Amygdala and autism’s checkered history

To understand the amygdala’s role in autism, researchers should study its connections with other brain structures and explore its role in development, says Ralph Adolphs.

What’s more, there are intriguing similarities in how people with autism and individuals who have rare lesions, or damage to the amygdala, make eye contact and judge emotions when looking at particular regions of faces: Both measures are reduced in both groups compared with controls2, 3, 4. Studies have also linked abnormal eye fixations in autism to abnormal functional activation of the amygdala5, 6.

On the other hand, the functional imaging literature is by no means in unanimous agreement that people with autism show abnormal amygdala activation. Nor do amygdala lesions in people lead to behavioral symptoms that come close to meeting the diagnostic criteria for autism7.

Adding to the confusion, dysfunction has been reported all over the brain in autism, certainly not disproportionately in the amygdala8. And the amygdala has in turn been implicated in nearly every psychiatric disorder9, 10.

None of this crosses the amygdala off our list of structures that are important for understanding autism. Instead, it suggests a more sophisticated and nuanced view in two ways. First, we need to look at connections between the amygdala and other brain structures, situating its role in a circuit. Second, we need to understand the amygdala’s role in development.

Brain connections:

A role for pathology involving any single structure, such as the amygdala, seems initially hard to reconcile with the popular view of autism as a disorder of brain connectivity11.

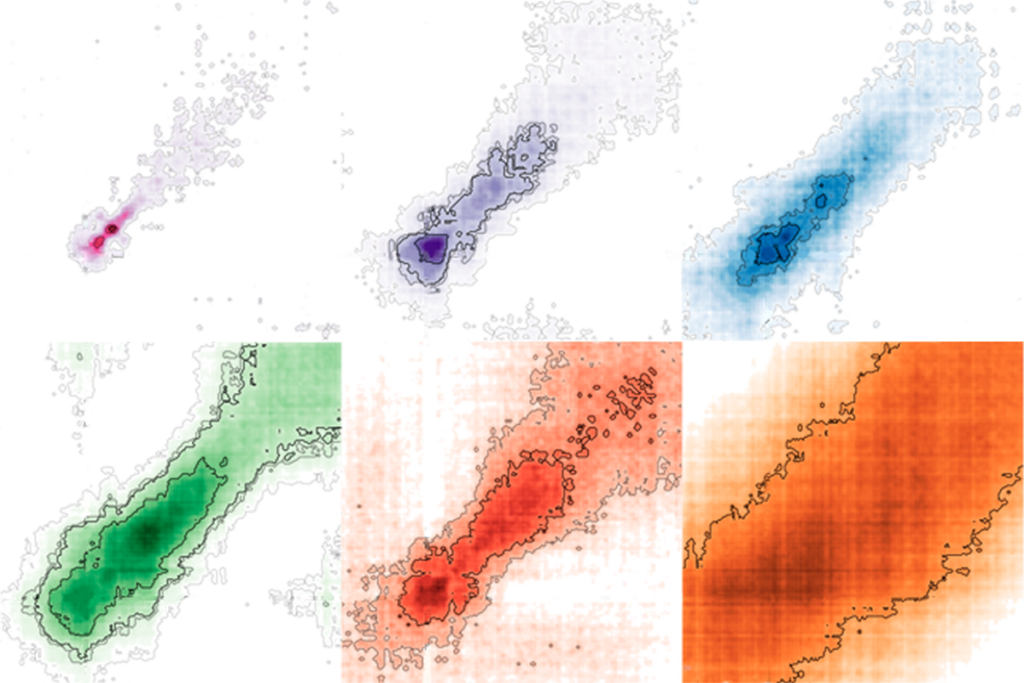

However, a study published last year showed that autism brains at rest have reduced functional connectivityparticularly in the amygdala, as well as in other structures thought to participate in social cognition12. Functional connectivity measures infer how strongly two brain structures communicate with each other by analyzing functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data acquired while participants are lying inside the scanner and not actively engaged in any task (hence they can be used even in infants).

Abnormalities in amygdala connectivity in infancy may also predict the later emergence of autism13 bringing us to the crucial topic of development.

