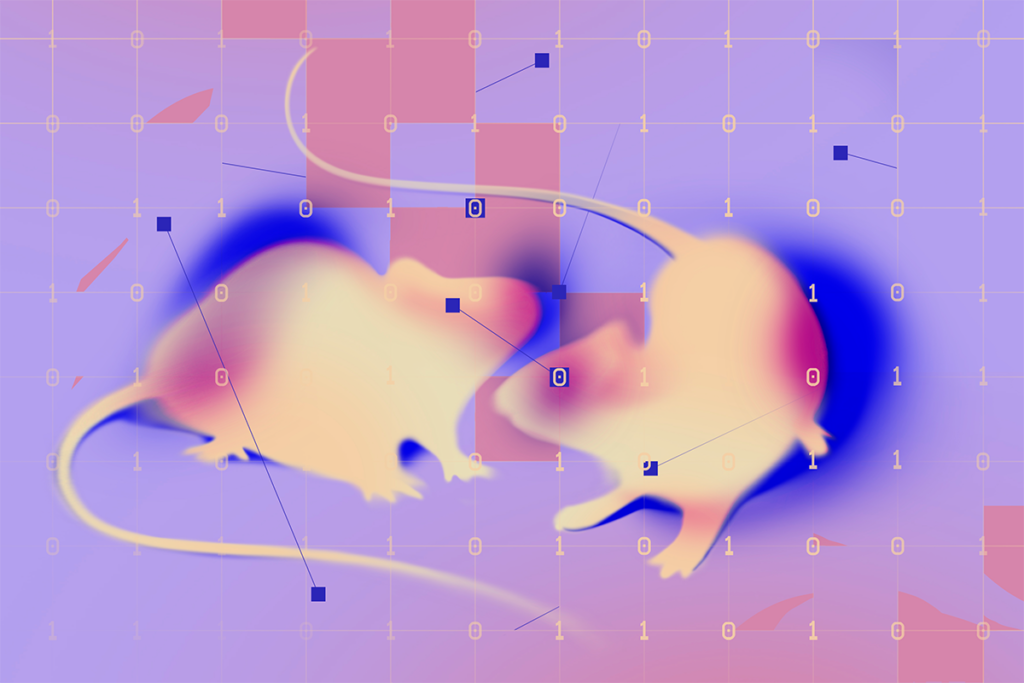

Many traits linked to Angelman syndrome appear to have a narrow treatment window. Candidate drugs that address the autism-linked condition’s genetic roots can alleviate epilepsy and anxiety-like and repetitive behaviors only when model mice are treated just after birth — roughly equivalent to third-trimester human fetuses — raising questions about how much this type of therapeutic stands to benefit children.

New work, however, offers hope that other traits may have a broader treatment window: Small molecules called antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), the same form of treatment under development for people with Angelman syndrome, improve sleep and normalize electroencephalography (EEG) signals in model mice beyond infancy.

Ongoing clinical trials are evaluating sleep and EEG changes in people with Angelman syndrome, but no study had tested whether these traits are amenable to treatment in adult animals, says lead researcher Mingshan Xue, assistant professor of neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. “We wanted to see if other aspects of this disease could potentially be reversed” later in life, he says.

“It’s really important work,” says Michael Sidorov, assistant professor at the Center for Neuroscience Research at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C., who was not involved in the study. “It suggests that there’s likely to be some benefit to starting a treatment” in people even at older ages, he says.

