Ask me first: What self-assessments can tell us about autism

With a growing acknowledgement of self-awareness in people with autism, self-report questionnaires are gaining popularity in research and clinical practice.

J

ust moments earlier, the teenager had been laughing so hard he was in tears. He had spent the day doing improv and other drama-based activities — part of a six-week summer camp in Boston designed to help children with autism build social skills. But when his mother showed up and asked about his day, the boy clammed up.“Do you mean you just sat in a corner and stared at the wall all day?” psychologist Matthew Lerner asked him. It was the summer of 2006 and Lerner had launched the program with a colleague two years earlier. He had witnessed the boy’s giggle fit and hoped to prompt more of a response. “Yes,” the boy replied.

As Lerner soon realized, this teen wasn’t the only camper with autism to react that way at pick-up time. “There were a couple of kids who I remember very vividly,” he says. After a day of smiling and playing with peers, they would respond with silence to their parents’ queries. Lerner saw these teenagers having a good time, but they seemed either to not know it themselves or to be reluctant or unsure how to share that experience with their families.

The disconnect startled Lerner. He continued eavesdropping on end-of-day dialogues between campers and parents and noticed that over the course of the summer, many of those conversations changed in tenor: As the young people with autism gained confidence through their interactions, they began to open up and talk more about their feelings and favorite games. The shift wasn’t just a matter of the campers learning to articulate those experiences, he says. “It was whether they seemed to notice or internalize them at all.”

It was a transformation that helped inspire Lerner’s work today — studying how people describe themselves and why those accounts sometimes differ from other people’s perceptions. He is one of several researchers uncovering ways to use and interpret self-report questionnaires that let people describe and quantify their own traits.

For a long time, such tools were rare in the autism world. Scientists presumed that individuals with severe impairments couldn’t answer questions about themselves, and that most people with autism have poor self-insight to begin with. Now, however, they are rethinking those assumptions. “I think the idea that we can interpret someone’s behavior without asking them [questions] is just not fair,” says Vanessa Bal, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco.

As scientists turn more to self-reports, they are discovering these measures can be difficult to interpret. At the same time, they are finding that no assessment from a single vantage — that of a person with autism, her parents, caregivers, clinicians or teachers — can provide all the answers. “A child with autism may act very differently at home than at school,” says Stephen Kanne, executive director of the Thompson Center for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders at the University of Missouri. That means the child’s parents and teachers may perceive her differently, and how she perceives her own experiences may also be different. By recognizing self-report as a valid viewpoint, researchers and clinicians are gaining insight into how people experience autism, rather than relying only on others’ accounts and observations.

”“The notion that people with autism are just wrong about themselves all the time struck me as implausible.” Matthew Lerner

Know thyself:

S

elf-insight is a nettlesome concept. Most people think they know themselves the best, despite the fact that psychology has repeatedly demonstrated the limits of human intuition. Some individuals on the spectrum expect other people to know them better than they know themselves — and that is not always the case, either.Early observers viewed children with autism — a word derived from ‘autos,’ the Greek word for self — as wrapped up in their own private world. But by the 1980s and 1990s, opinions had swung in a different direction. Some experts argued that autism involves poor introspection, not self-absorption. They noted that people on the spectrum have higher rates of alexithymia, or difficulty recognizing their own feelings, and a limited ability to imagine the minds of others. They guessed this might also extend to having limited self-insight.

Over the past decade, many studies have suggested that the truth falls somewhere in between self-absorption and zero introspection. Autism does not always preclude awareness of one’s own or another’s feelings, and if people with autism lack self-insight, those shortcomings may manifest only in their interactions with others. “It may really be something unique to the perception of social ability,” says Lerner, now assistant professor of psychology, psychiatry and pediatrics at Stony Brook University in New York.

Self-report questionnaires support this picture. One 2014 analysis compared how young people with and without autism evaluate their own personality traits. The researchers reviewed 100 self-reports — half from teens or children with autism and half from those without — plus parent reports for each child. For the most part, the descriptions from parents and children matched well, indicating similar levels of self-awareness. But the young people with autism actually had slightly greater awareness of their own neuroticism, or emotionality, than the typical children. And they agreed less often with their parents on their level of ‘extraversion,’ a measure that calls for insight into social performance and how other people see you.

People with autism don’t always lack self-insight, even in social settings. A study last year found that, like typical people, those on the spectrum answer questions about themselves differently depending on context. For example, they reported having more features of autism when they thought about their own behavior compared with that of typical individuals, and fewer autism features compared with others on the spectrum. That sensitivity, the researchers argue, is in itself a sign of strong self-awareness.

