Adapted from “The Carriers: What the Fragile X Gene Reveals About Family, Heredity, and Scientific Discovery” by Anne Skomorowsky, scheduled to be published by Columbia University Press in May 2022.

Margaret* was 46 years old when we spoke for hours by phone. Randi Hagerman, medical director of the MIND Institute at the University of California, Davis, had suggested that Margaret would be interesting to interview because she provided an example of the broad autism phenotype (BAP), a set of personal traits that might be called a hint or whisper of autism. Originally recognized in some parents of children with autism, BAP doesn’t constitute a diagnosis. It’s more of a clinician’s impression.

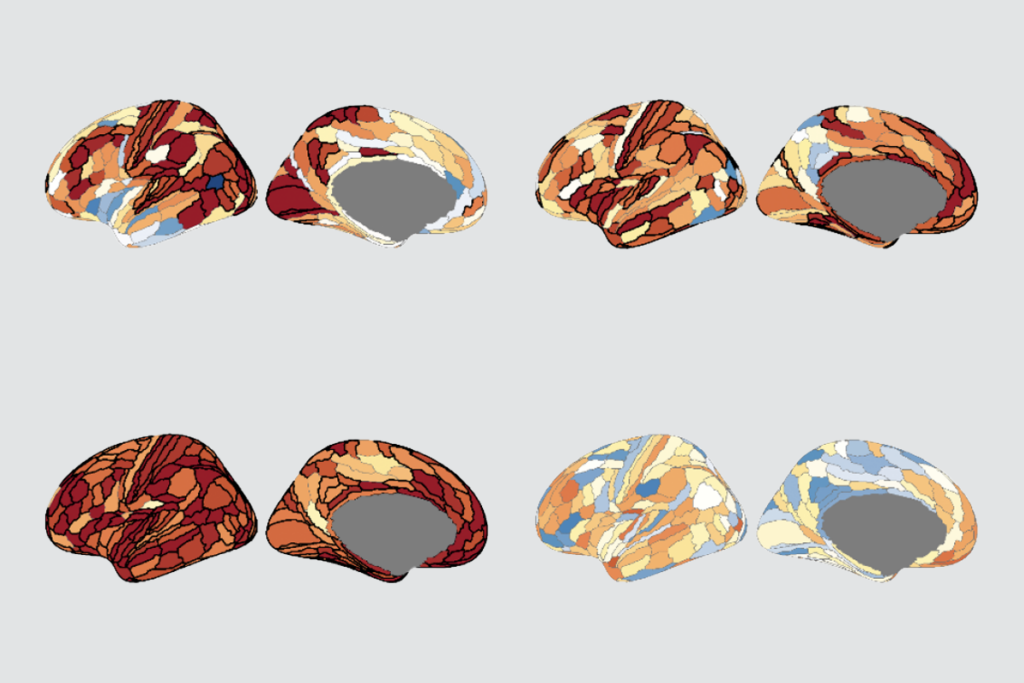

BAP is sometimes described as an endophenotype, because it combines observable characteristics (‘pheno-’ means showing or appearing) with inherent, biological traits (‘endo-’ means internal or inside). Geneticists like endophenotypes — also called intermediate phenotypes — because they are thought to reflect underlying genetic predispositions. So a mother of an autistic child might not herself be autistic, but investigation of her genome might reveal variant genes that she has in common with her autistic child. Such a discovery can help geneticists home in on genes of interest.

Molly Losh, an autism specialist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and her colleagues summed up what was known about the so-called BAP in a 2008 article in the American Journal of Medical Genetics B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics:

Converging evidence from a number of … studies indicates that certain personality traits and social behaviors are observed more commonly among autism relatives than control relatives of individuals with Down syndrome. … Both family history and direct assessment studies have reported elevated rates of socially reticent, or aloof personalities among autism parents, as well as untactful behavior, and fewer high-quality (i.e., emotionally reciprocal) friendships. Autism relatives have also been reported to more commonly display rigid personalities, showing relatively little interest in novelty or difficulty in adjusting to change in environment and activities, as well as perfectionistic or overly conscientious, detail-oriented traits. Finally, anxiety-related features … also appear more common among parents of individuals with autism. These characteristics closely correspond to the social impairments, ritualistic/repetitive and anxious behaviors observed in autism, making them good candidates as autism intermediate phenotypes.

