Atlas maps flow of neurons in the mouse brain

The Allen Institute for Brain Science is mapping the complex projections of neurons throughout the mouse brain. They presented results from the first 1,400 brains on Tuesday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

The Allen Institute for Brain Science is mapping the complex projections of neurons throughout the mouse brain. They presented results from the first 1,400 brains on Tuesday at the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego.

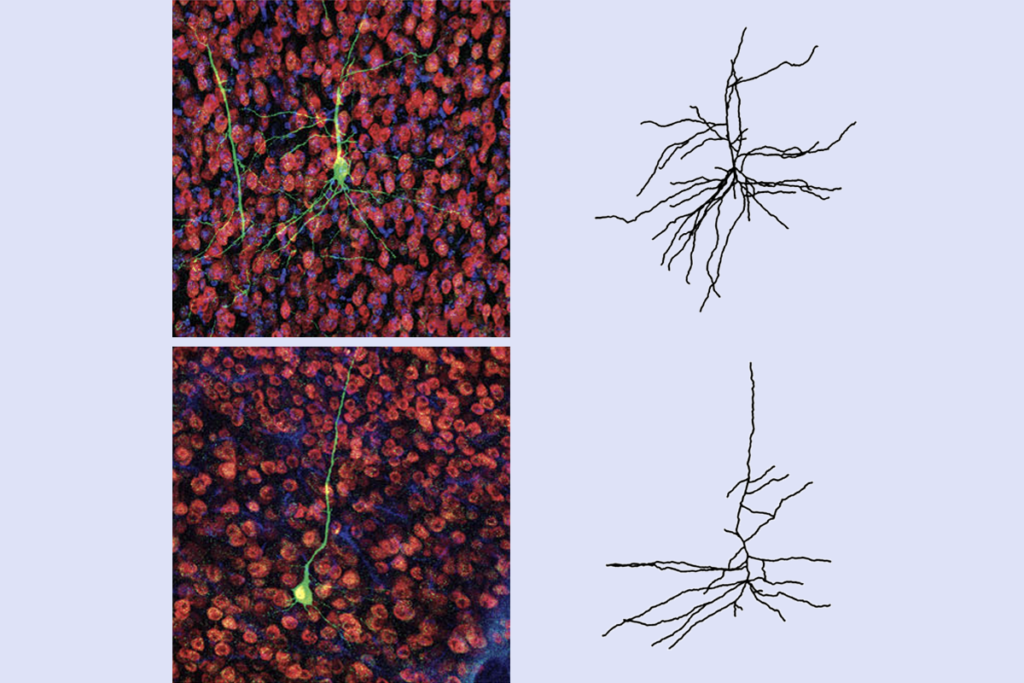

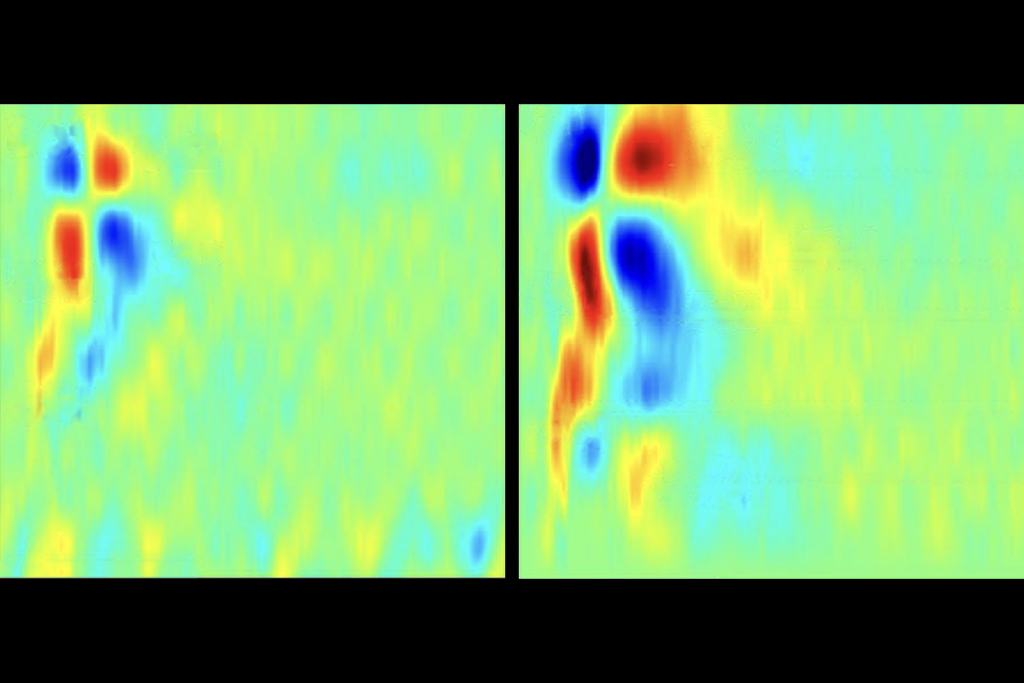

This Mouse Connectivity Atlas shows the spectacularly complex flow of neurons as their projections fan out from 300 regions in the brain.

“I’m always struck by the beauty of this dataset,” says Terri Gilbert, applications scientist at the Allen Institute. “This really does tell you that there’s a cell here and it lays cabling to another region of the brain. And you can actually see it in three dimensions.”

Images of neuronal circuits that span the brain may help researchers understand long-range connections that are thought to be disrupted in autism.

To map neurons, the researchers injected mice in the cortex and the region just beneath it with a rabies virus that encodes a fluorescent protein. They did this in about 200 mouse strains engineered to restrict fluorescence to a certain cell type or brain region. This approach makes the analysis more manageable by limiting the number of neurons that light up in each experiment.

A fully automated system then sliced each brain into 100-micrometer sections, photographed each one and reconstructed the brain from the images. It took the system more than 18 hours to ‘build’ an individual brain from a terabyte of data.

The atlas merges about 1,400 of these experiments together into a single three-dimensional brain, and will continue to add more until March 2014.

Anyone can navigate this atlas — by searching for neurons that project from or through a certain brain region, for example. “We put the data online as we get it, so I see it at the same time as everybody else now,” says Julie Harris, assistant investigator at the Allen Institute who presented the findings.

The next step is to see how the neurons connect at their junctions, or synapses, across the brain. The Allen Institute is pursuing a number of ways to do this, says Gilbert.

Information from the mouse connectivity atlas can be combined with other resources, such as catalogs of gene expression patterns across brain regions. Harris and her colleagues plan to see whether there are differences in the way cells from different regions, such as the motor and visual cortex, project across the brain.

The atlas is already proving useful to researchers. For example, a team of scientists recording electrical activity from distant parts of the brain used the resource to confirm that these regions are, in fact, connected, says Gilbert.

“With all these experiments together, you can do a lot of things that you couldn’t do before,” she says.

For more reports from the 2013 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting, please click here.

Recommended reading

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more