With the growing realization of this self-awareness among people with autism, self-report questionnaires are becoming more in vogue in research and clinical practice. Some assessments ask about specific autism traits, whereas others evaluate mood and quality of life. A few, such as the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) and the Ritvo Autism Asperger Diagnostic Scale-Revised, aim to quantify many autism features at once. Their breadth has made them tempting as a diagnostic shortcut — but it’s not so simple.

The AQ debuted in 2001 as the first self-report tool for assessing autism traits in adults of average intelligence. The 50-question test was not intended to be a diagnostic measure. Even so, its publication made headlines in the popular press, and soon many people were using it to assess themselves. Clinicians, too, had hoped it might help them diagnose people on the spectrum faster than with traditional tests, but a string of studies soon dashed that idea. “It’s very seductive,” says psychiatrist Bram Sizoo of the Dimence Institute of Mental Health in the Netherlands, “but actually, it’s inappropriate.”

Both tests are available online, making them relatively easy to game. People can prep for the tests before seeing a clinician who uses them, particularly if they want — or don’t want — a diagnosis. Also, the tools are not particularly sensitive. In 2015, Sizoo and his colleagues evaluated how well the tests predict whether someone would receive an autism diagnosis from an experienced clinician. In a sample of 210 people and 63 controls, those who scored high were more likely to receive an autism diagnosis, but the tests also missed a substantial proportion of the people who should have been flagged.

A year later, a British study came to a similar conclusion and added a new wrinkle: Not only do many people with autism score below the AQ’s cutoff, but those with anxiety tend to score high, regardless of whether they have autism. An analysis in 2013 found that depression and anxiety can misleadingly inflate scores on the AQ and on another self-assessment tool, the Social Responsiveness Scale.

These findings are not entirely surprising, because the tools are being used in populations they were not designed for. “You’re seeing the evolution of the field as opposed to some type of very considered approach to the development of these tools,” says Kanne, who worked on the 2013 study. “The problem is there’s nothing else out there.”

In 2012, Kanne created a self-assessment called the Subthreshold Autism Trait Questionnaire, meant to measure autism features in the general population. Like many other self-report questionnaires, though, it’s often applied more broadly. Many tools used for adults are adapted from questionnaires designed for parents or clinicians to evaluate children. Until they are validated for those different populations, experts say, they should be coupled with other assessments.

“Use the screens, but don’t rely on them,” says Tony Charman, chair of clinical child psychology at King’s College London. A clinician or researcher still has to use good judgment to, as Charman puts it, “triangulate” across as many sources of information as possible. Says Sizoo: “The wrong conclusion would be there’s no use for these tools in clinical practice, let’s do away with them. I think that would be a shame.”

Mind the gap:

T

here is less doubt about the value of using self-report to understand how people with autism experience the condition. When Lerner was in graduate school, he became fascinated by ‘informant-discrepancy research’ — the study of how to interpret different perspectives on the same person or experience. His interest brought him to work alongside a pioneer in this field, psychologist Andres De Los Reyes at the University of Maryland at College Park. In 2005, De Los Reyes proposed that conflicting reports between people can expose their beliefs, biases and traits.“His model really rocked my world,” Lerner says. It contrasted starkly with older views Lerner had encountered that suggested comparing assessments would reveal nothing more than who’s right and who’s wrong.

Since then, Lerner has examined a number of common discrepancies in autism reports from different vantages. Last year, for instance, he found that the more parents and teachers agree about a child’s autism traits, the more likely it is that a child takes medication, receives services or meets standard criteria for a diagnosis. Looking at either the parent or teacher’s report on a child does not yield as accurate a picture of her impairments as the combination does. “Self-report in isolation is not enough, but neither is parent report in isolation and neither is teacher report in isolation,” says Lerner. “Trying to look at the distance between these things gives us some truly meaningful — clinically meaningful — information that we miss on its own.”

In 2016, his team discovered a discrepancy that helps explain why parents often rate a child’s social impairment to be greater than the child does: When it comes to social skills, parents view self-control as crucial, whereas children see cooperation as more important. That gap in particular can actually guide clinicians making treatment decisions.

In a 2012 study, Lerner and his colleagues asked 53 teens with autism and their parents to describe the teens’ social ability. They found that when parents saw their children’s skills as much worse than their children did, those children benefited the most from programs designed to build social confidence, and showed significant decreases in social anxiety.

A small gap between the parents’ and children’s perspectives, on the other hand, predicted depression in the teenager.

In Lerner’s view, that finding lends credence to a larger theory — the so-called self-protective hypothesis, borrowed from the literature on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. The premise is that people overrate their abilities when they are trying to shield themselves from the pain of acknowledging a weakness. By that logic, if they acknowledge that their social skills are poor, they are not protecting themselves and may need additional support.