Hagerman had treated Margaret’s son, Joseph*, for fragile X syndrome with autism traits. Over the course of the treatment, she had come to know and become quite fond of Margaret. Hagerman’s clearest memory of Margaret is the repeated phone calls Margaret made to her during the early years after Joseph’s diagnosis. Mothers of her fragile X patients are often eager to talk to Hagerman, but Margaret was particularly relentless, asking the same questions over and over, almost begging at times for reassurance that her son would be OK.

Margaret was very helpful to me, tolerating a lengthy interview and sharing her life history unsparingly. But “untactful,” “rigid” and “hypersensitive” — Molly Losh’s terms — seem to me to be accurate descriptions, and I think that Margaret would acknowledge them.

She describes an isolated childhood, with depression and eating disorders as far back as she can remember. She had no friends and was bullied. Her interests were, and still are, solitary: reading, knitting, libraries. She told me, “I’m depressed; I’m not normal; I was weird in school. I would do what anyone wants if I would meet a man.” That last sentence reflects what executive-function researchers call impulsivity, and BAP researchers call “lack of tact” — a failure to inhibit a conversation-grabbing digression.

Margaret was hospitalized twice with bulimia as a teenager. She described driving around her hometown alone, binging and purging in the car. “I had severe depression, always, problems getting along with people, choosing bad men, in very abusive relationships, bad choices. I don’t feel good about myself. Whatever I do, it doesn’t work out.”

She found out she was a carrier of fragile X syndrome when Joseph was diagnosed. As a carrier, she has an alteration in a gene on the X chromosome that codes for fragile X messenger ribonucleoprotein 1 (FMR1). Carriers have what is known as a ‘premutation’ — excessive repetition of the nucleotide sequence cytosine-guanine-guanine (CGG) in this gene. That expansion is insufficient to cause full-blown fragile X syndrome, but it makes the gene unstable and prone to expand further in subsequent generations, as it did in Joseph’s case, causing the full syndrome. Many carriers are unaffected by the altered gene, but others have a variety of health and cognitive issues.

It’s apparent when speaking with Margaret that she is very intelligent but has difficulty expressing her thoughts appropriately. This trait is consistent with BAP but is also characteristic of some people with the premutation. Many researchers have shown that symptomatic premutation carriers tend to have deficits in executive function — the aspects of cognition that involve planning, setting priorities, processing feedback and staying on task. Margaret’s behavior from her youth to her current age is rife with executive dysfunction. But this impairment is also visible in how she tells a story: full of non sequiturs, repetition, oversharing and an inability to judge how she is being heard.

Some researchers divide BAP-related difficulties with pragmatic language into two camps. People who control conversations and are excessively verbose have a “dominating” style, described in a 2012 paper by Losh and her colleagues as “overly detailed, vague, tangential, overly frank, pedantic, overly talkative, no reciprocation, topic preoccupations and interruptions.” This surely applies to Margaret. Those with a “withdrawn” style offer too little information and require much prompting.

Even infant girls who carry the premutation and are too young to speak can display behavioral, gestural elements of BAP. In one 2016 study, premutation carrier babies had fewer gestures than average and poorer eye contact. The researchers write: “These results suggest that infants with a premutation may present with subtle developmental differences as young as 12 months of age that may be early markers of later anxiety, social deficits or other challenges thought to be experienced by a subset of carriers.”

Why bother with BAP?:

About 14 percent of boys with the premutation meet the criteria for autism, and about 5 percent of girls do. But the premutation-related endophenotype — the hint of autism, sometimes evident from birth — may be far more common.

