Regions of the amygdala are enlarged in autistic children and teenagers with anxiety, but not in their autistic or non-autistic peers without anxiety, a new study finds.

The structure — which consists of almond-shaped clusters of neurons in each brain hemisphere — helps to assess threats and process fear. It typically grows throughout childhood and into adulthood, but in those with autism this growth speeds up in childhood and plateaus in adolescence, previous imaging studies indicate.

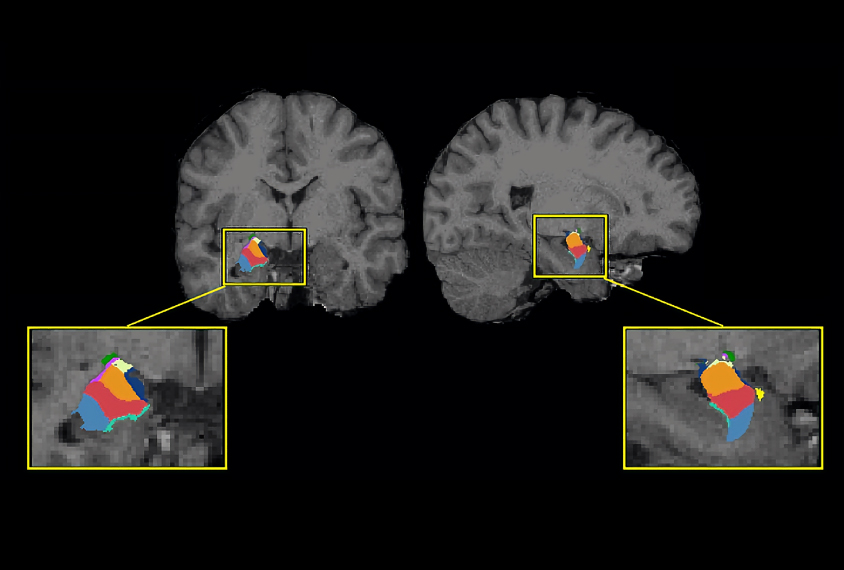

The new findings suggest the amygdala differences seen in some autistic people may have more to do with anxiety than with autism, and they point to specific sections of the amygdala, known as subnuclei, says lead investigator Emma Duerden, assistant professor of applied psychology at Western University in London, Canada.

Earlier studies implicated one subnucleus, known as the central amygdala, in anxiety in animal models. Its size also tracks with anxiety scores in youth with autism and those with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), but not in those with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Duerden and her colleagues found. Future work should explicitly focus on autistic children with and without anxiety to clarify the association with the central amygdala, she says.

Replication attempts can also hopefully add clarity, says Deyou Zheng, professor of genetics, neurology and neuroscience at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York City, who was not involved in the study, because the volume changes measured in this study are small.

“And, obviously,” he says, “we can’t tell if the enlargement of specific amygdala subregions contributes to autism and anxiety or [is] the adaption consequence of increased anxiety.”

D

uerden and her team recruited 5- to 18-year-olds through clinics across Ontario, Canada. Among the 233 participants, 101 have autism, 37 are neurotypical, 59 have ADHD and 36 have OCD. Clinicians confirmed each participant’s diagnosis or lack thereof, and parents reported on their children’s anxiety levels using a clinical questionnaire. On average, participants with autism or OCD had a significantly higher anxiety score than those with ADHD and more than five times the score of the neurotypical group.Participants with autism or OCD who had higher anxiety scores also had a larger central amygdala in the brain’s right hemisphere than did neurotypical participants and those with ADHD, the team found using MRI. The central amygdala is the structure’s main output, setting off an alarm that activates the brain’s stress response. The volume of another subnucleus, the anterior amygdaloid area, also increased with anxiety scores in participants with autism and OCD, but not neurotypical participants or those with ADHD. Anxiety showed no relationship with the volumes of the left amygdala subnuclei.

The exact role of the different subnuclei in anxiety is unclear, but the central amygdala’s role makes it a promising candidate for further study, Duerden says. The work was published in Human Brain Mapping earlier this month.

Whereas previous work has shown that amygdala size is related to anxiety in autistic children, the new findings suggest the amygdala plays an important role in anxiety independent of autism, including in those with OCD. Participants with ADHD had somewhat elevated anxiety compared with neurotypical participants, but the sizes of their subnuclei were more typical and bore no significant relationship to anxiety, indicating that the association may not hold across various neurodevelopmental conditions.

B

ecause the researchers scanned people with different conditions and neurotypical people all on the same scanner, they avoided the problems that arise in many large neuroimaging studies that use different scanners, software and procedures across sites, says Christine Wu Nordahl, professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of California, Davis MIND Institute, who was not involved in the study. “It’s a monumental effort, what they’ve done to collect this data.”And the study’s focus on amygdala subnuclei is much-needed, says David Amaral, distinguished professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the MIND Institute, who was not involved in the work, but “we’re just somewhat cautious about whether the curent tools can adequately define these regions that are very difficult to define.”

In a study published in June, Nordahl and Amaral linked anxiety traits to amygdala size in autistic people and suggested that autism-specific anxiety — such as that around disruptions to special interests or routines — looks different from generalized anxiety in the brain. Generalized anxiety, they found, is associated with a larger-than-average right amygdala, consistent with Duerden’s team’s findings, but autism-specific anxiety is linked to a smaller-than-usual one.

In the new study, the two autism subgroups may cancel each other out, leading to somewhat smaller overall effects, Nordahl says.

Because the new work relies on parent reports, it cannot distinguish between generalized anxiety and autism-specific anxiety, Duerden says. In a paper currently under review, Duerden and her team compared amygdala subnuclei size and parent- and self-reports for a different cohort of autistic and non-autistic children, all with an anxiety diagnosis.

“Anxiety is real, and it is associated with changes in the brain,” Duerden says. “For many individuals who are on the spectrum, and other children who are impacted by anxiety, they’re often told these are just feelings.”

The new work could help pave the way for targeted treatments, Duerden says. Anxiety therapies are less effective for autistic people than for their neurotypical peers, even though estimates suggest that roughly 40 percent of young people with autism have anxiety disorders, compared with about 27 percent of neurotypical children.