chaperone’ accompanies multiple brain changes, conditions

Explore more from The Transmitter

The non-model organism “renaissance” has arrived

Rajesh Rao reflects on predictive brains, neural interfaces and the future of human intelligence