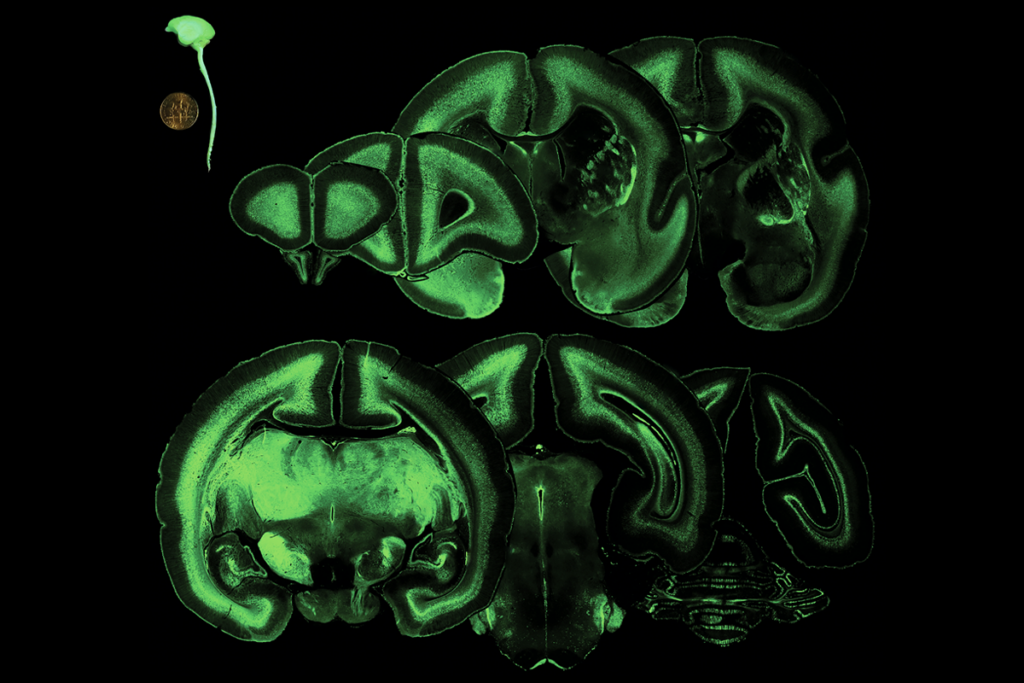

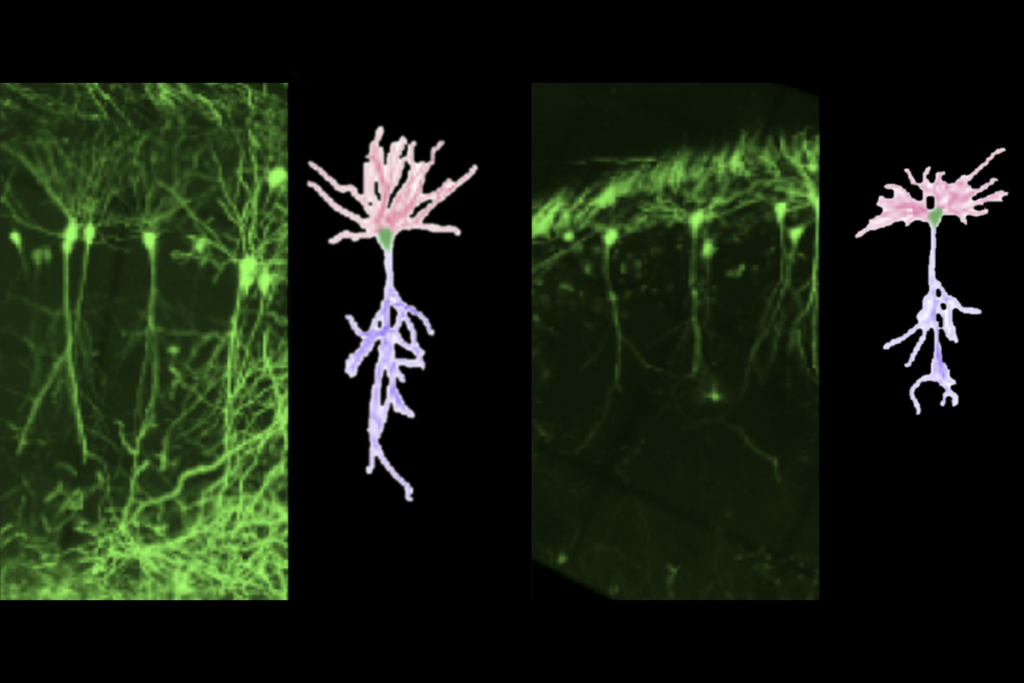

So why should anyone care about BAP, which is not even considered a diagnosis but more of an unusual personality style? Because the premutation carrier’s susceptibility to BAP may shed light on the cause of idiopathic autism, or autism of unknown cause. FMR1 mutations are the most prevalent known single-gene cause of autism and the most common inherited cause of intellectual disability. That means that investigating premutations of this gene can help researchers home in on the high-support forms of autism found in many people with a full mutation. When we know precisely what alterations in FMR1 do in the brain, we will understand at least one relatively common cause of autism, and with luck we can extrapolate it to others.

This relationship is far from completely understood, but it seems that the FMR1 protein, FMRP, which is absent in people with fragile X syndrome and poorly regulated in those with the premutation, interacts with more than 100 different genes suspected to be involved with autism.

Thus, FMR1 has an effect on multiple genes that may lie behind the complex genetic disorder that is autism. Abnormalities in FMR1 production and in associated messenger RNA could constitute some of the many ‘hits’ that are hypothesized to be responsible for autism of unknown cause.

Stuck in the middle:

Research has shown that although many male premutation carriers have subtle autism traits, female carriers are more prone to obsessive-compulsive tendencies and anxiety. Because all men with premutations pass their X chromosomes and premutations to all of their daughters, this leads to a recurring situation in carriers: that of a young girl who is anxious and obsessional being raised by a father who is rigid, perfectionistic, has limited interests and is often of a solitary nature — in other words, a father with BAP. That describes several female carriers I have interviewed, including Mara.*

