Analysis spotlights mutations in ‘dark’ regions of the genome

Whole-genome scans of nearly 8,000 people link autism to spontaneous mutations in the stretches of DNA that regulate genes.

Spontaneous mutations in stretches of DNA between genes contribute to autism, a robust new analysis of nearly 8,000 whole genomes suggests1. These mutations are present in promoters, the segments that abut genes and control their expression.

The work stops short of identifying individual mutations, but it provides a starting point for further analysis. Researchers published the findings today in Science.

Scientists have typically hunted for autism mutations within genes, but the vast majority of human DNA lies between genes. This DNA was once dismissed as unimportant, but over the past five years, researchers have begun to search through it for mutations linked to various conditions, including autism.

Figuring out which mutations in these regions are harmful and why is a big challenge, says lead researcher Stephan Sanders, assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. This is because it is difficult to find a relevant variant among the hordes present across the whole genome.

Sanders’ team devised a multistep computational approach to clear this hurdle. “The big message is that this is a tractable problem with current technology,” he says.

The team hit upon a promising way to focus on a few regions of interest within the genome, says Lucia Peixoto, assistant professor of biomedical sciences at Washington State University in Spokane, who was not involved in the study. `

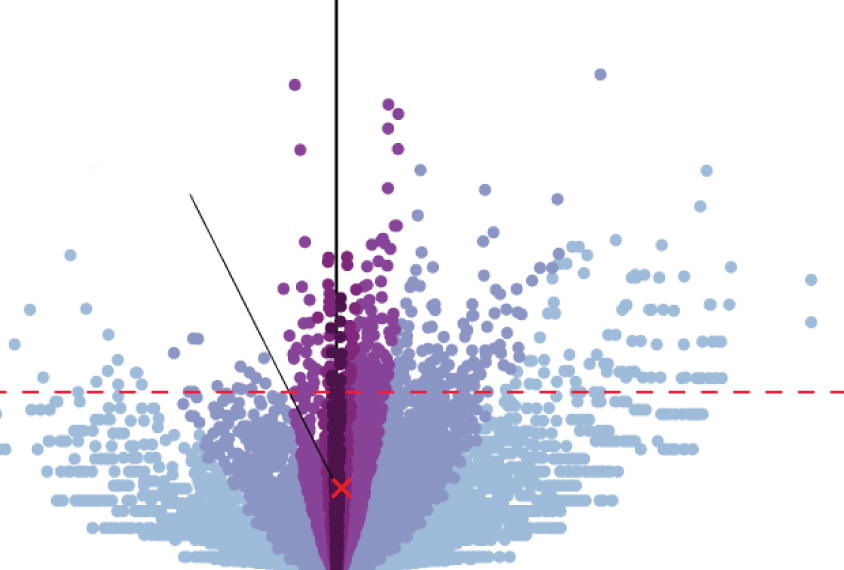

“You have a problem if you look everywhere, because a huge proportion of the genome is not really going to have a signal,” she says.

Needles in a haystack:

In May, Sanders’ team described a way to link noncoding variants to autism with no prior assumptions about which regions might be important. They came up with about 52,000 possible categories of noncoding variants that could be involved in autism.

They looked for links between variants in these categories and autism in 519 families but did not find a credible signal.

In the new study, they used the same technique in 1,902 families with one autistic child and one typical child. They focused on variants that arise spontaneously, or de novo.

Again, they did not find a statistically significant signal. The team then used a machine-learning approach to link variant types to autism.

This new analysis linked 163 types of noncoding variants from the 519 families to autism. Of the 163 categories, 45 include promoters — defined as the 2,000 base pairs closest to the beginning of a gene. Promoters appeared in the categories more than twice as often as would be expected by chance.

A noncoding variant in one of these promoters predicted autism in the remaining 1,383 families. (The team presented some of this work in May at the 2018 International Society for Autism Research annual meeting in Rotterdam, the Netherlands.)

Findings to function:

The researchers then looked at which of these promoter regions are mutated more often in the children with autism than in their siblings. They found that promoter regions that are preserved across species — that is, conserved throughout evolution — show more mutations among the autistic children.

The genes these promoters control tend to regulate the expression of other genes or play a role in development. The next step is to narrow these broad functional categories to specific types of genes, including those linked to autism, Sanders says.

The findings make sense because many autism genes are known to control other genes, says Jonathan Sebat, professor of psychiatry and cellular and molecular medicine at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the study.

“[This study is] really drilling down more deeply into the specific interactions,” he says.

In a study published earlier this year, Sebat and his colleagues linked a different type of genetic variant in promoters to autism.

The study is large, but to link specific noncoding variants to autism, researchers will need to analyze thousands more whole genomes, says Yufeng Shen, assistant professor of systems biology and biomedical informatics at Columbia University.

“This highlights the importance of expanding sample size to improve statistical power,” Shen says.

References:

- An J. et al. Science Epub ahead of print (2018) Full text

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt