Adult intervention

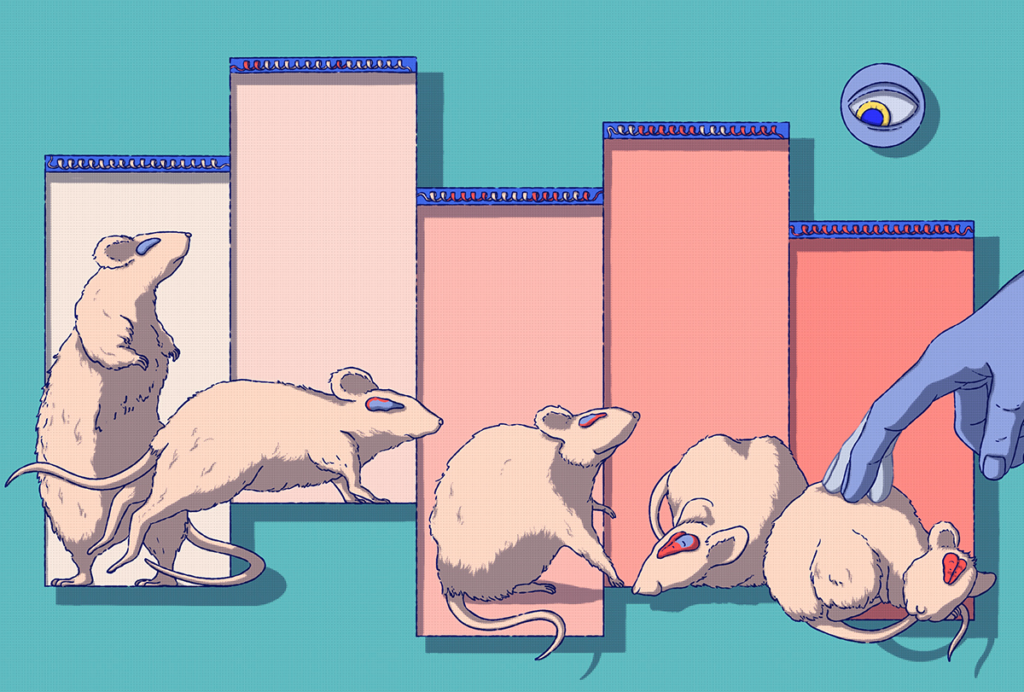

A new meta-analysis shows that less than two percent of participants in studies of behavioral interventions for autism are adults.

Behavioral therapy can have a profound effect on children with autism, and the earlier it is started the better. But how effective is it in adults?

The answer is a mystery. A new meta-analysis shows a severe paucity of research into interventions for people age 20 or older.

Analyzing 148 studies of interventions for autism from four journals — Autism, Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders and Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders — researchers found that the average age of participants ranged from 4 to 8 years old. Only 1.7 percent of participants were aged 20 or older.

The researchers point out that the study has limitations; it analyzes data from only four journals, for example. But the findings do fall in line with previous estimates, which suggest that adults with autism receive almost no behavioral therapy.

In general, very little is known about the course of autism in adults, though that is starting to change. More studies are following children into adulthood, or trying to recruit adults with autism, in order to better understand the evolution of the disorder.

Those studies highlight just how important it is to find effective therapies that can be used beyond childhood. As much as 75 percent of adults with autism are jobless, and even those with milder forms of the disorder are unlikely to marry or hold down jobs.

Fortunately, the research community is starting to recognize the problem. Last fall, the Autism-in-Older-Adults Working Group outlined six research priorities. One of these is to study whether drug treatments and behavioral interventions have the same benefits in children and adults.

Early research suggests there could be a big difference. Drugs can have different effects depending on age, and a study published in December found that Prozac, which has no benefit in children with autism, improves some symptoms in adults.

Assessing the effectiveness of behavioral interventions, such as efforts to teach social skills, in adults is a good first step, but common sense suggests that adults will need therapies specially tailored to their needs. And that will require research. Let’s hope that analyses such as this one will draw attention to the current dearth and attract more researchers into this area.