Even when people protect themselves and provide inaccurate self-reports, that perspective is valuable. For instance, self-reports have shown that teens with autism may not realize or acknowledge when they are being bullied or teased by their peers. “In some ways, that’s really protective, if you don’t think other people are picking on you,” says Somer Bishop of the University of California, San Francisco. “But it can also make you really vulnerable.” Those vulnerabilities are important for a clinician to know about.

“Really good clinicians are often already thinking about this stuff,” Lerner says. But he hopes his work will encourage more of them to ask people with autism about their experiences.

”“I think the idea that we can interpret someone’s behavior without asking them [questions] is just not fair.” Vanessa Bal

Assessing adults:

P

sychologists at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s TEACCH Autism program routinely use self-report tools with adults on the spectrum. But the program’s staff have noticed a problem: Caregivers, including parents, siblings, close friends or spouses, tend to describe the adults’ difficulties as more severe than the adults themselves do.“It’s not clear whether one reporter is more accurate than the other,” says Laura Klinger, the program’s executive director. A person with autism might minimize or misunderstand a difficulty, but a loved one might equally misinterpret the magnitude of the problem out of concern.

The researchers are trying to work out whether self-report tools come up short in this domain. In an ongoing study, they are looking at a range of self-reports from 40 adults with autism, all of average or above-average intelligence and who have had a diagnosis since childhood. The participants and their caregivers answer a battery of questions about their social life, daily experiences and quality of life, among other topics.

The preliminary results suggest that caregivers and adults with autism often agree on the severity of their autism features, such as repetitive behaviors.

But caregivers are more likely to notice problems the adults with autism may have with daily living activities, such as maintaining a tidy home or keeping up on their finances. Klinger has found that these activities are predictors of successful employment and quality of life. But if adults on the spectrum can’t describe these challenges using the existing self-report tools and pass self-report ‘daily living’ assessments with flying colors, they may not qualify for job coaching or other support in the home or workplace. “I want to make sure [adults with autism] have the tools to be the best possible advocates for themselves,” says Rachel Sandercock, a graduate student in Klinger’s lab.

Self-assessments may also help to untangle how people with autism experience conditions such as anxiety or sleep deprivation differently from their typical peers. To that end, Amanda Richdale of La Trobe University in Australia is using multiple self-assessments to study large groups of young adults with autism. “Obviously, questionnaires are only a place to start, but they’re a really good place to start because the findings can lead to more detailed experimental studies,” she says.