When Mara was just 25, before she considered having children, she saw a gynecologist to evaluate her chronic pelvic pain. The pain was so bad that after walking around for several hours while working the night shift at a cable news station, she could barely stand. During this same period, Mara began to notice that her father, Stefan, was struggling with his own health challenges. He had developed a tremor and was having trouble getting up from a chair. A neurologist had diagnosed him with Parkinson’s disease, but now we know better: Stefan had fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS), a movement and gait disorder that often occurs in older carriers. Mara’s pelvic pain was eventually diagnosed as another condition associated with the premutation: fragile-X-related ovarian primary insufficiency (FXPOI), which can cause infertility and premature menopause.

Stefan had retired from a career as a certified public accountant. His hobby was rocketry. His greatest pleasure, Mara told me, was blowing things up. As a much younger man, he was prone to road rage and did not seem to care that his reckless driving put his children in danger. He hardly played with his children, although he would take them along on rocket launches and to hobby stores, often lecturing them on technique. He never joked and rarely laughed. When I asked Mara if she had ever wondered if he was on the autism spectrum, she said she had. When I asked her if she had ever wondered if she was on the autism spectrum, she said no: “I think it’s more that I was raised to think nothing I ever did was good enough. Now I can’t look anyone in the eye because I am so unsure of myself.”

At the time of this writing, Mara, now 42, has been lucky enough despite FXPOI to have two sons: Tommy, 12, and Matt, 14, each of whom also carries a premutation. Her boys are what Hagerman calls “high-level” premutation carriers, with 180 and 166 CGG repeats respectively — just short of the 200 or more repeats that cause fragile X syndrome. Hagerman says that such carriers experience a double hit: They have traits related to toxic mRNA from their expanded CGG lengths, and they are likely to have low FMRP levels compared with children who have fewer repeats. Neither boy is intellectually disabled, but both struggle with mental health and behavioral problems. “I love my sons,” Mara told me. “But this has been hell.”