A

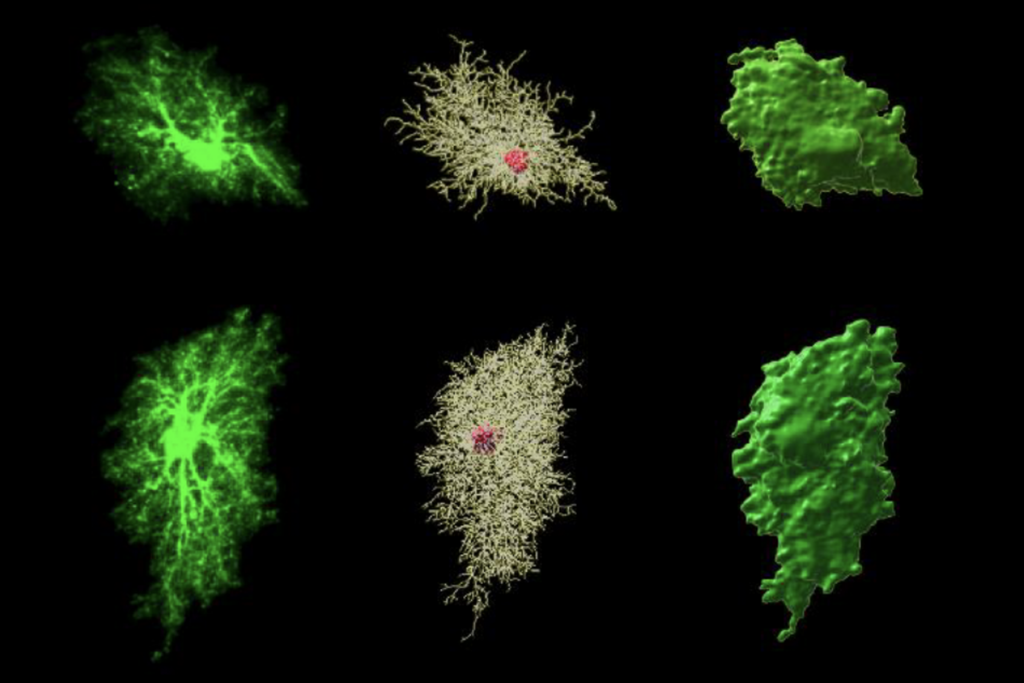

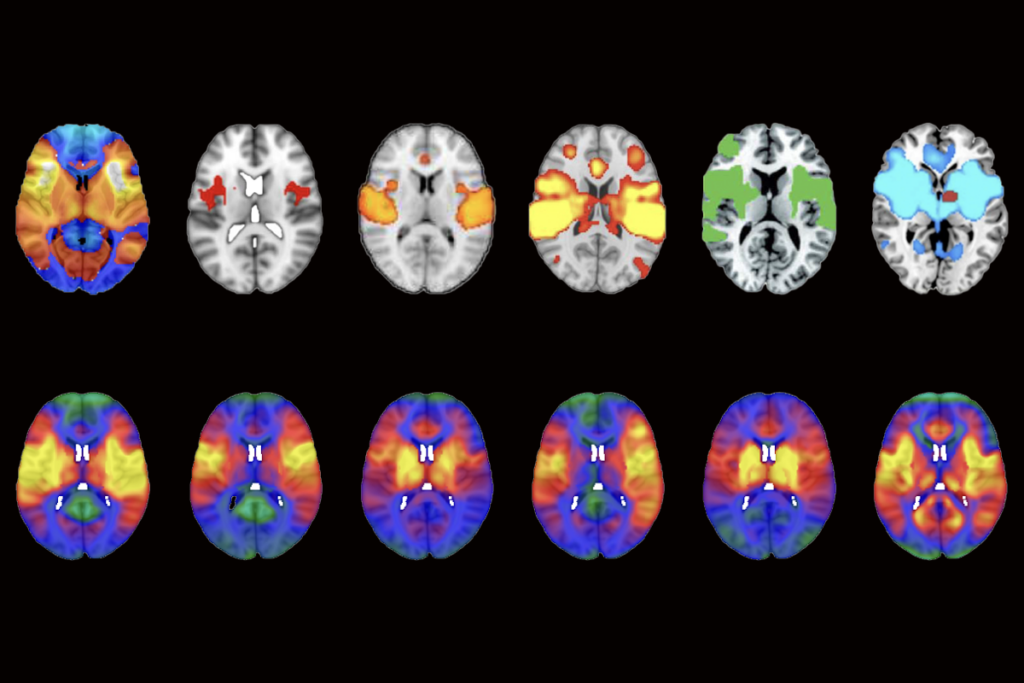

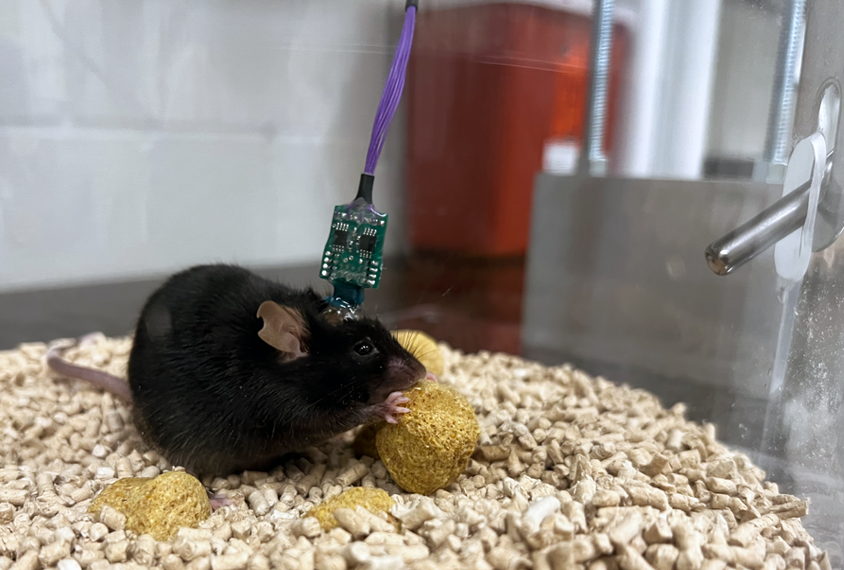

ngelman syndrome results from a mutated or missing maternal copy of the gene UBE3A, which can lead to traits such as developmental delay, motor difficulties, seizures, poor sleep and autism. A handful of companies have designed ASOs that aim to improve some of those traits by turning on the typically silent paternal copy of the gene.Xue and his colleagues injected one of two UBE3A ASOs — which target different regions of the gene’s antisense transcript for unsilencing — or a sham ASO into 3-week-old juvenile mice and 8-week-old adult mice. About a week later, the team implanted EEG electrodes in the frontal, somatosensory and visual areas of the animals’ brains for recording at three later time points.

Compared with sham-treated wildtype mice, sham-treated Angelman syndrome model mice have a higher intensity of brain waves in low-frequency bands relative to high-frequency ones, Xue and his colleagues found. But after treatment at either age, the relative intensity of waves in the Angelman mice more closely resembled that of wildtype mice.

Sham-treated Angelman syndrome model mice spent less time in the rapid eye movement (REM) period of sleep than did their ASO-treated wildtype counterparts, the new work also shows. Treating the Angelman mice with an ASO as juveniles increased their time in REM sleep to typical levels. The findings were published last month in eLife.

Higher levels of UBE3A protein expression throughout an animal’s brain correlated with larger changes in the EEG power ratio and time spent in REM sleep, suggesting that the treatment is responsible for the changes, says study investigator Wu Chen, instructor in neuroscience at Baylor College of Medicine.