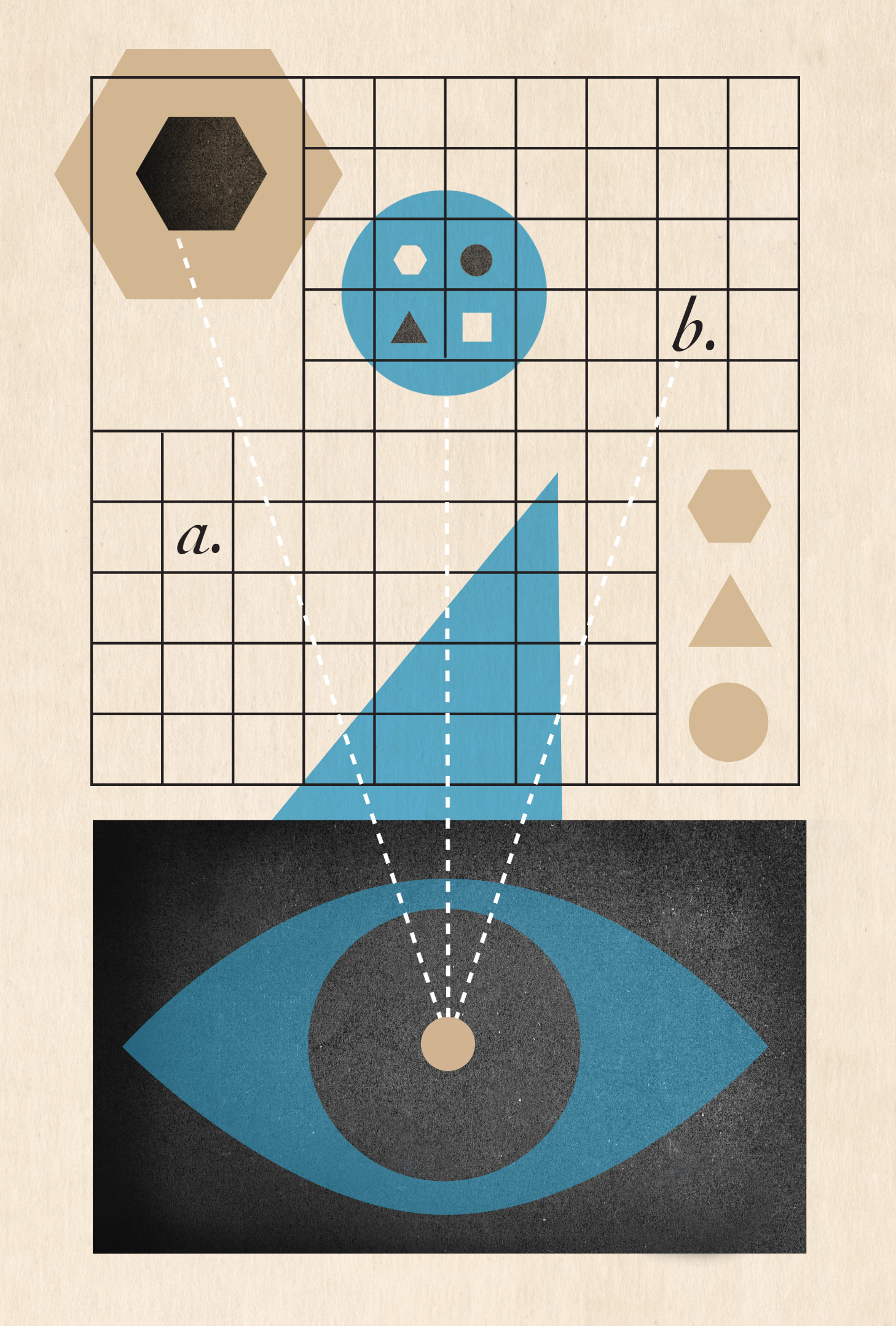

Richdale says a broader variety of self-assessments is needed: “I think we could even do more in trying to get self-report from people who are less able.” Visually driven assessments — such as the color-coded scales doctors use to ask people to rate pain — could help nonverbal individuals communicate their experiences. To reach people at the severe end of the autism spectrum, researchers might also adapt quality-of-life measures developed for the intellectually disabled, which draw on careful observations of a person’s behavior over time.

Many autism researchers echo this call for more and improved self-report assessments — a sign that the field is maturing, Kanne says. “Never did I sit down and go, ‘I’m going to develop the best self-report measure.’” Back then, he says, “none of us thought that way.”

Since Lerner launched his drama-based program 14 years ago, the question has shifted from whether scientists should ask people with autism about themselves to how. “The notion that people with autism are just wrong about themselves all the time struck me as implausible,” he says. Now the research has caught up with his impression: People with autism are often the best judges of their own experience.

Syndication

This article was republished in Scientific American.

Recommended reading

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

PTEN problems underscore autism connection to excess brain fluid

Explore more from The Transmitter

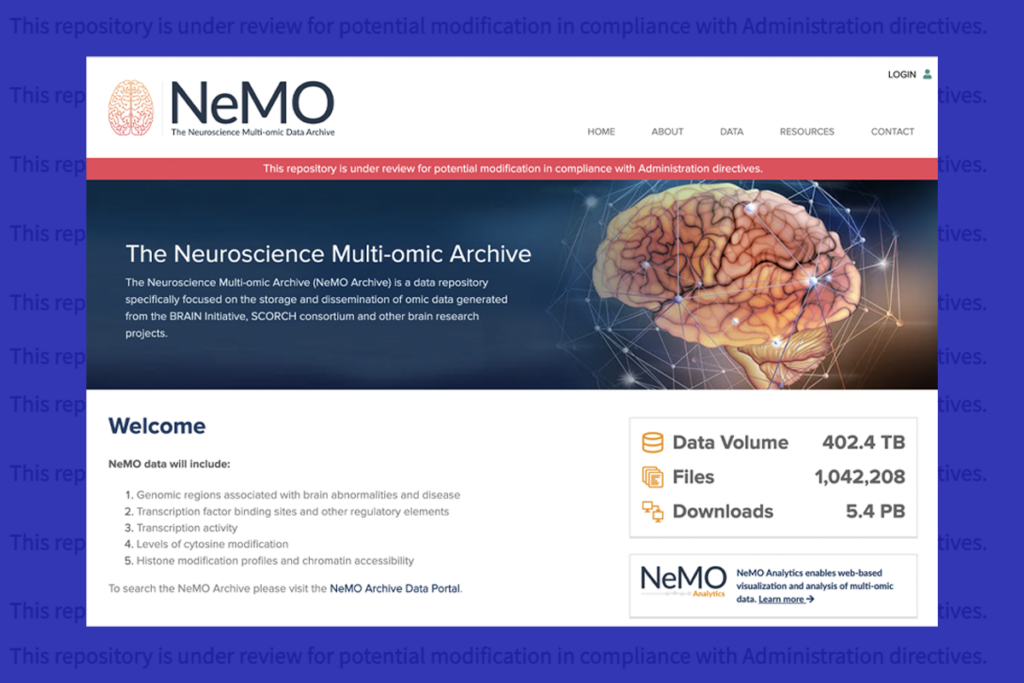

U.S. human data repositories ‘under review’ for gender identity descriptors