Tommy, whose challenges are more obvious, according to Mara, has been diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and mood instability. He is anxious and has a phobia of pigeons. Crowds, smells and loud sounds upset him, and he has poor coordination, including difficulty writing. He is good-natured but very vigilant. “He talks all the time, runs ahead of everyone else in the group — it can be hard to take,” Mara said. “Matt beats the shit out of him, because it drives him crazy.” Tommy takes clomipramine, an older antidepressant, for his phobia, and guanfacine, or Intuniv, and methylphenidate, or Ritalin, for ADHD. He takes aripiprazole, marketed as Abilify, to stabilize his mood.

Tommy’s speech is unusual. He stays on a subject too long, and he occasionally uses the third person inappropriately or resorts to baby talk. His speech is cluttered with words that bunch together, and he often leaves out a letter or a word. These are examples of ‘pragmatic language violations’ — pragmatic referring to how language is used in conversation. Tommy doesn’t look people in the eye, and he talks to himself. Although more than one psychiatrist has told Mara that Tommy does not meet the criteria for autism, in my view, he surely meets the criteria for BAP.

Matt has been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. He had his first manic episode around age 11, when his pediatrician started him on sertraline (Zoloft) to treat his anxiety. He became sexually preoccupied, got knives out from the kitchen and carried them around, and beat his little brother with a rod. He told his mother, “I’m having violent thoughts, but I don’t want to kill anybody.” Now he takes the same three medications as his brother, plus venlafaxine (Effexor) and sodium valproate (Depakote).

Mara’s family is a classic three-generation fragile X family — three generations of premutation. The grandfather, now with FXTAS, previously with BAP, was withholding, humorless and disapproving to his children. Mara internalized his disrespect for her, and that, combined with a premutation woman’s tendency toward mood and anxiety disorders, led her to dislike herself and, at times, her sons. Meanwhile, the boys, with their high-level premutations, are intellectually intact, but Tommy in particular has many social behaviors common to both fragile X syndrome and autism.

What it means to be ‘typical:’

A hint of a condition — a pattern such as BAP — shines a light on what it means to be neurotypical and what constitutes an actual condition. A boy like Tommy is, in his mother’s words, “obviously strange” in terms of his behavior and language. But Tommy doesn’t have autism; he has BAP.

Thinking about the ‘neurotypical’ person and neuropsychiatric conditions got me curious about myself. You can’t spend years researching a condition whose symptoms can include everything from anxiety to dementia to nothing and not wonder where you fall on the spectrum of risk.

Hagerman had been after me for years to get tested for the premutation because of my own medical history. I thought it quite possible that I was a carrier. I’m an anxious person, and I had autoimmune thyroid disease, which is common among carriers. My periods had stopped a few years short of the U.S. average. And as my father aged into his 80s, he developed a tremor and sometimes fell when he tried to sit down. Maybe he had FXTAS.

I finally decided to get tested after I learned I needed a pacemaker to adjust my slow heart rate — another symptom sometimes found in carriers. I pondered what I would tell my daughters if it turned out that I was a premutation carrier. But that turned out not to be the case. Testing showed that I had two FMR1 alleles, like all neurotypical women. Both had 29 CGG repeats — not too many, not too few.

My heart rate had slowed because of something called sick sinus syndrome, which means that something was wrong with the pace-setting sinus node of my heart. My period stopped in my late 40s because, well, it just did. And I had thyroid disease because thyroid disease is common. And anxiety? Don’t we all have that, at least some of the time? As a doctor, I know that when you hear hoofbeats, you should think of horses, not zebras.

So none of those problems had anything to do with an FMR1 mutation, right? But once your eyes have been opened to what a “silent” mutation can do, it keeps you wondering. Maybe my health problems, or even my character, had to do with some as-yet unnoticed mutation, another bit of underappreciated DNA. To me, this relieving result only adds to the mystery of the premutation. How many others are out there, waiting to be discovered?

* Margaret is a pseudonym, as are the names of other individuals in this excerpt. Some of their personal details have been changed for anonymity and clarity.

Skomorowsky is clinical instructor in psychiatry at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and an attending psychiatrist at NYU Langone Hospital. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, Scientific American and Slate.