Analysis of single cells implicates set of neurons in autism

A set of neurons involved in complex cognitive functions may play a central role in autism.

The first analysis of single cells from the brains of autistic people homes in on a group of neurons as central to autism1.

These neurons are involved in communication between brain regions that mediate higher-order cognitive abilities, such as social and language skills.

The study also reveals a potentially important role for microglia, the brain’s immune cells.

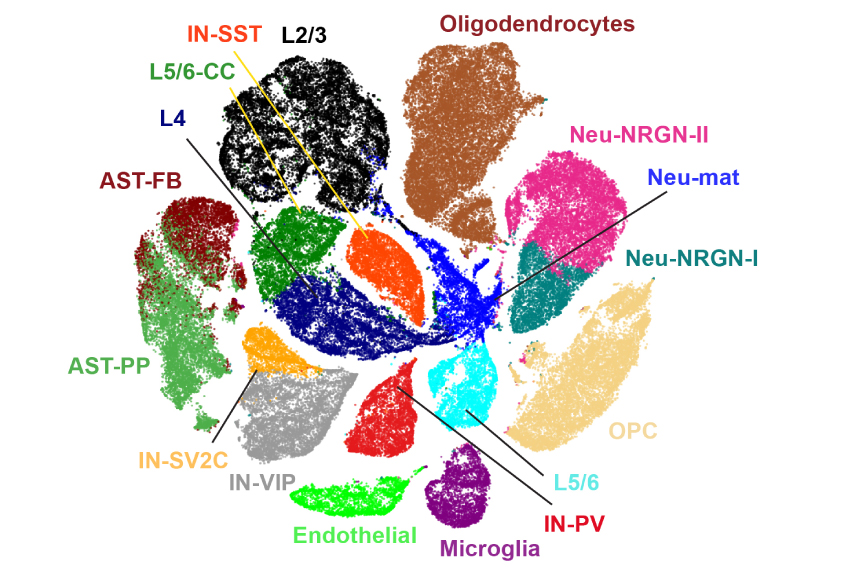

The findings, published last week in Science, are based on data from more than 100,000 cells from 15 autistic people and 16 controls.

They suggest that the diverse forms of autism stem from shared alterations to certain cells, says lead researcher Arnold Kriegstein, professor of neurology at the University of California, San Francisco.

“We were able to see consistent changes and vulnerable cell types,” he says. “There may well be a convergence on a particular subset of neurons.”

The researchers relied on a new technique that enables them to sequence RNA — the transcripts of genes — from individual cells in postmortem brains. They were previously only able to analyze clumps of tissue.

The study offers “a potentially transformative insight into autism spectrum disorder and what cell-type-specific changes might be occurring,” says Tomasz Nowakowski, assistant professor of anatomy at the University of California, San Francisco, who was not involved with the study. “This is just a tip of the iceberg as we start to utilize these technologies more and more.”

Direct connection:

Kriegstein and his colleagues sliced thin sections from the brains. They took slices from two parts of the cerebral cortex that control complex social and other cognitive functions. Neurons in the cerebral cortex are organized in six layers, and the researchers tried to sample each layer equally. The researchers then isolated each cell’s nucleus and sequenced the RNA. They controlled for the effects of seizures, which are common among autistic people.

They found that 513 genes overall are expressed at either higher or lower levels in autism brains than in controls; 26 of these are top autism genes. Neurons with the most altered genes, including autism genes, are in layers 2 and 3. And those genes tend to be under-expressed.

These cells connect to other cells across the cerebral cortex to form networks governing various aspects of cognition. The team presented their findings last year at the 2018 Society for Neuroscience annual meeting in San Diego, California.

The link to this specific set of cells is striking, some experts say, because other studies have implicated these neurons in autism. For example, another single-cell sequencing study, presented earlier this month at the 2019 International Society for Autism Research meeting in Montreal, also implicated layer 2 and 3 neurons.

“I’m impressed by the finding that there seems to be a very robust signal in a specific cortical layer despite the number of cases and the presumed heterogeneity of cases,” says Matthew Anderson, associate professor of pathology at Harvard University, who was not involved with the study.

Central cells:

A 2013 study reported that many autism genes tend to be expressed in layer 2 and 3 neurons during mid-fetal gestation — thought to be a key period in autism’s genesis.

“There is potentially now a direct connection between the genetic risk for the condition and the molecular pathology,” says Daniel Geschwind, professor of neurology and psychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles, who led the 2013 study and the one presented in May.

Kriegstein’s team also saw gene-expression signals in other brain cells. Some of the biggest differences showed up in microglia and astrocytes, star-shaped cells that support neurons.

The differences in both neurons and microglia track with autism severity, based on scores on the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised.

Some researchers say they are skeptical of the findings because the number of brains is too small to represent autism’s diversity.

“The design presumes from the start that ‘autism’ is a single thing, when we know very clearly that it isn’t,” says Kevin Mitchell, associate professor of genetics at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland. “There is no reason to think that autism is acutely dependent on some particular profile of gene expression in some particular cells.”

The authors plan to repeat their work analyzing more brains and in regions outside the cerebral cortex.

References:

- Velmeshev D. et al. Science 364, 685-689 (2019) PubMed

Recommended reading

Too much or too little brain synchrony may underlie autism subtypes

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Shane Liddelow on two papers that upended astrocyte research

Dean Buonomano explores the concept of time in neuroscience and physics