Recommended reading

Sex bias in autism drops as age at diagnosis rises

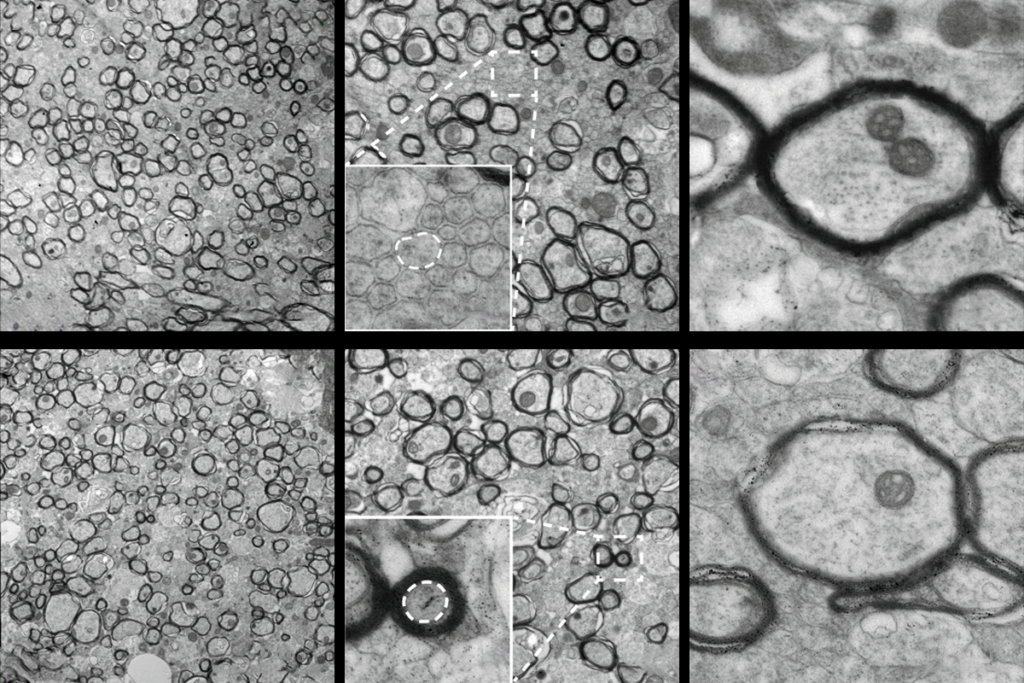

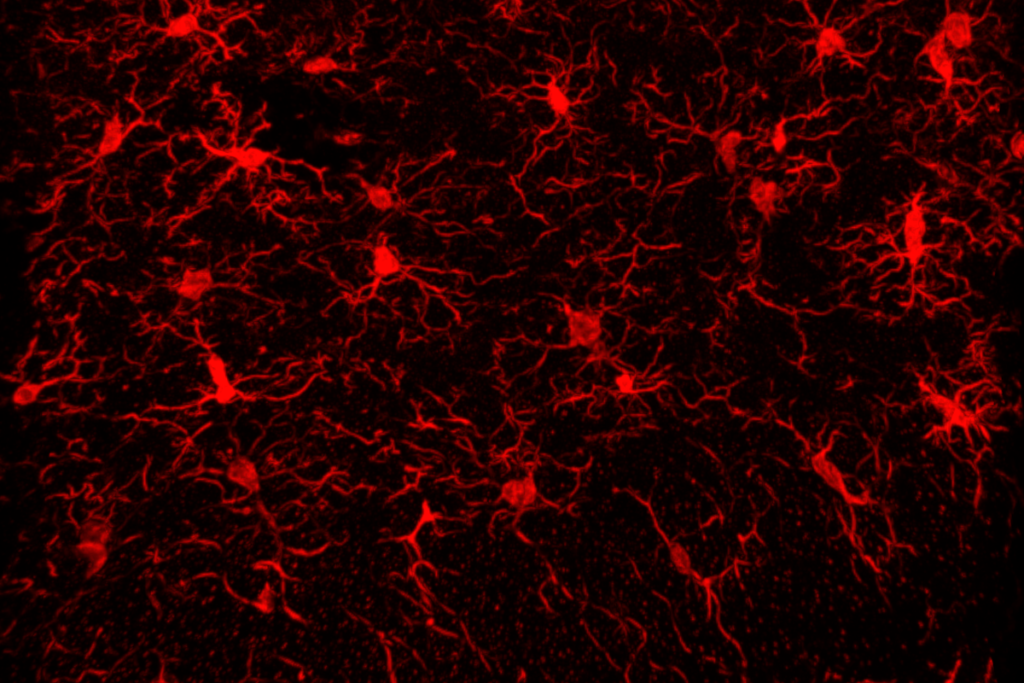

Microglia implicated in infantile amnesia

Explore more from The Transmitter

This paper changed my life: Ishmail Abdus-Saboor on balancing the study of pain and pleasure