The treatment did not normalize the animals’ brain hyperactivity, which is similar to the seizures seen in people with Angelman syndrome. That could mean that this trait, the poor sleep and the atypical brain rhythms are “mediated by different mechanisms” and thus require different treatment windows, the targeting of different brain areas, or different levels of UBE3A for improvement, Xue says.

T

he results, the team says, hint that boosting UBE3A well past infancy could still lead to large and potentially life-changing improvements in sleep for people with Angelman syndrome — a big concern for families, researchers and clinicians.It’s also possible that increasing UBE3A leads to cognitive improvements, too, Xue says. Cognitive ability correlates with the level of atypical low-frequency brain activity seen in people with Angelman syndrome, a 2021 study found, so an ASO that corrects those rhythms might improve other aspects of brain function. The team was unable to test that relationship in their study because Angelman model mice do not recapitulate the cognitive impairment seen in people with the condition, Xue says.

Whether the treatment pans out in people remains to be seen.

“I hope the EEG changes predict cognitive changes, but we’re going to need data to know that,” says Elizabeth Berry-Kravis, professor of pediatrics, neurological sciences, and anatomy and cell biology at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago, Illinois, who was not involved in the study.

Berry-Kravis is leading multiple clinical trials of ASOs for Angelman syndrome and says that the mouse findings support the improved sleep and normalized EEG signals suggested by interim data from those trials. But much is still unknown, she adds, including how reinstating UBE3A shapes later development.

“We don’t know what the timeframe of a treatment like this is going to be,” Berry-Kravis says. “We’ve never corrected a genetic cognitive disorder before.”