Alternative screen finds high autism prevalence in U.S. state

A new study in South Carolina has found a prevalence of 3.62 percent for autism, or roughly 1 in 28 children.

A new study in South Carolina has found a prevalence of 3.62 percent for autism, or roughly 1 in 28 children. Researchers presented the unpublished findings today at the 2017 International Meeting for Autism Research in San Francisco, California.

The study screened children born in 2004, the same birth year analyzed in the most recent prevalence estimate by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). For South Carolina, that estimate, released in 2014, reported a prevalence of 1 in 81 children1. The average prevalence for the United State is 1 in 68.

These striking differences stem from the fact that the researchers met many of the children to assess them for autism, instead of relying on existing assessments, says lead researcher Laura Carpenter, professor of pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina.

“I think this is probably getting pretty close to the true prevalence,” Carpenter says. “This is probably going to make a lot of sense for anybody who is working in a school or autism clinic.”

The new work is modeled after a similar prevalence study in South Korea that found an autism rate of 2.65 percent, more than twice the U.S. rate at that time.

It’s not surprising that the method the new study used yielded a higher prevalence rate even in a U.S. state, says Young Shin Kim, who led the South Korea study.

Two steps:

To assess prevalence, the CDC typically looks at the school and medical records of every child in a specific district. In the new study, by contrast, researchers sent an autism questionnaire to schools in three counties in South Carolina. The researchers then examined a subset of the children who screened positive, using several autism diagnostic measures.

The advantage of this approach is that it may pick up children who don’t have an official assessment of autism in their records. For example, a therapist might assess a child for a related condition, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but not note any autism-related features, says Carpenter.

The downside is that the method does not look at every child in the region. The researchers sent the screen, the Social Communication Questionnaire, to 8,780 families from 123 of 127 schools in the region, as well as 25 home-school networks and 3 virtual schools. Fewer than half the families, or 4,185, returned the screen.

The researchers invited all 274 children who scored above the cutoff for autism for an in-person assessment. They also invited 584 children who scored in the borderline range. Of all these children, only 292, or 34 percent, agreed to participate.

Such a big drop-off in participation can skew the findings, says Maureen Durkin, professor of population health sciences at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not involved in the study. For example, parents who are concerned that their child has autism may be more motivated to participate, she says.

“Unless you assume that those who didn’t participate have the same rate of autism as those who did, there is real potential for selection bias,” she says. “The one thing about selection bias is it’s by definition unknowable. I can’t say this is definitely an overestimate, because I really don’t know.”

Diagnosed subset:

Carpenter agrees that the low response rate is of concern but notes that the numbers could also go the other way. For example, families who already know their child has autism may not be motivated to take the time for yet another assessment.

What’s more, the demographic profile of the families who were sent the screen roughly matches that of the families who responded and those who came for the assessment — suggesting that the proportion who came for assessment are representative of the broader population.

This finding is “encouraging,” says Durkin. “That’s a strength.”

The study found that of the 292 children assessed in person, 52 children, including 7 girls, have autism, and 16 of them did not have a prior diagnosis. All but 2 of the 16 children had been diagnosed with other conditions such as ADHD or anxiety.

Of the 52 children, 21 percent have intellectual disability, lower than the CDC estimate of 32 percent. This may be because the new method is better suited to catching children with intelligence quotients of average or above, says Carpenter.

For more reports from the 2017 International Meeting for Autism Research, please click here.

References:

- Christensen D.L. et al. MMWR Surveill. Summ. 65, 1-23 (2016) PubMed

Recommended reading

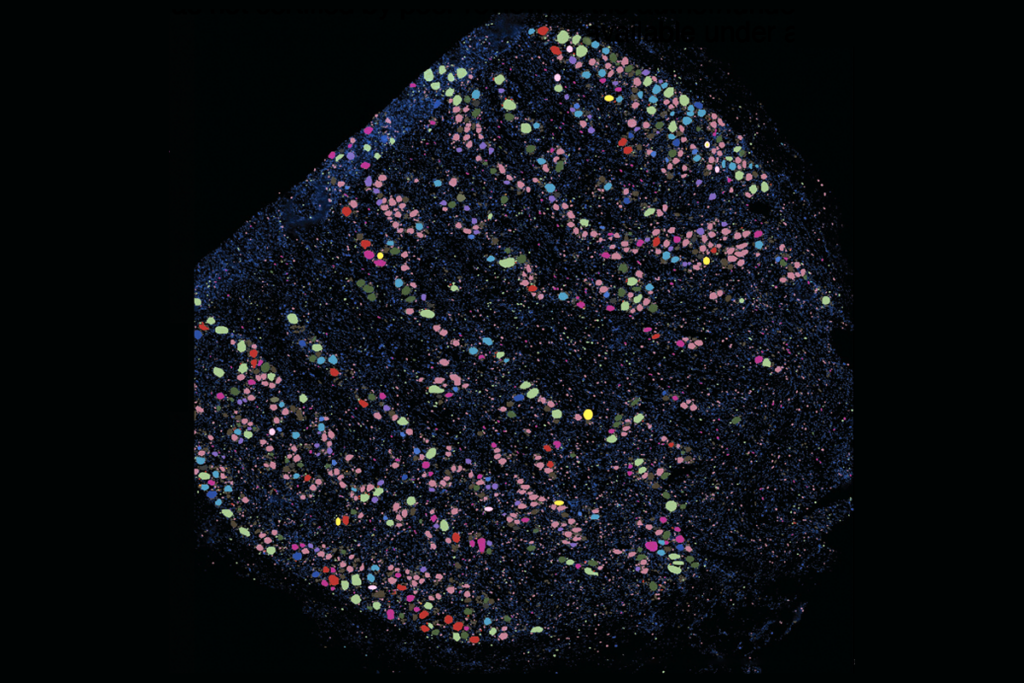

New organoid atlas unveils four neurodevelopmental signatures

Glutamate receptors, mRNA transcripts and SYNGAP1; and more

Explore more from The Transmitter

‘Unprecedented’ dorsal root ganglion atlas captures 22 types of human sensory neurons

Not playing around: Why neuroscience needs toy models