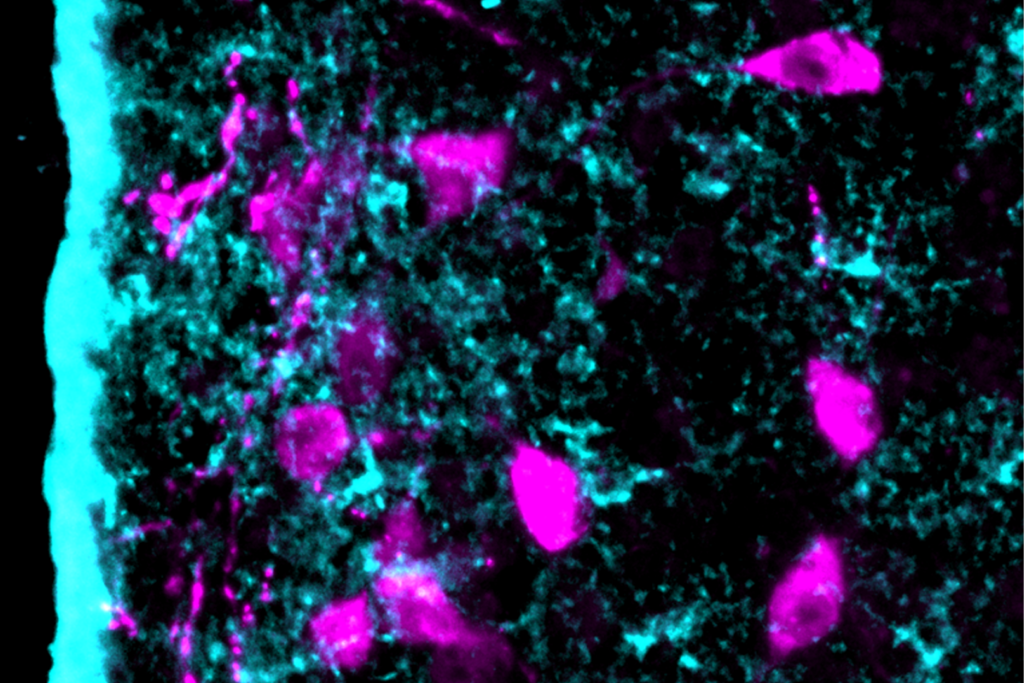

Several MRI studies suggest we should pay closer attention to amygdala development, which features a remarkably protracted period of structural changes that occur throughout infancy, childhood and adolescence. Alterations in this developmental trajectory have been found in autism, where there is an initial abnormal enlargement of the amygdala in childhood that normalizes in adulthood14, 15.

It is noteworthy that an enlarged amygdala in autism may be hyperactive, whereas a damaged amygdala would be the opposite.

The next challenge is to provide more specificity to the above picture: Given that the amygdala is one of the most densely connected structures in the brain, does it make fewer overall connections in autism, or are there specific connections with other brain regions that are missing?

Of particular interest are the many connections between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala, which change throughout typical childhood and adolescence16. These connections have been linked to an exaggerated response of the amygdala to faces in both children17 and adults18 with autism. This may be due to a decrease in habituation of the fMRI response over time. The prefrontal cortex normally dampens amygdala responses over multiple trials, but fails to do so in autism.

A role for abnormal connectivity between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex in the development of autism also fits well with theories of early alterations in social reward and social motivation19. Connections between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala have long been shown to be important for these functions.

Key context:

Results implicating specific circuits should not detract from investigating the many other structures that contribute to autism, but they will help add one component into which researchers can sink their teeth. What is the precise functional contribution of this particular circuit to autism?

Studies of mood disorders suggest that the prefrontal cortex serves to regulate the emotional responses triggered by the amygdala. This model is supported by the gradual loss of fear conditioning in experimental studies of this same circuit, in a large number of experiments ranging from rat electrophysiology to human fMRI.

The amygdala can orchestrate cognitive processes based on social stimuli, but it requires information about the context in which those stimuli occur — information conveyed by the prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus. In the absence of such contextual input, the amygdala may inappropriately interpret social stimuli, which may become ambiguous and overwhelming. The long-term effects of the concomitant anxiety and avoidance could add to social deficits.

Three features make investigations of the amygdala’s role in autism particularly exciting. First, the amygdala’s structure develops over time. This, paired with its well-studied role in emotional learning, raises the hope that interventions could target the amygdala’s role in development.

Second, calls for understanding psychiatric disorders across a spectrumfit well with our emerging view of the amygdala in motivation and reward. This role will surely cut across multiple disorders, and may help to parse subtypes of autism.

Finally, animal studies are rapidly revealing the intricate details of the amygdala’s connectivity, as well as more precise descriptions of its multiple behavioral roles. Techniques such as optogenetics, which uses light to activate neurons in the brain, can carve out circuits that elude the resolution possible with fMRI.

Putting all these pieces together will take some time, and will surely show us that ‘the amygdala’ and ‘autism’ are concepts that need substantial revision before we can properly relate them to each other.

Ralph Adolphs is Bren Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience at the California Institute of Technology.

References:

1. Damasio A.R. and R.G. Maurer Arch. Neurol. 35, 777-786 (1978) PubMed

2. Pelphrey K.A. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 32, 249-261 (2002) PubMed

3. Adolphs R. et al. Nature 433, 68-72 (2005) PubMed

4. Spezio M.L. et al. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 929-939 (2007) PubMed

5. Dalton K.M. et al. Nat. Neurosci. 8, 519-526 (2005) PubMed

6. Kliemann D. et al. J. Neurosci. 32, 9469-9476 (2012) PubMed

7. Paul L.K. et al. J. Neurodev. Disord. 2, 165-173 (2010) PubMed

8. Amaral D.G. et al. Trends Neurosci. 31, 137-145 (2008) PubMed

9. Schumann C.M. et al. Neuropsychologia 49, 745-759 (2011) PubMed

10. Kennedy D.P. and R. Adolphs Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 559-572 (2012) PubMed

11. Geschwind D.H. and P. Levitt Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 17, 103-111 (2007) PubMed

12. Gotts S.J. et al. Brain 135, 2711-2725 (2012) PubMed

13. Wolff J.J. et al. Am. J. Psychiatry 169, 589-600 (2012) PubMed

14. Nordahl C.W. et al. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 69, 53-61 (2012) PubMed

15. Schumann C.M. et al. J. Neurosci. 24, 6392-6401 (2004) PubMed

16. Gee D.G. et al. J. Neurosci. 33, 4584-4593 (2013) PubMed

17. Swartz J.R. et al. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 52, 84-93 (2012) PubMed

18. Kleinhans N.M. et al. Am. J. Psychiatry 166, 467-475 (2009) PubMed

19. Chevallier C. et al. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 231-239 (2012) PubMed

Recommended reading

New autism committee positions itself as science-backed alternative to government group

Astrocytes orchestrate oxytocin’s social effects in mice

Explore more from The Transmitter

Let’s teach neuroscientists how to be thoughtful and fair reviewers

Two neurobiologists win 2026 Brain Prize for discovering mechanics of touch