Analysis finds no evidence for popular autism communication method

A comprehensive review has found no scientific basis for a controversial technique that supposedly helps autistic people communicate.

A comprehensive review has found no scientific basis for a controversial technique that supposedly helps autistic people communicate1.

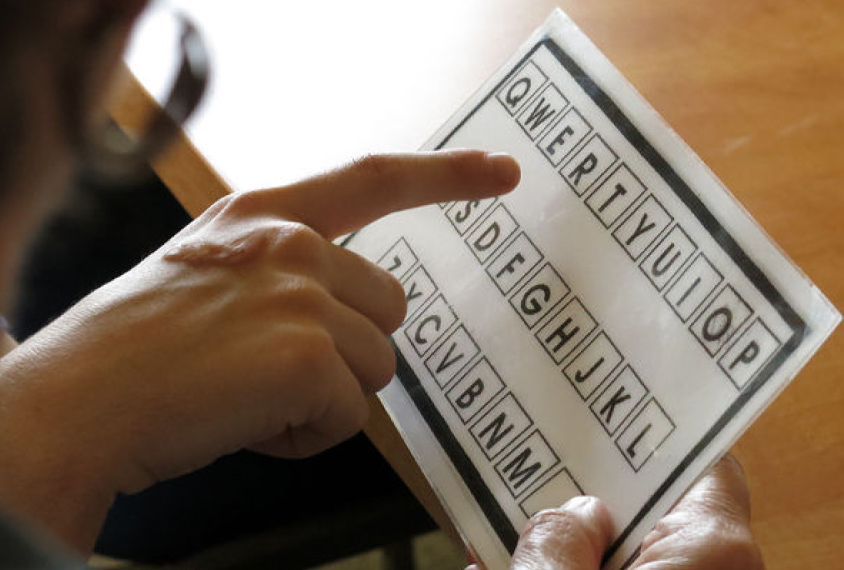

In the ‘rapid prompting method,’ a person trained in the technique holds an alphabet board or a tablet and, using words or gestures, prompts an autistic person to point to or tap letters, words or pictures.

The method resembles a discredited technique, called facilitated communication, in which a person applies pressure to the hand or arm of an autistic person to help her share her thoughts via a board or tablet. A string of rigorous studies, dating back to the 1990s, has shown that messages created by facilitated communication are almost always controlled by the facilitator — sometimes with harmful consequences.

Rapid prompting also requires the help of another person, although unlike in facilitated communication, the helper does not physically apply pressure.

Given the similarities between the two techniques, however, experts have long urged caution against using the rapid prompting method until its safety, validity and effectiveness are proven. It is possible, they say, that the facilitator influences the messages — intentionally or not — by moving the communication device or through subtle cues.

“It’s absolutely critical to do such a rigorous test like what occurred for facilitated communication,” says Ralf Schlosser, professor of communication sciences and disorders at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, who led the new study. “The time that goes into using a technique that is not supported takes away time from legitimate interventions.”

Soma Mukhopadhyay, the mother of a nonverbal man with autism, created the rapid prompting method for her son nearly 30 years ago and has since taught it to hundreds of others. Experts say they are troubled that the method has gained traction among families and in schools.

“It’s all being used on the basis of anecdotal evidence and zero science, according to this review,” says Pat Mirenda, professor of educational and counselling psychology and special education at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, who was not involved in the study. “That’s really problematic.”

No validity:

Roughly one in four autistic people speaks few or no words. To help these people express themselves, speech-language pathologists often use augmentative and alternative communication. This type of therapy includes any of various tools and methods designed to stand in for or supplement speech — such as the speech generator that responded to cheek twitches from the late physicist Stephen Hawking.

Unlike rapid prompting and facilitated communication, these tools do not require a facilitator and lead to independent communication, and professional organizations such as the American Speech-Hearing-Language Association support their use.

Schlosser and his colleagues scoured scientific databases for studies of the effectiveness of the rapid prompting method for autistic people. They found 108 studies that mention the method, but none met their criteria for a valid test of a therapy. They reported their results in May in the Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders.

“There’s no scientific validity to [rapid prompting],” says Diane Paul, director of clinical issues in speech-language pathology at the American Speech-Hearing-Language Association, who was not involved in the study. “It hasn’t been demonstrated to lead to independent communication, and it’s very prompt-dependent.”

Paul says an early version of the new study led her association to recommend against the use of rapid prompting, in a policy statement released August 2018. The American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities also disavows the technique.

The new study “meets the highest standard” of scientific rigor, says Oliver Wendt, assistant professor of communication sciences and disorders at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, who was not involved in the work. “There should be many more experimental studies on the rapid prompting method.”

Wendt, Schlosser and others acknowledge that the lack of evidence does not mean the method is ineffective. Rather, the findings highlight the need for studies to determine who generates the messages produced during rapid prompting. If those studies suggest that the method reliably relays the thoughts of the autistic person rather than of the facilitator, the experts say, the next step would be to test whether the technique improves the autistic person’s communication skills.

References:

- Schlosser R.W. et al. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. Epub ahead of print (2019) Abstract

Recommended reading

Developmental delay patterns differ with diagnosis; and more

Split gene therapy delivers promise in mice modeling Dravet syndrome

Changes in autism scores across childhood differ between girls and boys

Explore more from The Transmitter

Smell studies often use unnaturally high odor concentrations, analysis reveals

‘Natural Neuroscience: Toward a Systems Neuroscience of Natural Behaviors,’ an excerpt