Anxiety may alter processing of emotions in people with autism

A brain region that processes emotions tends to be smaller in children who have both autism and anxiety than in those who have autism alone.

A brain region that processes emotions, including fear, tends to be smaller in children who have both autism and anxiety than in those who have autism alone, according to a new study1.

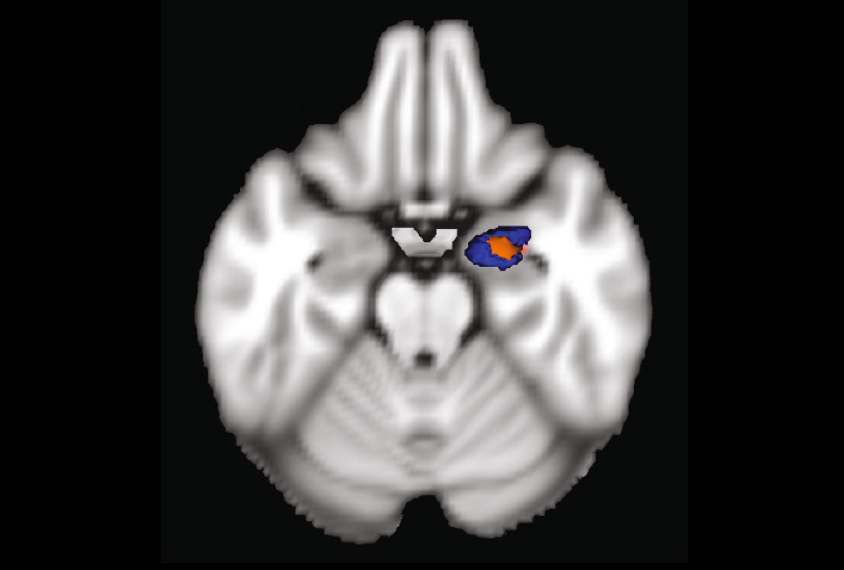

The findings suggest that the difference in volume of this region, called the amygdala, is related to how these individuals process emotions.

The amygdala is thought to be involved in autism, but exactly how has been unclear. Some studies have reported that it is larger in children with autism than in controls and perhaps normalizes later in life — but others have shown that it is smaller.

The new work suggests that the amygdala’s size depends on whether the children also have anxiety. Anxiety is also associated with a small amygdala in typical individuals2.

“It is no longer sufficient to say, ‘Is the amygdala different in children with autism?’ The question you have to start asking is, ‘What components of autism are related to the amygdala?’” says lead researcher John Herrington, assistant professor of psychology in psychiatry at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Roughly 40 percent of children with autism have anxiety, although some studies put this number much higher. It is not clear whether a small amygdala contributes to autism and anxiety or results from these issues.

Either way, the findings underscore the importance of grouping children with autism by relevant features. “The heterogeneity of autism is discussed often, so it is really good to see a study that takes the approach of subgrouping children,” says Christine Nordahl, assistant professor psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute, who was not involved in the study.

Right size:

Herrington’s team used magnetic resonance imaging to measure the volume of various brain regions in 53 children with autism, 29 of whom have anxiety, ranging in age from 7 to 17 years. They also scanned 37 controls matched for age and intelligence. The work is part of a larger study aimed at finding biological indicators of anxiety in children with autism.

The researchers diagnosed anxiety using a clinical questionnaire, the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule, along with an ‘addendum’ that accounts for autism features that may mask or mimic features of anxiety.

The children with autism show no difference in amygdala volume when compared with controls. But the subgroup of children with autism and anxiety have smaller amygdala on the right side of the brain than the other children with autism. Why the difference appears only on the right is unclear. The results appeared 8 July in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

The findings suggest that researchers should take anxiety into account when studying autism.

“Talking about an ‘autism brain’ misses out on those who do or do not have anxiety,” says Mikle South, associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, who was not involved in the study.

Scientists should look for amygdala changes in children with autism who have atypical forms of anxiety, such as intolerance of uncertainty, South says. Herrington’s team excluded 10 children who have only this type of anxiety, which is often seen in people with autism.

Scientists should also focus on amygdala size across development, says Cynthia Schumann, associate professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the MIND Institute, who was not involved in the study. Other work has shown that the volume of the amygdala changes as children get older; the new study grouped together children across a wide age range.

The researchers plan to investigate whether certain parts of the amygdala underlie the region’s connection to autism and anxiety.

References:

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt